He walked the path of peace and tea, of sword and blood

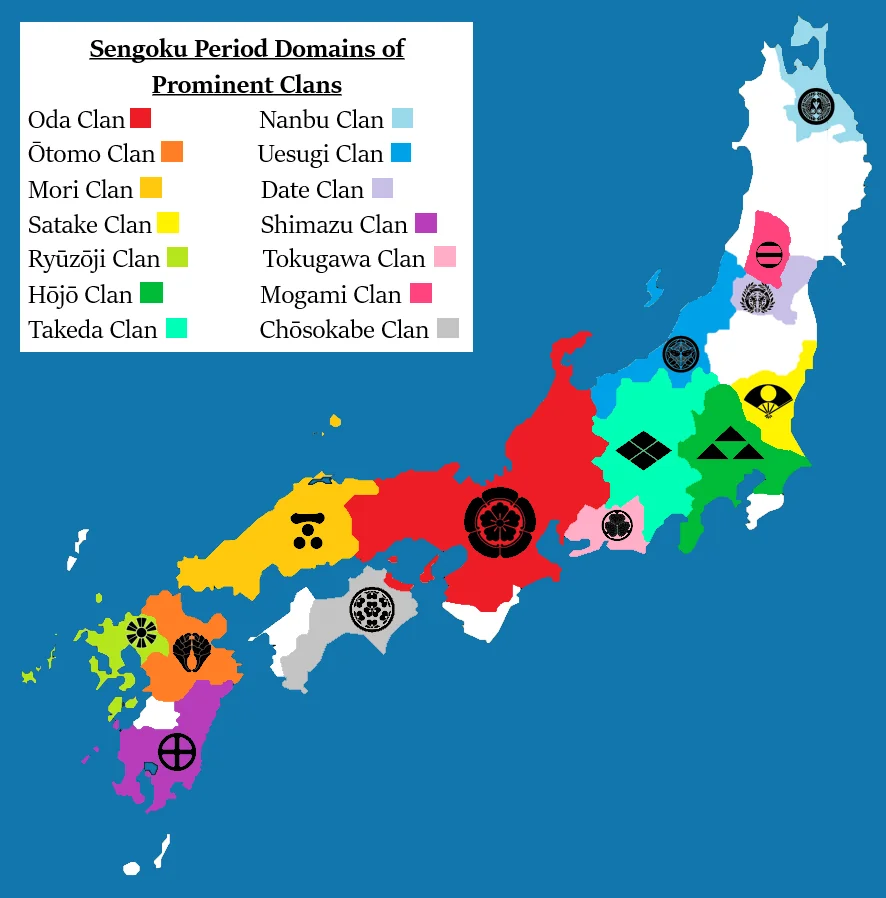

Japan during the Sengoku period (15th–16th century) was a land drenched in blood, torn apart by a multi-generational war between provincial rulers – the daimyō – where successive generations of samurai knew only the language of sword and fire, training physically to kill with perfection and spiritually – to be ready for death at any moment. In these times lived a man who defies easy categorization – a warrior with the soul of an artist, a ruthless strategist and a subtle master of tea, who wielded death and contemplated the aesthetics of the moment with equal skill. Furuta Oribe – from the perspective of our time and culture – a man of paradox.

Japan during the Sengoku period (15th–16th century) was a land drenched in blood, torn apart by a multi-generational war between provincial rulers – the daimyō – where successive generations of samurai knew only the language of sword and fire, training physically to kill with perfection and spiritually – to be ready for death at any moment. In these times lived a man who defies easy categorization – a warrior with the soul of an artist, a ruthless strategist and a subtle master of tea, who wielded death and contemplated the aesthetics of the moment with equal skill. Furuta Oribe – from the perspective of our time and culture – a man of paradox.

Oribe was a samurai who survived the most brutal campaigns of the Sengoku period and simultaneously a sensitive artist who designed original ceramics resembling a dream, kabuki theatre, or a grotesque vision straddling heaven and battlefield. A close associate of two unifiers of Japan – Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi – he was also a student of the great Sen no Rikyū, a witness to his tragic downfall, and the birth of a new order under Tokugawa rule. There is nothing predictable in his life – neither on the path of war, nor on the path of tea. He moved through palaces, battlefields, and tea pavilions with the same attentiveness, seeking not harmony, but truth – often ugly, strange, irregular.

