Goze: Blind Female Artists of Feudal Japan – Dignity in a Journey through Snow and Rejection

Wandering in Darkness and Frost

Goze were not just artists. In folk imagination, they were more – beings on the threshold. Their songs had the power to influence harvests, health, fate. They were blind, but they saw through sound; they were women, but forbidden to love or be loved; they were free, yet bound by an oath of strict rules. They lived on the margins of roads, in the cold of winter and the silence of rural nights. Their lives consisted of song, wandering, and the memorization of an incredible number of verses. And yet, within this loneliness and austerity lay a deep spirituality: humility before fate, discipline, community, and art – as a means of saving oneself in a world that left no room for the weak. Goze did not sing out of passion. They sang because only in song could they be something more than a body without sight – they could become a story itself.

A Day in the Life of a Goze

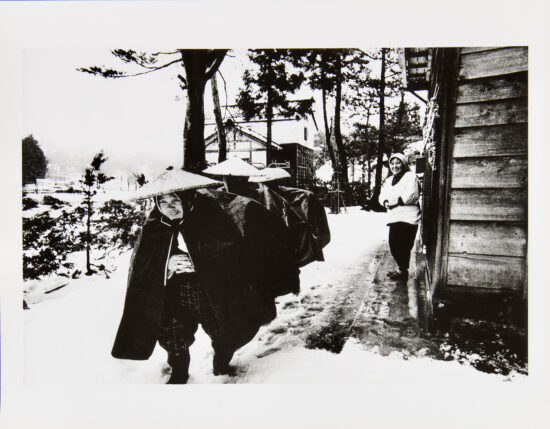

They travel from village to village, as they do most of the year – except for the few deep winter months, when the snow is too merciless even for them. But today, in the early morning, they set off – to a performance that will take place in a farmer’s cottage, where they’ll spend the night. Their backs ache from the heavy furoshiki that contains their whole world: an extra kimono, a rice bowl, an instrument, a second shamisen wrapped in cloth. Each carries about thirty kin (approximately 18 kg). They are self-sufficient. That is part of their pride.

Tonight, they will sing danmono (段物 – multi-segmented song) – a long, multipart tale of love and betrayal. Then someone will request a kudoki (口説き – lamentation song) – a song of lovers’ suicide. And then the children will ask for a cheerful min’yō (民謡 – folk song). Goze must know everything. Remember everything. They do not have scores. Their sheet music is muscle memory – fingers, breath. Sounds are their map – and compass.

After the performance – a modest supper. A bowl of hot rice with salted plums. Sometimes a bit of fish. Sometimes not. Then silence. Aki lays down to sleep on a straw mat by the wall. Hanayo softly whispers a prayer to Myōonten – their patroness, goddess of music and voice.

They believe she was the daughter of an emperor, blind from birth, sent to earth to guide other blind women. They believe it is she who gives them the voice that does not tremble, even when the heart is afraid.

Closing her eyes – which see nothing anyway – Aki thinks of tomorrow. Of the next village. The next performance. The next bowl of rice. Of her teacher, who may one day give her the han-eri – the sign that Aki has become goze not only in body, but in spirit. It is purple in color, though Aki does not know what that truly means. She must sleep – tomorrow is another day of walking through frost and mountains to the next village.

What Does “Goze” Mean?

The character 瞽 is rare, archaic, and historically marked. In the past, it also appeared in compounds referring to blind male players of the biwa (e.g., gishi – 瞽師), but it has survived the longest in the word goze. It carries the weight of fate, the stigma of physical deficiency, and at the same time a shadow of mystery – for in Japanese culture, a blind person was not only considered disabled but often endowed with special sensitivity or access to “another world.”

It is also important to distinguish between written and spoken language. In documents – names of organizations, chronicle records – the spelling 瞽女 was used. But in living speech, dozens of terms circulated, often emotionally, locally, and colloquially marked – many of which are now fading into oblivion. Language, as always, is not only a tool for description but a mirror of society’s gaze – full of ambiguity, emotion, fear, and admiration. The name goze is thus not merely a professional designation – it is a word that carries both the burden of fate and the light of dignity.

What Kind of Society Did Goze Live In?

