Japanese children know "Hōjōki" by heart – but what can we learn from a monk of the 13th century?

A plan for life and a mobile home

In the European tradition, we also find echoes of similar thought. Memento mori reminds us of death, Heraclitus tells us one cannot step into the same river twice, and the Stoics train themselves in indifference toward what lies beyond their control. Yet Chōmei differs in a fundamental way: the European “remember death” is often a warning, a moral finger pointed toward the heavens. In Chōmei’s case, it is acceptance – not cold resignation, but a quiet reconciliation with the fact that the wave will take the house, the leaves will fall, and we will have to leave. Impermanence is not here merely an observation or conclusion – it is the center of gravity and the very heart of his ontology. In this logic, catastrophe does not contradict the order of the world; it merely exposes the illusion that such order was ever mankind’s possession.

The River

ゆく河の流れは絶えずして、しかももとの水にあらず。淀みに浮かぶうたかたは、かつ消えかつ結びて、久しくとどまりたるためしなし。

“The river flows on without ceasing, yet the water within it is never the same. The bubbles of foam floating on its surface, vanishing and forming anew, resemble human beings and their fates – appearing and disappearing, never lasting long.”

This image is deeply rooted in Japanese culture, where awareness of mujo (無常, impermanence) has shaped reflections on life for centuries. Chōmei does not describe abstract ideas; instead, he offers a sensory experience: the sight of the flowing river, its murmur, the play of light on its surface. This is an impression available to anyone – one need only stop at the bank and look. And yet, not all of us draw conclusions from this sight. Chōmei does: he reminds us that just as the current carries the water, so time carries us and everything we know.

In this, too, there is an echo of Buddhist mindfulness practice: a gaze fully present upon what is here and now, without the false belief in the eternity of forms. Hōjōki begins like a sudden enlightenment – as if someone had opened a window in a stuffy room and let in a breath of fresh air. Instead of a long introduction, we are given a strike at the very heart: the world changes, we change, and the only thing we can truly do is to see it clearly.

The difference lies in the fact that in Hōjōki, impermanence (無常) is not merely a cause for sorrow or a moral admonition – it is the core of cosmology and ethics, organically intertwined with the Buddhist vision of the world. Chōmei does not say, “remember that you will die,” but rather: “that which is impermanent is natural; harmony lies in accord with this rhythm.” In this way, his view, though universal in intuition, differs in tone and purpose from many Western approaches, which more often treat transience as a problem, a threat, or a loss, rather than as the fundamental order of things.

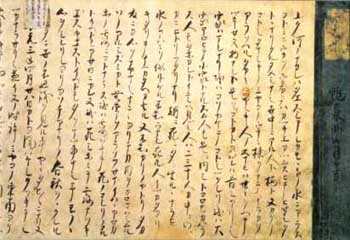

What is Hōjōki?

Hōjōki holds a special place in the history of Japanese literature, alongside works such as Makura no sōshi by Sei Shōnagon and Tsurezuregusa by Yoshida Kenkō. It belongs to the canon of classical texts that define Japan’s medieval aesthetics – a fusion of the elegance of a simple style, deep Buddhist reflection, and subtle observation of nature. Its influence reaches far beyond literature – it has inspired painting, theatre, and modern philosophical essays. Above all – it is one of the fundamental building blocks from which the Japanese worldview has been shaped – not only in the medieval period, but in all the centuries that followed, including the twenty-first.

