The Moving Poem "About Poland Erased from All the World’s Maps," Sung by Japanese Students and the Imperial Japanese Army

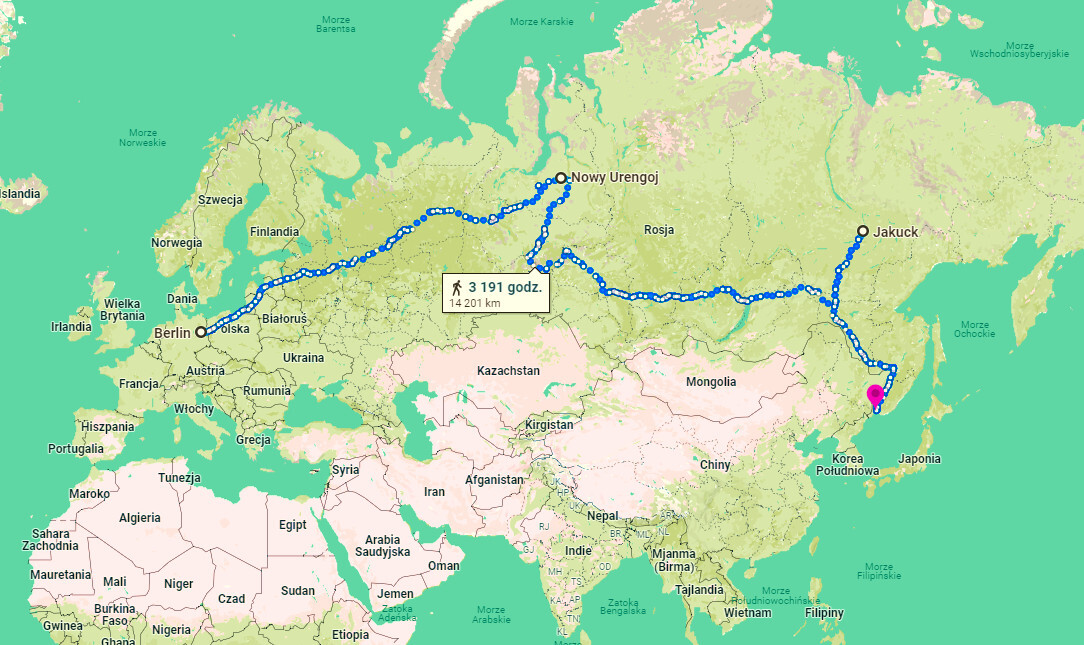

15,000 km on Horseback

Imagine a journey on horseback from Berlin to Vladivostok—over 15,000 kilometers, nearly half the globe. Does it sound like a wild adventure from a novel? Yet, this is the true story of Yasumasa Fukushima, an officer of the Imperial Japanese Army, who undertook this journey alone in 1892–1893. Moreover, during this epic journey, Fukushima became the first known Japanese person in history to visit Polish lands.

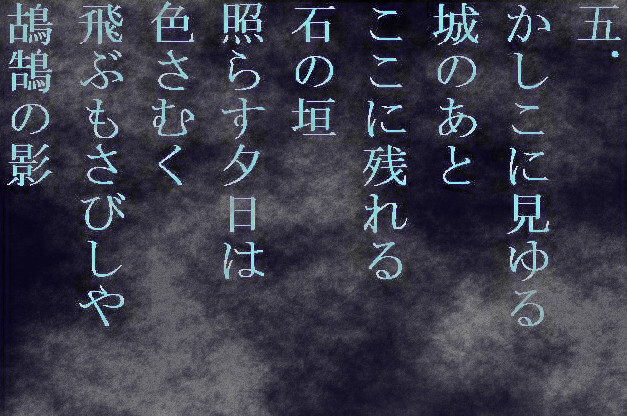

Traveling through Polish cities and villages, Fukushima witnessed both the ruins of former grandeur and the unyielding spirit of a nation. These impressions were immortalized by Japanese poet Ochiai Naobumi in the poem "Porando Kaiko" (波蘭懐古 - "Remembrance of Poland"), which quickly gained immense popularity in Japan. Here is an excerpt:

さびしき里にいでたれば

ここはいづことたづねしに

聞くもあはれやそのむかし

亡ぼされたる波蘭

"When I finally found a village, gray and desolate,

I asked, where am I, and what is this land called?

Overwhelmed with compassion, I listened to stories of old,

About Poland, erased from all the world’s maps."

