Genji and Yugao – The Secrets of the Moonflower in a Millennium-Old Tale of Desire and Loss

Among the Moonflowers

It is a tale of love that blossomed in the shadow of ruins and a spirit that destroyed that love. Hikaru Genji, the prince—a favorite of life itself—turned his gaze toward a mysterious woman hidden behind the veil of an abandoned house. Their love was like a moonflower in the night—beautiful, ephemeral, yet born in the knowledge of its imminent downfall and end. In moments of tenderness, as two souls intertwined under the cover of darkness, desire and jealousy clashed, summoning a dark presence from the shadows—a presence that silently devoured their love. Yūgao died suddenly, and her death drove poor Genji to the brink of despair and madness, leaving him with questions that only the pale and eternally indifferent moon could answer.

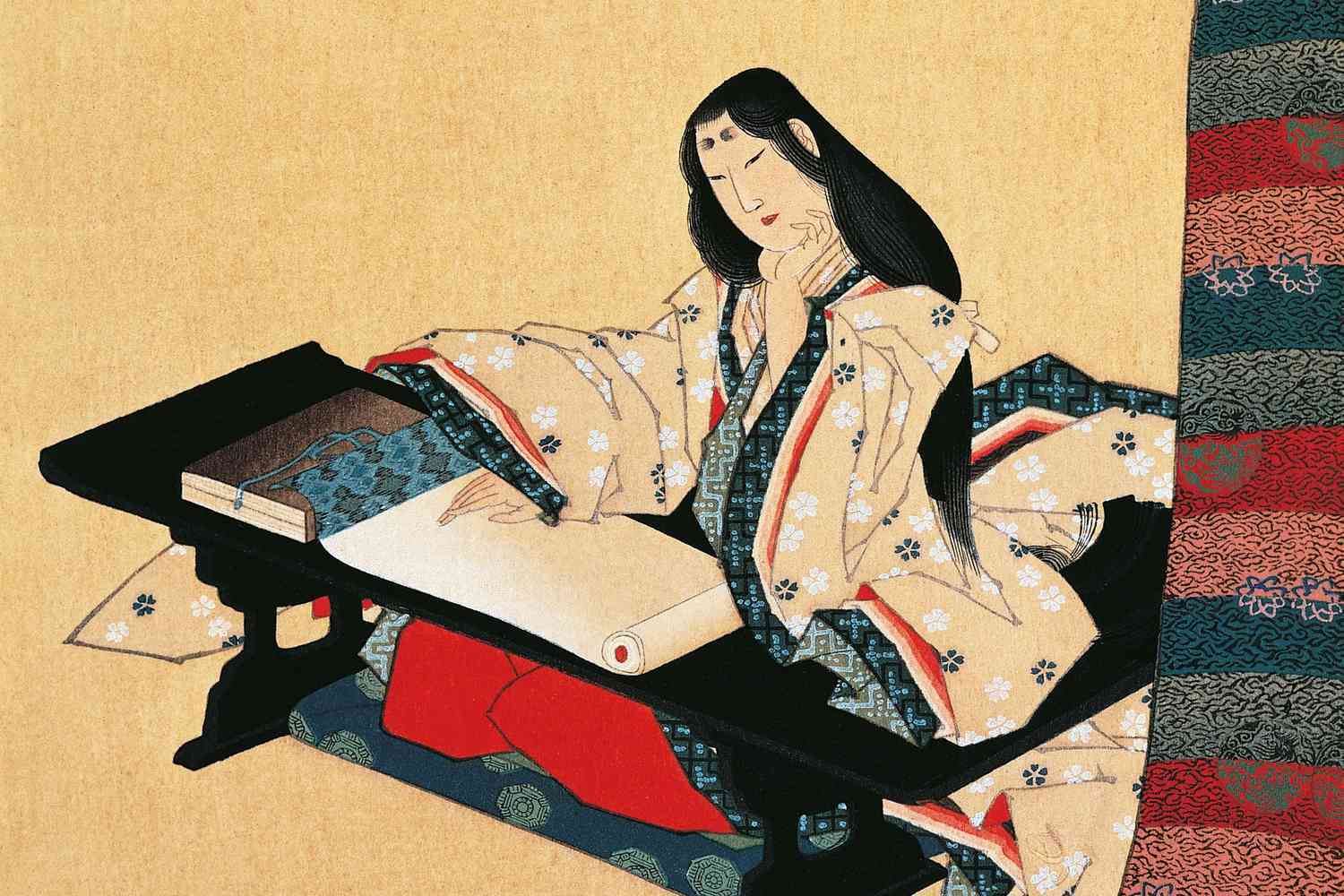

Who Was Murasaki Shikibu and What Is The Tale of Genji?