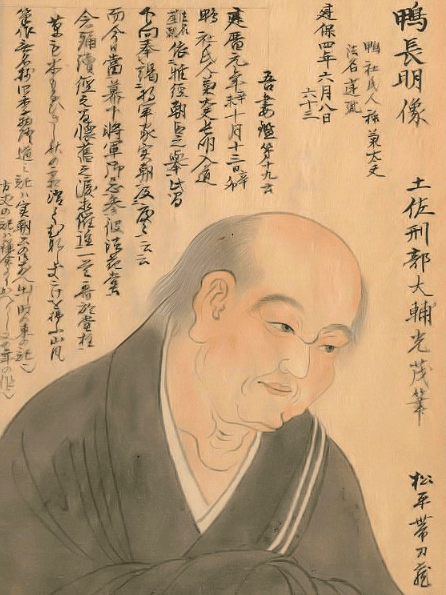

The Life of Kamo no Chōmei

Youth

Career and Disillusionment

Chōmei moved within the literary and musical circles of the court. He played the biwa – a lute with a soft, melancholy tone, ideal for reciting tales and poetry. His skills were appreciated by the most important families and powerful patrons, and his name began to appear in waka poetry anthologies. In an age when the ability to compose five lines of the right rhythm and mood could decide a career, Chōmei distinguished himself by his sensitivity and lightness of style.

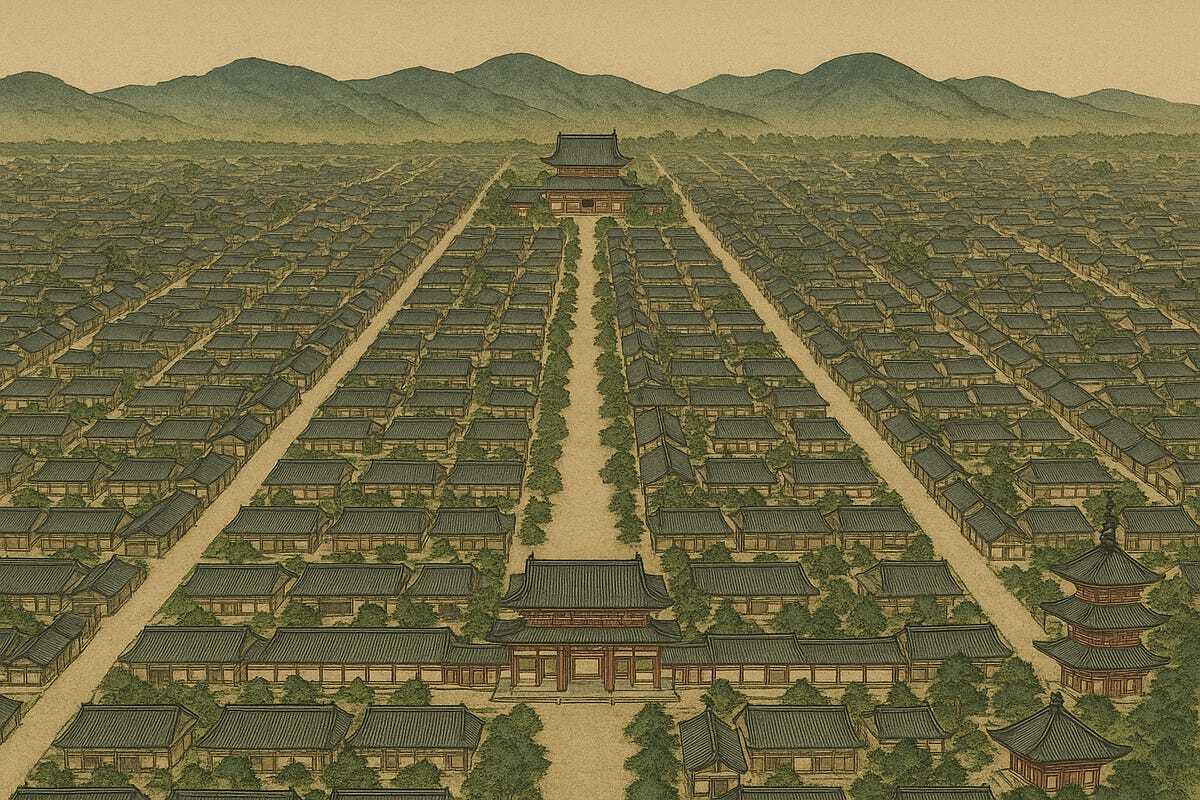

But court life in Heian-kyō had its dark side. The city, laid out according to ancient principles of feng shui and symbolic street arrangement, was as fragile as the paper houses its inhabitants lived in. In 1177, a great fire consumed much of the capital, the flames devouring temples, palaces, and noble residences. Before the city could rebuild, more blows came: in 1180, a major battle and fire during the conflict between the Taira and Minamoto clans; a few years later, floods and plague filled the air with the stench of death.