(Translated to Polish by Agnieszka Żuławska-Umeda)

Fukushima’s story is not only one of courage but also of a fascinating encounter between two very different cultures, which over the past century have become surprisingly close and friendly. Let us now explore how Fukushima managed to ride those 15,000 kilometers on horseback!

Japan and Poland in the Second Half of the 19th Century

Japan in the Meiji Era

Poland under Occupation

In cities like Warsaw and Kraków, people dreamed of freedom, reading forbidden books and attending secret gatherings. In the countryside, echoes of stories about the country’s past glory—when Poland was a European power—resonated. On the faraway steppes of Siberia, Poles continued to be exiled for speaking out against the Tsar, and their stories inspired others. It was a time of heroic struggle to preserve the Polish national identity—from uprisings to daily resistance against Russification.

These two stories—of Japan and Poland—ultimately intertwined, even though they seemed worlds apart in culture, geography, and history. Yet, in their hearts beat the same rhythm—a rhythm of nations fighting for their place in the world. Traveling from Berlin through Poland to Vladivostok, Yasumasa Fukushima became a witness to this incredible tale.

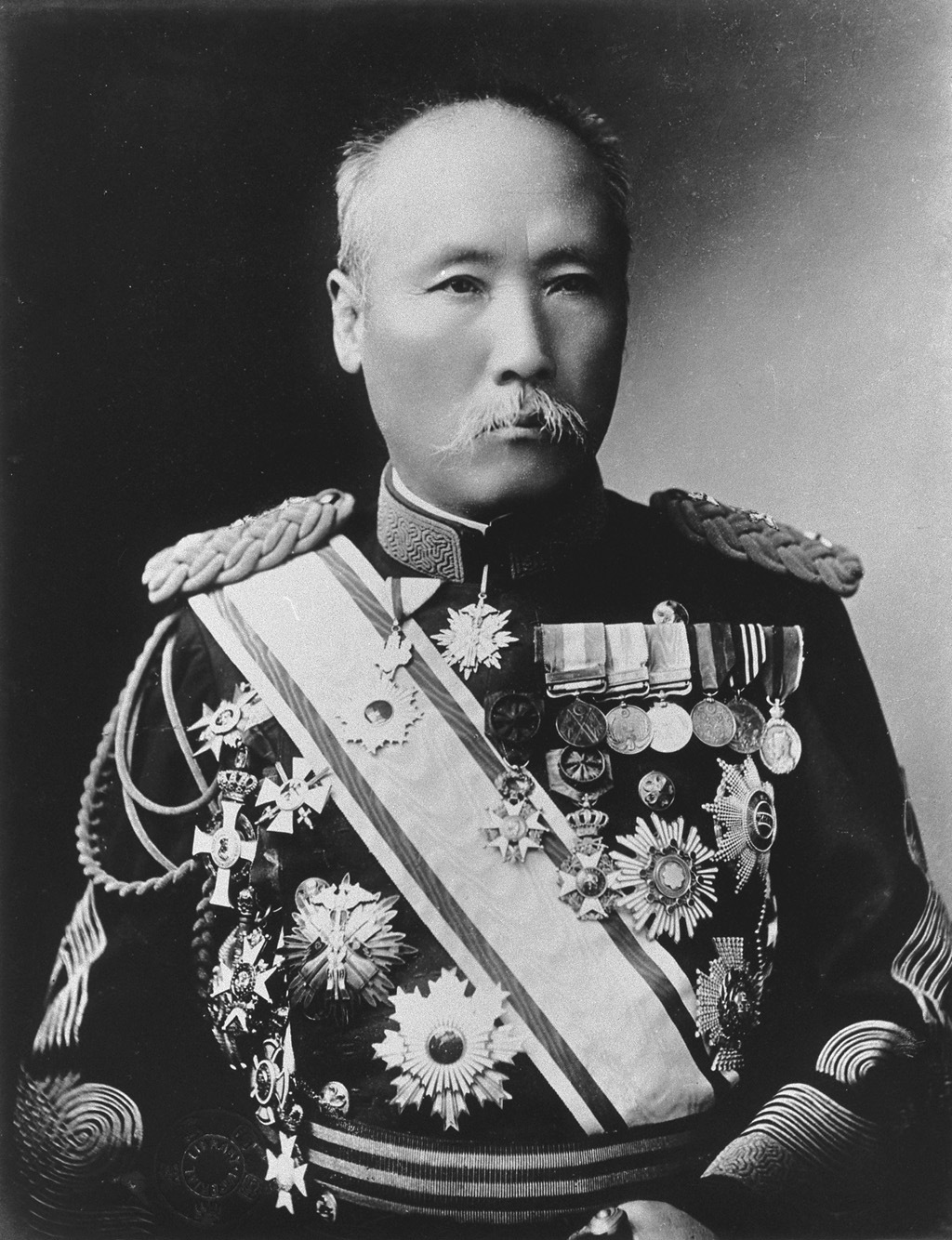

The Story of Yasumasa Fukushima

Origins

Even as a child, he displayed remarkable abilities—quickly absorbing knowledge, with a passion for foreign languages. At the age of just 15, he went to Edo (modern-day Tokyo) to train at Kobusho, a prestigious military academy. There, he learned not only military tactics but also Western combat techniques, which were soon to dominate modern armies. This was the moment when young Fukushima realized that Japan’s future demanded change, and he resolved to become an instrument of that transformation.

The Warrior and the Spy

Fukushima’s first major missions took place in Mongolia and China. Disguised as a traveler, he mingled with local populations, studied their attitudes toward Japan, and sought potential allies. After returning, he compiled detailed reports that laid the groundwork for further Japanese intelligence operations in the region.

A National Hero of Japan