Oribe was a samurai who survived the most brutal campaigns of the Sengoku period and simultaneously a sensitive artist who designed original ceramics resembling a dream, kabuki theatre, or a grotesque vision straddling heaven and battlefield. A close associate of two unifiers of Japan – Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi – he was also a student of the great Sen no Rikyū, a witness to his tragic downfall, and the birth of a new order under Tokugawa rule. There is nothing predictable in his life – neither on the path of war, nor on the path of tea. He moved through palaces, battlefields, and tea pavilions with the same attentiveness, seeking not harmony, but truth – often ugly, strange, irregular.

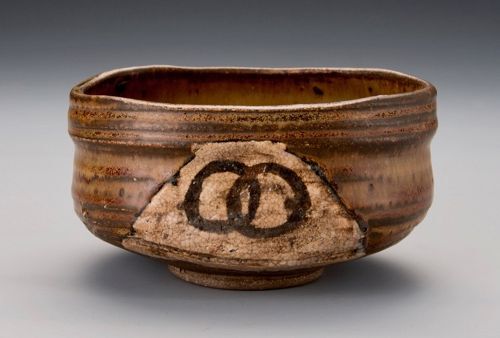

For how can one reconcile the two? How can a brutal killer live within the same man who wakes each morning and sleeps each night with the scent of blood and the groans of the wounded in his ears – and yet is also a master of the tea ceremony, who spends an hour contemplating the line of glaze running down the uneven edge of a tea bowl? Oribe broke rules not only on the battlefield – he shattered the dogmas of traditional Japanese aesthetics as well, creating his own provocative philosophy of Oribe no bi – the beauty of asymmetry, of the grotesque, of the unexpected. We owe to him the vivid green Oribe-yaki vessels, full of irregular forms and bold decorations, as well as daring innovations in the tea space itself – from room layouts to the behavior of guests.

But such creative freedom has its price. The era of Sengoku wars came to an end, and in the world of the Tokugawa shogunate, which pursued harmony, control, and rigid hierarchy – there was no place for artistic rebellion. Even though Oribe was the tea master to the second Tokugawa shōgun, even though he was one of the most outstanding artists of his era – Furuta Oribe was ultimately forced to commit seppuku. He died in silence, like many before him – but what he left behind still resonates in tea pavilions to this day. Let us now discover his life.

A child of the age of chaos – the birth of Furuta Shigenari

The scent of steel and mud, the taste of dust and blood – Japan of the Sengoku period

The scent of steel and mud, the taste of dust and blood – Japan of the Sengoku period

Mid-16th century Japan was a stage – bloody, torn, and unpredictable – upon which an endless tragedy unfolded, of people caught between loyalty and survival. Instead of one crown – hundreds of lords. Instead of one empire – an archipelago of kingdoms. The so-called Sengoku period, the “Warring States era,” was a time when the shogunate had effectively collapsed, and each daimyō – a local warlord – fought for control over his own and neighboring provinces. Borders were fluid, and life – short.

Villages burned, castles rose and vanished into ash, and samurai children grew up knowing nothing but physical training to kill, and mental training to accept death. Winter mornings were not broken by birdsong, but by the screams of the wounded and the steel sound of kirigane. The entire culture was steeped in war: the aesthetics of the sword ruled fashion, architecture, cuisine, and language. Honor was measured in blood, and the greatest virtue was not land or gold, but loyalty – as fickle as the wind in the valleys of Gifu.

And yet – paradoxically – it was precisely in this vortex of blood and chaos that the most delicate expressions of Japanese culture were born: chanoyu, zen gardens, calligraphy, and ceramics. For where death is near, art sharpens the senses to the fragility of the moment. It was in such Japan, at the intersection of sword and tea bowl, that Furuta Shigenari (古田 重然) was born – later known as Furuta Oribe.

The birth of Furuta Shigenari

The year was 1543 – a time when Portuguese merchants first brought firearms to Japanese shores, and Oda Nobunaga was only beginning to dream of marching toward power. In the province of Mino, located at the crossroads of key trade and war routes, a boy was born into a mid-ranking samurai family who would go down in history not only as a warrior alongside the Unifiers of Japan, but also as an aesthete. He was given the name Shigenari, and although the Furuta clan was not among the most powerful, it enjoyed the respect of local lords and had strong ties to Oda’s court.