Though in youth Chōmei had won recognition, not all doors at court stood open to him. His father, as a priest of the Kamo Shrine, had secured him a good start, but after his father’s death the family’s influence waned. Chōmei had hoped for the post of chief priest at one of the prestigious Shintō shrines, but the lucrative position went to someone else – likely through the deft political manoeuvring of rivals. It was a bitter humiliation.

Personal losses – the deaths of loved ones, the breaking of old friendships, and perhaps unfulfilled affections (history, unfortunately, preserves no such intimate detail) – deepened his distance from the bustle of the capital. Though he still took part in poetry contests and continued to write, he was increasingly accompanied by the thought that beauty and fame were fleeting, and court life – empty (as is visible in the change of tone in his work). This was the stage of his life that prepared the ground for a radical step: leaving the city and renouncing his former life.

The Hermit’s Life

Chōmei matured toward his decision over many years. At the imperial court, he saw not only the beauty of calligraphed letters, refined poetic ceremonies, and the play of fans in the hands of court ladies, but also gestures laced with rivalry – gestures that had more in common with a blade hidden in a sleeve or poison in a meal than with a lyre. Though he gained fame as a poet and sat among the authors of imperial anthologies, he never attained the coveted position of chief guardian of the Kamo Shrine. His own words in Hōjōki betray this mixture of resignation and clear-eyed perception:

“A man is born and dies, comes and goes;

those I saw yesterday, today are no more.”

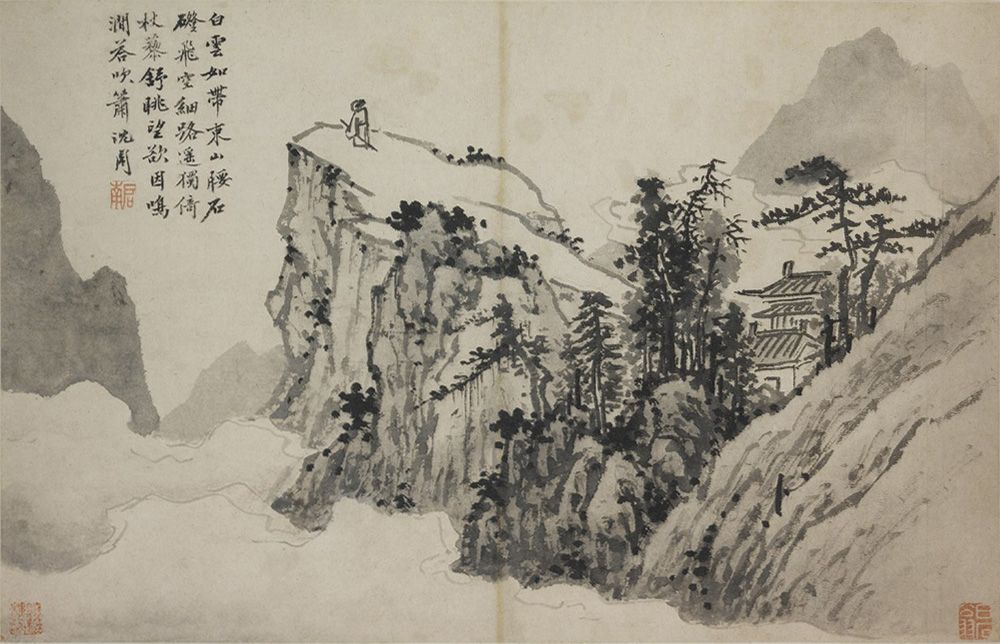

In this solitude, his philosophy ripened. In the spirit of the Buddhist teaching of mujo (impermanence) and the aesthetics of wabi-sabi, he observed how “the world is a river in which we never step twice, though the water always seems the same.” Yet his reflections were not detached from the world. He understood that impermanence was not a curse – it was the very core of beauty. In a yellowing leaf, in the weathering of the hut’s wall, in the shadow of a cloud moving across a slope, he saw not a flaw but a fullness that reveals itself precisely in the fact that it will vanish in the next moment.