After returning to Japan in 1893, Fukushima became a national hero. His journey was hailed as a feat worthy of the samurai spirit, and Emperor Meiji personally awarded him the Order of the Sacred Treasure, Third Class. The press portrayed him as a model of Japanese perseverance and bravery, and schoolchildren learned about his achievements as an inspiration to serve their country.

Throughout his life, Fukushima embodied both the old and new worlds. He was a samurai at heart, yet also a symbol of modern Japan boldly confronting the challenges of global politics. His life is a story of determination, honor, and an insatiable curiosity about the world.

The Epic Journey of Yasumasa Fukushima

February 1892—In the cold, industrial air of Berlin, the rhythm of Europe’s modernization is palpable. Amid the crowd bustling beneath the towering facades of the German capital stands a man in a military coat, holding the reins of his horse. This is Yasumasa Fukushima, an officer of the Imperial Japanese Army, ready to embark on a journey that will go down in history. His destination: Vladivostok, a distant port at the eastern edge of Russia, nearly 15,000 kilometers away. Although officially described as a geographic and ethnographic expedition, in reality, this was a covert intelligence mission to assess Russian infrastructure and military preparations.

To the public, Fukushima’s expedition was portrayed as a romantic traveler’s adventure. The officer himself described it as “research-oriented”—to observe the customs of Asian peoples, document landscapes, and record interpersonal relations. But the truth was far different. Fukushima had one goal: gathering intelligence for the Japanese General Staff. Russia, Japan’s neighbor, was seen as its primary rival, and the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway posed a strategic threat. Fukushima was tasked with assessing the progress of the railway, evaluating conditions for troop transport, and collecting data on Russian garrisons.

On February 11, 1892, Fukushima set out from Berlin. His route took him through Prussia, Poland, Russia, and Siberia, all the way to Vladivostok. Traveling on horseback, occasionally changing mounts along the way, he embarked on a challenging journey. Imagine the scene: a lone rider traversing snow-covered fields, small villages, and vast, boundless plains. Each day presented new challenges—frost, exhaustion, and the suspicion of locals toward the exotic traveler. The entire journey lasted 487 days.