The popularity of The Tale of Genji as an artistic inspiration is immense. The novel has inspired hundreds of works of art, including around 1,000 ukiyo-e prints that capture both the most dramatic and the most subtle moments from the book. Moreover, the novel has been adapted into various performing arts, such as nō theater, kabuki, and even contemporary mediums, including anime.

"Genji and Yugao"

源氏と夕顔

(Genji to Yūgao)

- Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (月岡芳年)

“One Hundred Aspects of the Moon” (月百姿)

The figure of Yūgao is depicted in a moment when her ethereal nature crosses the boundary between life and death. Her silhouette is otherworldly and intangible. Delicate, almost translucent lines outlining her body emphasize her ephemeral nature, while the pale tone of her skin contrasts with the dramatically darker, more vibrant background. Yoshitoshi employed a refined interplay of light shades of blue and white, making her face, illuminated by the pale moonlight, exude melancholy and mystery.

Yūgao’s hair, long and unkempt, flows over her shoulders like black waves of a stormy sea. This hairstyle, characteristic of Heian-period women, appears slightly disheveled in Yoshitoshi’s interpretation, further highlighting her spiritual, incorporeal presence. Yūgao’s eyes, painted in cool, bluish hues, seem vacant, expressing something between pain, resignation, and mystery. Her bluish lips, exuding the chill of death, add to her beauty while enveloping her in an aura of darkness.

At the heart of the painting lies Yūgao’s figure, but it is the surrounding details that complete the composition. The moonflowers (Japanese: yūgao), winding around her figure, are depicted with extraordinary precision. Their long stems and delicate petals seem almost alive on the paper. These flowers symbolize both beauty and transience, their whiteness nearly merging with Yūgao’s pale complexion. Meanwhile, the curling stems appear to ensnare her, as if holding her in their grip, emphasizing her state of entrapment between life and death.

Yoshitoshi employed typical ukiyo-e techniques, such as flat color planes and precise contours, but infused his style with subtle gradients, adding depth and three-dimensionality to the painting. The use of cool, muted tones—from soft blues to deep navy—underscores the atmosphere of melancholy and dread. At the same time, the intricate depiction of flowers and textiles reflects inspiration from traditional decorative patterns, which held significant cultural value in Japan.

The painting “Genji and Yugao” is not merely a depiction of a beautiful woman or a decorative scene from a classic text. Every detail tells a fragment of a larger story. To fully understand this painting, we must delve into the story of the fateful meeting between Genji and Yūgao, which brought love, death, and the shadow of eternal sorrow. Let us return to Murasaki Shikibu and her Genji Monogatari, specifically Chapter IV, titled “Yūgao,” which immerses us in a world of subtle emotions, mysteries, and tragic love.

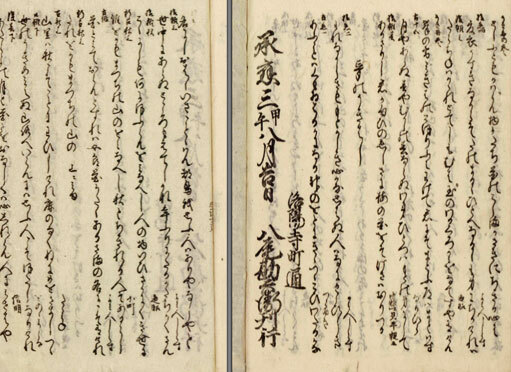

"Genji Monogatari, Chapter IV: Yūgao"

源氏物語 第四帖: 夕顔

(Genji Monogatari, Dai Yon Jō: Yūgao)

- Murasaki Shikibu (紫式部)

The Tale of Genji (源氏物語)

The First Encounter Between Genji and Yūgao

The Encounter

Fascinated, Genji decided to act cautiously. In accordance with tradition, he composed a waka poem for the lady of the house, which he sent through her maid. The following evening, he managed to engage the maid in conversation when she brought him a response to his poetic offering. Although her words were brief, they revealed that her mistress valued poetry and beauty, which only deepened his fascination. Genji asked the maid to deliver a message, subtly expressing his interest in her mistress—phrased, of course, in a highly veiled manner befitting courtly etiquette.