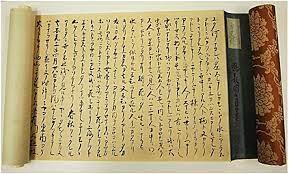

"Hōjōki"

方丈記

– Kamo no Chōmei (鴨長明), 1212, Hino Mountains

Hōjōki blends the author’s personal memories with the literary form of the essay and the philosophical treatise. It is a work of zuihitsu – written with a “brush following the thought” – but permeated with the Buddhist concept of mujo (無常) – impermanence. Chōmei, however, does not create an abstract meditation. Every passage grows out of his lived experience, and many of his images are brutally realistic.

The Prologue and the River Metaphor – the Impermanence of the World

“The river flows on without ceasing, yet the water in it is never the same. The bubbles of foam on its surface, vanishing and appearing again, resemble human beings and their fates – they appear and disappear, never lasting long.”

This is a metaphor of impermanence – of a world that seems to endure, yet whose elements are constantly changing. People’s houses may stand in the same place, but the residents leave, die, and new ones are born. The message is clear: nothing has a permanent form, and we humans are like those bubbles – transient and powerless.

This introduction sets the tone for the entire work. Chōmei shows that to understand the meaning of life, one must accept that everything is impermanent. Yet this is not a philosophy born in the quiet of a library – for Chōmei it grows out of real, painful experience.

Descriptions of Catastrophes – Fire, Earthquake, Storm, Famine

Fire (1177)

In Hōjōki, Chōmei recalls the great fire of the capital in the third year of the Angen era (1177), which destroyed a large part of the city – about one-third of Heian-kyō’s area. He wrote of how the houses of aristocrats and government buildings turned to ash, and of the desperate condition of the residents, forced to rebuild amid both spiritual and material emptiness.

Storm (1180)

Chōmei also describes the destructive hurricane that swept through the capital in the fourth year of the Jishō era (around 1180). Houses were destroyed across a wide area, including the districts of Nakanomikado, Kyōgoku, and Rokujō.

Famine (around 1181)

Famine (around 1181)

In the following years (the Yōwa era, around 1181) came drought, floods, and crop failure, which brought famine and epidemic. Chōmei recalls the slow death of the townspeople, the deserted fields, and the crumbling houses.

Earthquake (around 1185)

Hōjōki also contains an account of a powerful earthquake that occurred in 1185, destroying buildings, collapsing mountain slopes, and altering the landscape of the capital.

These descriptions are not merely a chronicle of events – for the author, they are tangible proof of impermanence. What in the prologue was the metaphor of the river is here demonstrated through fact. This is the design and structure of the work.

Reflection on Human Ambition

“Those who climb to the heights of power cannot sleep in peace – they fear the loss of their position. Those who do not have it burn themselves in the fever of desire.”

His diagnosis is unequivocal: ambition grants peace neither to those who long for it nor to those who have attained it. In the light of mujo, all this is futile effort, for positions, wealth, and fame are as impermanent as leaves carried on an autumn wind.

Withdrawal

Chōmei did not decide to withdraw immediately. First, he lost his position – he was passed over for the appointment of chief priest at the Kamo Shrine. In his account there is no bitterness, but there is a clear sense that the system in which he had lived was fragile and unjust.

“When there was no place for me in the city, I sought it among the mountains and rivers.”

Yet his motives went deeper than wounded pride. Chōmei saw in nature the reflection of a Buddhist truth – impermanence and peace. His decision to withdraw was not an escape, but a return to harmony.

Description of Life in the Hermitage

“In spring, I look at the flowers; in summer, at the moon. In autumn, I delight in the sound of wind in the pines; in winter – at the sight of snow. I need nothing more.”

Daily life was simple: gathering firewood, writing poetry, meditating, observing the changing seasons. In this simplicity, Chōmei found freedom from rivalry, from the expectations of others, and from fear of tomorrow.

Reflections on the Meaning and Transience of Life

The final paragraphs of Hōjōki are at once a confession of faith and a testament to reconciliation with the world. Chōmei repeats that everything is impermanent — but impermanence is no curse. It is a law of nature that allows one to accept life as it is.