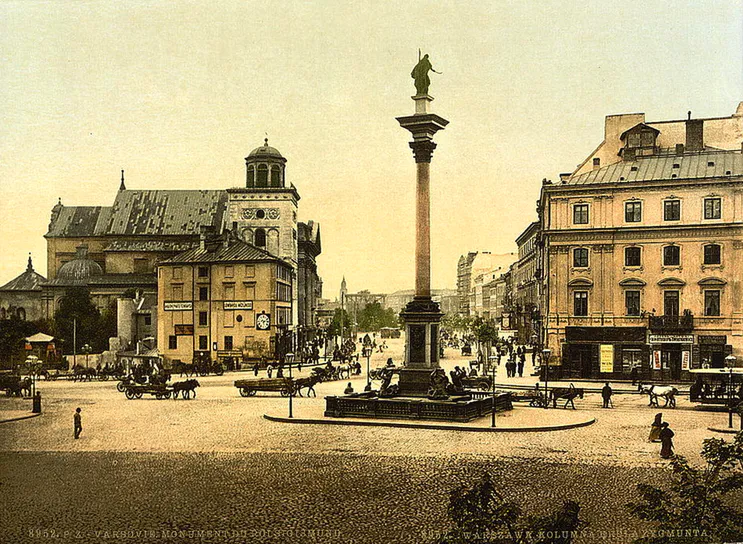

On Polish soil, still under partition, Fukushima traveled through Warsaw, Łowicz, Kutno, and Suwałki. Polish villages and neglected castle ruins that he encountered along the way reminded him of desolate landscapes from stories of fallen powers. He often asked locals about their lives and political situation. His experiences and reflections from this time later inspired the verses of the poem Porando Kaiko.

After leaving Polish lands, Fukushima entered the vast territories of the Russian Empire. He passed through cities like St. Petersburg and Moscow, observing the daily lives of residents, the opulence of the Tsar’s courts, and the harsh conditions of life in the provinces. Russian military garrisons were of particular interest to him—he studied the number of soldiers, the state of their equipment, and potential troop movement routes.

As his journey continued eastward, the landscape grew increasingly harsh. Siberian taiga, icy rivers, and snow-covered hills tested his endurance. One day, his horse collapsed from exhaustion—Fukushima had to purchase a new steed from a local trader. Imagine a winter night in Siberia: stars in the sky, snow crunching beneath the horse’s hooves, and a silence so profound it was almost painful.

After nearly a year and a half in the saddle, in June 1893, Fukushima reached Vladivostok. There, his expedition came to an end. The horse that accompanied him during the final stages of his journey was transported to Tokyo and became an attraction at the local zoo. The mission was a success: Fukushima delivered reports that enriched Japanese military strategies and cemented his status as a national hero.

A Stay in Poland: The First Japanese on Polish Soil

It was February 1892 when Yasumasa Fukushima, on his resilient horse, crossed the border of the Russian partition and entered the lands of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. At that time, Poles lived under the yoke of three great powers—the partitioners who had erased the Commonwealth from the world map. Fukushima’s presence, though likely unassuming at the time, carried symbolic weight—he was the first known Japanese person in history to set foot on Polish soil.

Although detailed accounts of Fukushima’s encounters with Polish independence activists have not survived, it is possible that he had conversations aimed at exchanging information. Exiles who had returned from Siberia, or their descendants, were valuable repositories of knowledge about Russia—its administration, army, and social sentiments. Known for his ability to establish connections, Fukushima could have gathered from Poles crucial data that was later utilized in his reports for the Japanese General Staff.

Warsaw: The main city of the Russian partition, full of contrasts—Russian troops on the streets, but also Polish intelligentsia secretly nurturing national culture. Fukushima might have witnessed both the opulence of Tsarist officials and the poverty of working-class districts.

Łowicz and Kutno: Small towns where remnants of the former Commonwealth were visible, such as old churches and the ruins of noble manors. Fukushima described these places as filled with melancholy and sorrow, sentiments later captured by Ochiai Naobumi in his poem.

Suwałki and Augustów: Borderlands where the winter landscapes of Siberia seemed to begin long before its actual border. Snow-covered roads and isolated homesteads must have made a strong impression on him.

During his journey, Fukushima had the opportunity to meet Poles from various social classes. Particularly intriguing were his conversations with exiles or their descendants, who, like him, had traveled across the vast expanse of Russia. These individuals often provided insights into social sentiments in the Russian Empire and the realities of life under partition.

It is said that Fukushima was not only a spy but also a keen listener—though perhaps one quality stemmed from the other. During his conversations with Poles, he likely learned of their suffering and their hopes for freedom. Such stories may have inspired Ochiai Naobumi to write Porando Kaiko.

As he traveled through Poland, Fukushima not only collected data but also experienced profound personal reflections. It was here, on these lands erased from the world’s maps, that he came to understand the importance of preserving national identity. The Poles he met left a lasting impression on him—one that later inspired the beautiful Japanese poem about Poland. For this reason, his journey through Poland was not just a geographical stage of his expedition but also a spiritual experience.

What Remained of Fukushima’s Visit to Poland?

The Poem Porando Kaiko by Ochiai Naobumi

Porando Kaiko reflects on how easily great powers can fall if they lose unity and internal strength. Poland, once a great kingdom, became for Naobumi a cautionary tale for Japan, which at the time was fighting for its position on the international stage.