Families, especially in the countryside, feared that a blind daughter would bring disgrace upon the household. Superstitious fears would arise – that it was a “punishment from the heavens” – but also practical concerns: that no one would marry her, that she wouldn’t be able to work in the fields, that she would become a burden. For poorer households, this meant the necessity of giving the child away – out of pity, desperation, but also calculation.

Against this backdrop, goze appeared as a third path – not as an act of mercy, but as a strict structure of mutual aid, based on art, discipline, and dignity. Entering a goze organization was not so much a choice as a rescue – a way to avoid the worst fate. It was a model of emancipation through rigor, not leniency.

For a blind woman, this was often the one and only way to survive with dignity – not as a beggar, not as a “curiosity,” not as a medium or slave, but as an artist and a pilgrim. Goze did not ask for pity. Goze gave song.

The History of Goze

Everything began to change with the arrival of an instrument that forever altered Japan’s soundscape – the shamisen. This three-stringed instrument, brought from China via Okinawa and Kyoto, became widespread during the Edo period. The shamisen became the heart of goze music – a tool of storytelling, lyricism, and drama. From that moment on, goze from rural areas began to organize into formal groups – with hierarchy, rules, rituals, and repertoire.

– Takada (modern-day Jōetsu, Niigata Prefecture),

– Nagaoka,

– Iida (Nagano Prefecture),

but also in other regions: Yamagata, Saitama, Gifu, Akita.

These communities, often called goze-kō (瞽女講), functioned like artistic monastic orders – with their own rules, elders, training structures, behavioral codes, celibacy laws, and strict punishments for violations. They were often morally ambiguous – some goze groups came into contact with pleasure quarters (yūkaku), offering entertainment in establishments of various character. But the most respected among them protected their reputation with iron discipline.

Over time, however, everything began to change. The Meiji era (1868–1912) brought modernization, the collapse of old social structures, new institutions, and a different conception of disability. Goze – as a way of life based on a medieval model of survival – began to vanish from the social landscape. After the war, only a few elderly women remained, continuing the tradition – often as living relics of another world.

The Last of Them Was Haru Kobayashi (1900–2005). She is recognized as the last true goze of Japan. Born blind, she began her training at the age of nine within the Takada-goze organization, and for over eighty years she performed, learning more than one hundred songs. In 1971, the Japanese government recognized her singing as an intangible cultural heritage, and in 2005, upon her death, the living history of goze came to an end.

Not necessarily.

The contemporary researcher and singer Rieko Hirosawa has for years studied, reconstructed, and performed goze songs, restoring not only the music but also a way of life, of thinking, of seeing the world without using one’s eyes. Thanks to figures like her, goze are returning – as a cultural phenomenon, a subject of reflection, a symbol of dignity that does not need sight to see deeply.

Everyday Life Within Strict Rules

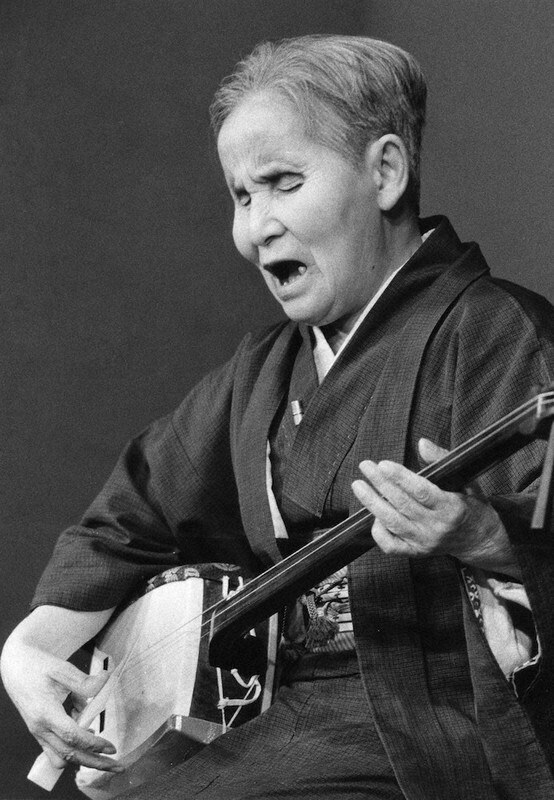

The hierarchy was clear: the shishō (師匠 – master) led the community, passed on the repertoire, and oversaw discipline. Senior goze were obligated to teach the younger ones, guide them during travels, and evaluate their progress. Apprentices – often very young girls – learned not only how to sing and play the shamisen, but also how to live: how to move without sight, memorize the layout of a room, use chopsticks, dress, bow, remain silent. Silence was a virtue.