"A man is born and dies like dew upon the grass. To understand this is to cease being afraid."

Buddhist wisdom here mingles with personal experience. Chōmei does not call for asceticism for all. His message is rather an invitation: if you wish to understand yourself, try looking at the world from a distance, even for a moment — like a monk in a hut on a mountainside.

How Do We Understand Hōjōki in the 21st Century?

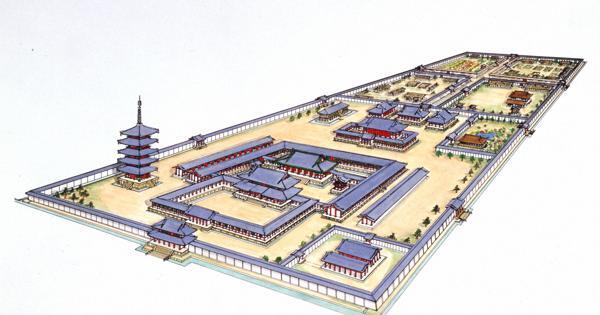

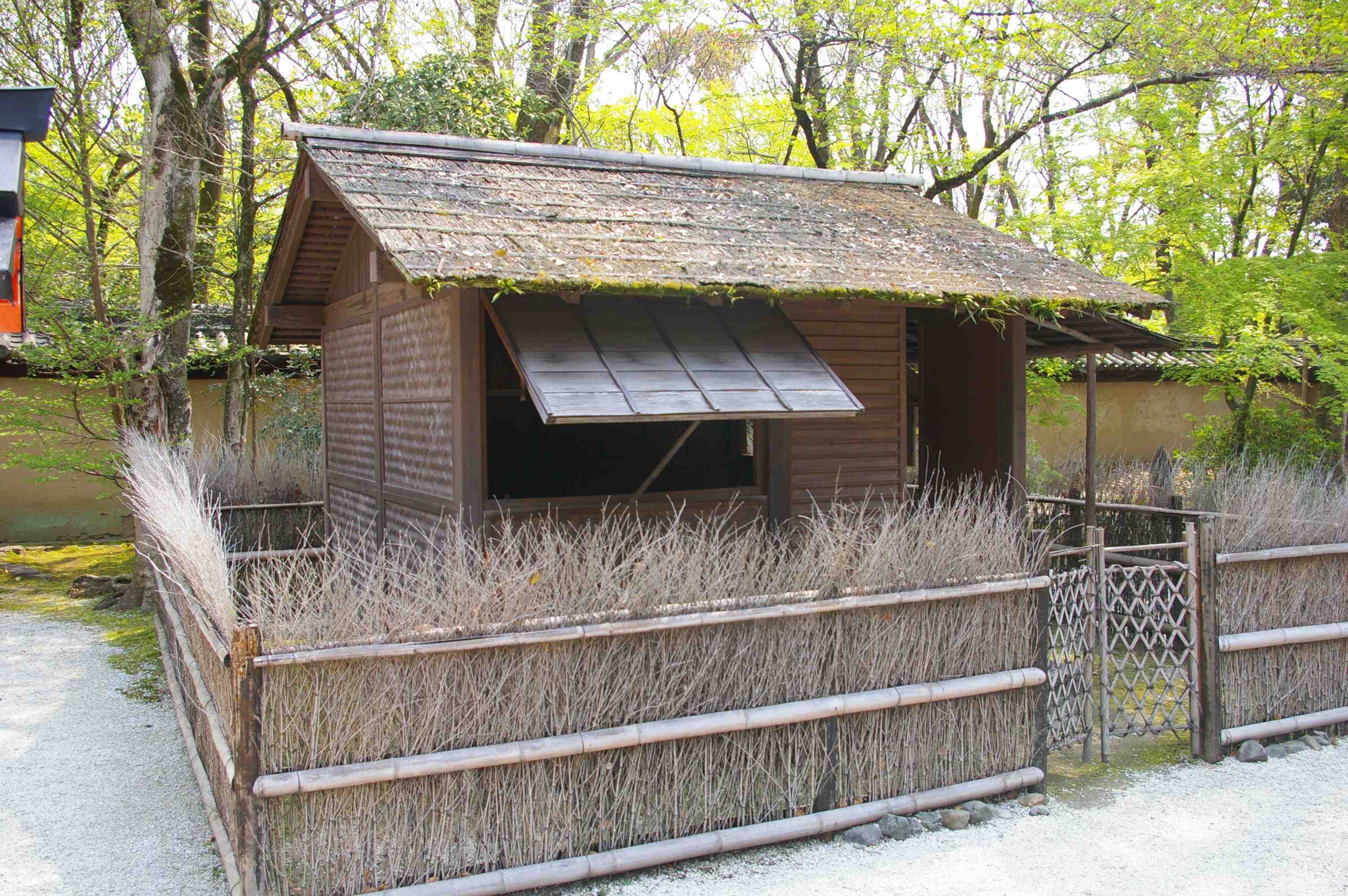

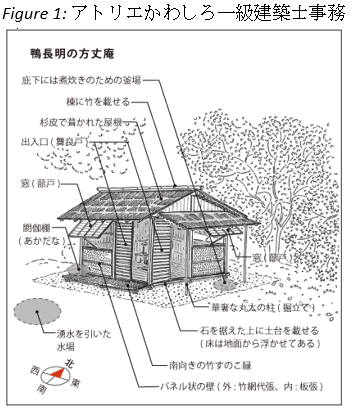

It is easy to call Hōjōki a treatise on transience. But that would be too flat. Chōmei not only speaks of impermanence — he constructs it in language, in architecture, and in lifestyle. His “ten by ten feet” is not a decoration but a philosophy put into practice.

Aesthetics

Two orders lie in the background of Hōjōki: Buddhist and Shintō. From Buddhism comes mujō and the conclusion that we suffer mainly because we cling to forms which, by definition, dissolve. From Shintō comes an elemental reverence for the landscape — the mountain, the river, the wind are not a “backdrop” to human affairs; they are co-protagonists. The collision of these orders yields in Chōmei a particular sensitivity: what perishes is at once beautiful and instructive. Aesthetically, it comes closest to the later named categories of wabi-sabi and mono no aware: the beauty of simplicity traced with a crack, the gentle sadness of things that pass. Importantly, this is not sentimentality. In Chōmei, simplicity is not “stylising oneself as humble,” but a reduction to needs with ethical consequences: fewer dependencies, less fear, more freedom.

Catastrophes