The poem, though initially a literary reflection on Poland, gained universal meaning, addressing the transience of nations’ fortunes and the fragility of their greatness.

***

Pierwszego i drugiego dnia pogodne było niebo

A trzeci, czwarty, piąty dzień już tylko wiatr i deszcz

Błądzimy tak, mój koń i ja po kamienistych drogach

Górską percią, i lasem, i polem rozległym.

Mimo że śnieg nie pada, plecie się z zimą wiosna

I burze i wichury, jakże tę ziemię mrożą

Lody, skujcie ziemię białym jak dziś porankiem

Szrony niechaj pobielą tę dzisiejszą noc.

Przeszliśmy już, mój koń i ja, niemiecką wszerz krainę

I rosyjska granica za nami została

Tutaj mróz jest zwycięzcą, daje się nam we znaki

Nie masz już dnia bez gradu, codziennie pada śnieg

Gdym wreszcie znalazł wieś, szarą i posępną

Spytałem, gdzież zaszedł i jak zwie się kraj

Litością zdjęty dawnych słuchałem powieści

O Polsce startej z wszystkich świata map.

Tam widać ślady potężnego zamku

Tu mur obronny został z dawnych lat

Błyszczą się w ziemnym świetle słońca o zachodzie

Nawet kukła lecąca smutnym kreśli cień.

Zwykłe światu są chwała, zmierzch, rozkwit, upadek

Znana to kolej rzeczy i porządek życia

Ale aż takie zgliszcza i taką ruinę

Sam nie wiem, czy kto widział nawet w mroku snów.

Zwykłe świata pytanie być albo nie być, wznosić czy rujnować

Zasada, której nie zaprzeczy nikt

Trzeba tu być choć raz i zobaczyć

Tę ziemię, na której nie ma dla nieszczęścia granic.

Military Song

The song became part of the repertoire of Japanese schools and the military. Until 1942, it was a mandatory element of patriotic education, particularly in primary schools. Students recited the verses and learned about Poland’s history as a tragic example of a fallen nation. The song was also popular among soldiers, sung during marches and military ceremonies.

During World War II, the song began to be seen as too depressing and inconsistent with the need to foster optimism in difficult times. In 1942, it was officially banned by Japanese authorities, who deemed its sorrowful tone potentially demoralizing for soldiers. After the war, under American occupation, the song never returned to school curricula.

Impact on Japanese Education and Culture

During the Meiji era, Poland was seen as a nation that had lost its independence due to internal divisions and weaknesses. Japanese elites used this example to emphasize the importance of unity and strong state institutions. For many Japanese, Poland became a distant but fascinating example of a country with a rich history and culture that had to face a cruel fate.

Until 1942 (and in some cases until 1945), Porando Kaiko was taught in schools as part of literary and patriotic programs. Its verses were recited during school assemblies, and its melodies resonated in music lessons. However, after the war, in the new reality of American occupation, Japan’s education system was reformed, and military songs, including Porando Kaiko, were removed from the curriculum.

Although Porando Kaiko disappeared from official educational programs, it left a mark on the memory of the Japanese people. To this day, it serves as an example of how literature and art can connect nations, even when separated by thousands of kilometers.

The Modern Samurai

Fukushima’s journey from Berlin to Vladivostok was not only an act of extraordinary courage and perseverance but also a profoundly symbolic event. It demonstrated how forward-thinking and committed to modernization Japan was at the end of the 19th century. At the same time, Fukushima’s encounter with Poland—a nation of tragic history—inspired both Japanese literature and mutual understanding between the two cultures. This extraordinary expedition shows that even in times of division and tension, it was possible to build bridges between distant corners of the world.

Today, Yasumasa Fukushima and his journey are remembered in Japan as an example of determination and patriotism. In Poland, his visit and the Remembrance of Poland associated with it symbolize the extraordinary and unexpected relationships that have shaped the history of both nations. Yet it is painful to admit how little we, Poles, remember of the many stories that have linked our friendly nations over the past centuries.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Poles as Pioneers in Research on the People of Hokkaido – Ainu

Polish Children in Siberia: From Japanese to Polish Soil

Maurycy Beniowski: The Adventures of a Daring Pole in Edo Period Japan

'Go, Karolina!' - How a Polish Woman Conquered Japan

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!