A few days later, to his delight, Yūgao responded—first delicately, through her poems, and later, as trust grew between them, she met with him in person. Genji began to visit her secretly more and more often, and with each conversation, each glance, her smile lit up his soul. Yūgao, though shy, felt something stir within her in his presence—an emotion she had never known before, a mixture of fascination and fear. She hesitated to reveal her past, though her secrets cast a shadow over their blossoming relationship.

The Meeting in the Secluded House

In the remote house, the atmosphere was both intimate and fraught with tension. Moonlight streamed through the empty frames of the windows, illuminating their faces and revealing the emotions they struggled to contain. That night, their love fully blossomed—Genji’s tenderness brought Yūgao a moment of solace and happiness. But the night held its own secrets, and the silence concealed something more than the soothing rustle of the wind.

Revenge

From the darkness emerged a malevolent presence—a spirit whose anger and sorrow were almost tangible. It was the manifestation of the extreme emotions of Rokujo no Miyasudokoro (六条御息所), a former lover of Genji. Rokujo, a woman of great pride and sophistication, was not only marked by her aristocratic grace but also by an unbridled jealousy and bitterness toward Genji. Once, she had basked in the attention of the "Shining Prince," but Genji, captivated by new loves, had relegated her to the background. Humiliated and abandoned, Rokujo could not bear the thought of another woman taking her place beside Genji.

A cold draft swept through the room, and Yūgao, who had moments earlier nestled in Genji’s arms, began to shiver as though touched by icy fingers. The air grew thick, and from the darkness emerged a vague, sinister silhouette. The ikiryō, though incorporeal, radiated an intense energy that drained Yūgao, as if her life force were being sapped. Genji, confused and terrified, tried to revive her, but he was powerless against the supernatural force. At dawn, as the first rays of sunlight pierced the darkness, Yūgao passed away quietly, leaving Genji in despair and guilt that would haunt him for years to come.

Genji’s Despair

This love, though brief, changed Genji forever. In the shadow of grief from losing his beloved, he saw the pain of life and the beauty of fleeting moments entwined. Yūgao became, for him, a symbol of life destined to fade—like a flower that blooms for a fleeting moment, only to disappear, leaving behind an echo of ephemeral beauty. This theme would become a central axis of Japanese culture for a millennium, eventually receiving the name mono no aware during the Edo period.

Yūgao embodies the concept of mono no aware (even though the term did not exist at the time)—her life and death remind us that the most beautiful moments are, by nature, fleeting. This story shows that in pursuing the fulfillment of our desires, we often face forces we cannot understand or overcome—such as the ghosts of the past or fate, which inevitably leads to loss.

Looking at the whiteness of the yūgao flowers, Genji saw more than the memory of his beloved—he saw himself, striving to grasp the elusive essence of life. This love, though painful, taught him humility in the face of fate and helped him understand that every shadow—even the darkest—exists because of the light. Yūgao, though gone, left an eternal mark on his heart—a warning and, at the same time, a hymn to the fleeting beauty that makes life truly human.

What Can We Learn From Murasaki Shikibu’s Story of Genji and Yūgao?

We live in times where it is easy to lose ourselves in haste and clamor, but the story of Genji and Yūgao offers us a timeless lesson: everything precious will pass—whether or not we manage to appreciate it. The world will not wait for us.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

The Author of the World's First Novel: Meet the Strong and Stubborn Murasaki Shikibu (Heian, 973)

How to Stop Fighting Yourself at Every Turn? Wabi Sabi Is Not Interior Design but a Way of Life

The Most Important Lesson from Musashi: "In all things have no preferences" (Dokkōdō)

“Yasumasa Playing the Flute” by Yoshitoshi – Art and Violence on the Plains of Ichiharano

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!