The rules were written – in the form of codes – and were recalled annually during the Myōon-kō (妙音講 – literally “gathering of subtle sound”) ritual. This was an annual assembly of goze from a given region, during which they sang together, recited the foundational legend (about a blind woman who turned suffering into song), read aloud the rules, and swore to uphold them. It was a time of community, purification, renewal – but also of scrutiny and judgment.

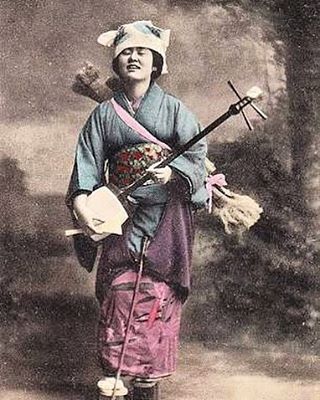

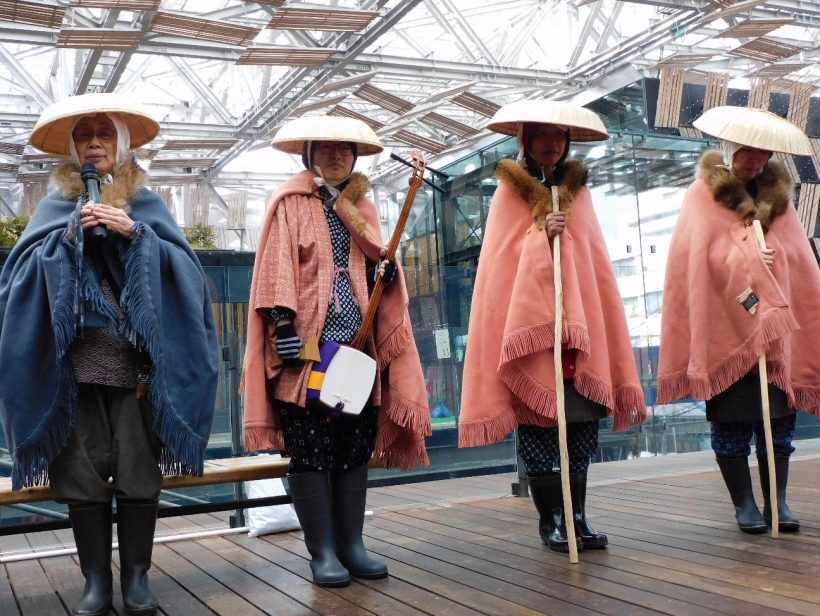

Everyday life followed the rhythm of study and travel. Goze spent as many as 300 days a year on the road – on foot, with staff and instrument, along mountain paths, snow-covered roads, across bridges, through rural temples and highways. They traveled in groups, one behind the other, with a hand on the shoulder of the older sister. They carried a shamisen in its case, a few modest garments, and the memories of routes they knew by heart.

They performed in peasant homes, sometimes in village inns, other times in midwives’ rooms, temples, at festivals, by bonfires. Lodging was provided by so-called goze-yado (瞽女宿) – rural homes with a tradition of hosting goze. Sometimes these were friendly households, sometimes families of former apprentices, sometimes rooms set aside especially for them. In exchange for music and blessings, hosts offered simple food, a place by the fire, a bit of rice for the journey. It was said that rice given to goze brought fertility, strength, and good fortune.

Often, they were accompanied by tebiki (手引き) – sighted women who acted as guides, assistants, and at times companions. They were not goze, did not know the songs, but they knew the roads, offered protection from danger, helped carry instruments, and spoke with hosts.

This life – austere, nomadic, full of rules and solitude – was also a form of autonomy and spiritual depth unlike any other female community of the era. Goze lacked sight – but they had song, sisterly bonds, and freedom.

Repertoire and Musical Style

Training, for obvious reasons, was entirely oral – without writing or musical scores. The master would sing line by line, and the apprentice would repeat until perfection. Goze could memorize hundreds of songs, sometimes lasting for hours, with all the nuances of intonation, pauses, breath, and accent. This was not just memory – it was spiritual transmission.