Fires, winds, famine, earthquakes — Chōmei does not describe them in order to build a lofty chronicle of disasters. Each event is an experience of the limits of control. In his logic, catastrophe does not contradict the order of the world; it strips bare the illusion that order belonged to man. That is why the solution is neither an escape into cynicism (“nothing has meaning”), nor an obsession with safeguards (“control everything”). The solution is a shift in the point of reliance: from things to practice, from possession to a way of being. Hence the decision for a hut that can be dismantled and moved; hence the hinges in the joints of the beams, the scale “for two carts” — minimalism not as a trend but as a technique of non-attachment.

Freedom

Chōmei does not promote “fleeing from people.” He chooses voluntary seclusion, which broadens the capacity to see. In Hōjōki there is the neighbour boy, there are walks to temples, there is the exchange of gifts with the valley. This is not misanthropy but selectiveness — a conscious limiting of the number of stimuli and roles. The key difference: seclusion has a vector from within (I choose the frames, the rhythm, the scale), isolation falls from without (I have been deprived of relationships). This difference translates into mental condition: in seclusion, agency grows; in isolation — helplessness. Chōmei shows that solitude can be a cognitive practice, not a wall, if it sustains a bond with nature and a few people.

Asceticism

Straight from Contemporary Japan

Interesting school ideas for implementing Chōmei’s philosophy in everyday urban life

Your Own “Four and a Half Tatami”

It is not necessarily a room; it is a scale. Ask yourself questions in the spirit of hōjō: What is the minimal space in which I can work and rest without distractions? What set of tools truly sustains my day? What can I make portable (routines, notes, exercises) so that “home” is more a way of being than an address? Sometimes it will be a desk disconnected from the net for two hours; sometimes a 30-minute walk along the same path without a phone; sometimes a weekend “hut in the city”: a flat functioning for two days in low-power mode.