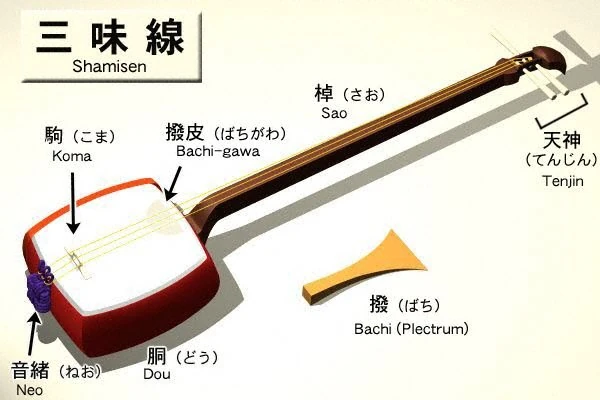

Their primary instrument was the shamisen (三味線) – a three-stringed, plucked instrument with a rectangular body covered in skin (often cat or dog), played with a large plectrum (sometimes made of tortoiseshell). The sound of the shamisen was dry, brittle, with a faint metallic echo – like the echo of footsteps on winter earth. Combined with a low, subdued voice, it created an ascetic yet hypnotic aura.

Appearance and Clothing

Their baggage – though seemingly modest – weighed several kilograms and symbolized self-sufficiency. Goze did not ask for help – they carried everything they owned on their own backs. Every knot in the furoshiki, every fold in the kimono had its place – once learned, they repeated it for years, in darkness, by memory and touch.

The aesthetics of their performance did not end with clothing. Song, movement, silence, the pauses between verses, the manner of sitting by the fire, the way hands were placed – all of it was part of a ritual, as if each song were a tea ceremony – only of sound. There was no room for improvisation – there was form, and within it lay an ethic of life.

Goze and Society – Magic, Respect, Exclusion

In many regions of Japan, there was a belief that goze possessed a power – not magical in the ritualistic sense, but spiritual, liminal. Because they had been stripped of one of the primary senses, they were thought to be closer to spirits, kami, ancestors. Their songs could encourage silkworms to spin cocoons, ensure bountiful harvests, bring health to children. That is why rice given to goze was not merely payment, but a magical gift – a form of exchange with someone who transcended everyday boundaries. There even existed a phrase: goze no hyakunin-mai (瞽女の百人米) – “rice of a hundred people for one goze” – as a metaphor for generosity, but also hope that through the goze’s song, the entire community would be blessed.

And yet – that respect did not preclude distance. Goze lived on the margins – physical, social, and emotional. They belonged neither to the world of mothers, nor to the world of priestesses, nor to the world of courtesans. They were a separate class, with their own code, aesthetic, and fate. Not infrequently they were insulted: mekurakko (blind girl), tochi (stray vagabond). They were respected and simultaneously stigmatized – as so often happens with those who do not fit into obvious social roles.

Philosophy, Spirituality, the Meaning of Life for Goze

The singing of goze – so distinctive: restrained, pure, without expressive vibrato – reflected a philosophy in which emotions are deeply felt, but not displayed. Dignity is not an escape from suffering, but its transformation into something more subtle: story, sound, rhythm. Their lives were not founded on the pursuit of happiness in the Western sense, but on acceptance of pain and the transformation of lack into presence.

Haru Kobayashi, the last of the great goze, once said:

“Kami see the heart. Even if I am reborn after death as a worm, I want to have sight.”

This sentence – seemingly paradoxical – speaks of a longing for recognition, of the right to inner light even in a world of darkness. Kobayashi had been blind since birth, yet her musical memory, psychological strength, and spiritual discipline made her a bridge between eras.

Goze taught that pain could be a path, that solitude could be a source of sound, and that silence could carry more meaning than words. In a world founded on sight, they – without eyes – taught how to see more deeply. In a world full of noise and haste, their slow wandering and evening songs beneath a thatched roof carried a different kind of time – a time of focus, memory, and presence.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Born in hell, buried in Jōkanji – what have we done to the thousands of Yoshiwara women?

Women of the Yakuza – Silently Bearing the Scars on Their Bodies and Hearts

The Invisible Woman – Life as a Samurai’s Wife

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!