Ritual of Opening and Closing the Day

Ten to fifteen minutes of looking at something constant (a tree, the sky, water), without a camera or notebook. This is your “hut window.”

Principle of Portability

Create a “minimal set” in each area (work, movement, reading, relationships) so that it could fit “on two carts”: in a backpack, in a single drawer, in a single file.

Week of Subtraction

Week of Subtraction

Once a month, remove one stimulus (notifications, excess meetings, impulsive purchases) and note the effect — not in terms of “productivity,” but mood and clarity of thought.

Practice of “Three Silences”

Five minutes in the morning, at noon, and in the evening — without eyes on a screen, with the breath counted to ten. This is the equivalent of a short nembutsu without metaphysics: a return to a single point.

Economy of Loss

Once a week, write down what was lost (time, plan, moods) and name it plainly. In Chōmei, recognising loss is an act of ordering the world — otherwise it accumulates in the background as nameless fear.

Map of Returns

Map of Returns

Choose two or three places in your surroundings that give a sense of constancy — they may be a bench in the park, a small bookshop, a café where only the hum of the espresso machine is heard. Return there at regular intervals, not for novelty but for repetition. These are your contemporary “landmarks” in a fluid world.

Meal of One Taste

Once a week, for one day, eat meals pared down to the limit — rice with salt, pasta with olive oil, a slice of bread and water. The point is contrast: when the world offers an excess of options, choose monotony deliberately. It is a reminder that satiety comes more from presence at the table than from the list of ingredients.

A Small Shadow on a Day of Full Sun

Choose a day on which you document nothing — no photos, posts, notes. Allow events to remain only in memory, even if tomorrow part of them fades. At the same time, pay attention to as many details as possible and try to remember everything. This trains acceptance of impermanence — something Chōmei knew all too well.

Pause at the Threshold

Pause at the Threshold

Before you enter a home, office, or shop, stop for a few breaths. Realise you are crossing the boundary of a space — just as crossing the threshold of Chōmei’s hut was entering a different mode of being. In an age when boundaries blur, the act of restoring them works like a reset.

Hōjōki does not propose escapism, but calibration: reduce the scale at which you must win for the day to be good; increase the scale at which you can find meaning even in change. Then the river — which we cannot stop anyway — ceases to be a threatening element and becomes something that carries you. And this is perhaps the most modern dimension of this thirteenth-century text: it does not promise that the world will calm down. It teaches how to calm the place from which you look upon the world.

Today

His “four and a half tatami” is not the relic of some ancient ascetic, but a way to survive any era — even one in which we seemingly can do anything, yet still so easily lose ourselves. Chōmei’s small house, whether made of wood and reed, or of a few chosen routines and thoughts, becomes the point around which one can draw a protective circle.

Perhaps here lies the universality of his lesson: not in advice on how to avoid catastrophe, but how to stand within it — with a heart that knows it is only a guest, and with a hand that, nonetheless, hangs a lantern in the window.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

How to Stop Fighting Yourself at Every Turn? Wabi Sabi Is Not Interior Design but a Way of Life

The Most Important Lesson from Musashi: "In all things have no preferences" (Dokkōdō)

Mastering One’s Desires: The Solitary Path of Musashi and Aurelius

Your Time is Your Space, Not a Frantic Race – 5 Japanese Lessons on Managing Your Own Time

Poetry with Sake – Master Senryū and His Joyfully Malicious Insight

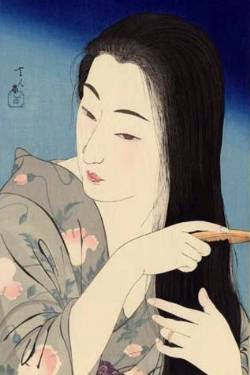

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Famine (around 1181)

Famine (around 1181)

Week of Subtraction

Week of Subtraction Map of Returns

Map of Returns Pause at the Threshold

Pause at the Threshold