The year was 1543 – a time when Portuguese merchants first brought firearms to Japanese shores, and Oda Nobunaga was only beginning to dream of marching toward power. In the province of Mino, located at the crossroads of key trade and war routes, a boy was born into a mid-ranking samurai family who would go down in history not only as a warrior alongside the Unifiers of Japan, but also as an aesthete. He was given the name Shigenari, and although the Furuta clan was not among the most powerful, it enjoyed the respect of local lords and had strong ties to Oda’s court.

The land of Mino itself was a singular cradle for a future innovator. Here lay the famous village of Seto, the heart of Japanese ceramics, where for centuries vessels for tea, incense, and sake had been fired. Smoke rising from the kilns mingled with the scent of mud, ash, and pine needles – and perhaps this was one of the first scents little Shigenari remembered. In the shadow of the black smoke, his sensitivity to the texture of earth, the color of clay, the sound of a fired bowl began to grow.

The land of Mino itself was a singular cradle for a future innovator. Here lay the famous village of Seto, the heart of Japanese ceramics, where for centuries vessels for tea, incense, and sake had been fired. Smoke rising from the kilns mingled with the scent of mud, ash, and pine needles – and perhaps this was one of the first scents little Shigenari remembered. In the shadow of the black smoke, his sensitivity to the texture of earth, the color of clay, the sound of a fired bowl began to grow.

As the son of a samurai, he was trained in the art of the sword from an early age. He practiced kata with a wooden bokken, studied the rules of the honor code, and recited verses from the Heike monogatari, where the aesthetics of death mingled with the drama of history. But at the same time – in family rooms warmly lit by a muted lamp – he watched his father lay out tea utensils with almost religious reverence. The sight of a tea bowl placed on a bamboo mat with more solemnity than a katana on its stand could not help but impress his young imagination.

His father, like many mid-ranking samurai, nurtured a love for tea – not only as a ritual, but as an expression of sensitivity, spiritual discipline, and a moment of silence amid the din. In the family tea pavilion, he hosted ceramic masters from Seto, wandering zen monks, and artists of ink and word.

Between morning kenjutsu training and evening ceremonies with his father, he grew up torn – but also enriched – between the world of brutal reality and the world of quiet beauty. He learned that in Japan, nothing is unambiguous: ugliness can be beautiful, deformation can be true, and a tea bowl can be a battlefield.

Youth and first political maneuvers

Before we enter the path of tea in the life of Furuta Shigenari, we must pause for a moment on the figure of the man who left a powerful mark on the young samurai’s fate (and on the whole country) – Oda Nobunaga (織田 信長). Nobunaga, the first of Japan’s three Unifiers, was like a storm sweeping through a land engulfed in war. Born in 1534, he gained fame not only as a ruthless strategist, but also as a visionary who sought to unify a fragmented Japan under a single rule. He was like a dragon with iron wings – brutal and merciless toward enemies, yet modern in thought: the first to make significant tactical use of firearms, he broke with aristocratic etiquette and surrounded himself with capable people regardless of their birth. In his shadow grew future great generals and artists – including the young Shigenari.

Before we enter the path of tea in the life of Furuta Shigenari, we must pause for a moment on the figure of the man who left a powerful mark on the young samurai’s fate (and on the whole country) – Oda Nobunaga (織田 信長). Nobunaga, the first of Japan’s three Unifiers, was like a storm sweeping through a land engulfed in war. Born in 1534, he gained fame not only as a ruthless strategist, but also as a visionary who sought to unify a fragmented Japan under a single rule. He was like a dragon with iron wings – brutal and merciless toward enemies, yet modern in thought: the first to make significant tactical use of firearms, he broke with aristocratic etiquette and surrounded himself with capable people regardless of their birth. In his shadow grew future great generals and artists – including the young Shigenari.

When Furuta Shigenari came of age, the world had already become a roaring war machine. It was the age of steel, treachery, and great ambitions. Together with other samurai from the Mino province, he swore loyalty to Oda Nobunaga – a man whose name evoked both fear and admiration. For the young warrior, it was a baptism by fire in its purest form. Participation in the campaigns against the Saitō and Asakura clans – expeditions full of blood, sweat, and mud – taught him not only how to wield a sword, but how to read an opponent’s intentions. He fought, but he was not merely a warrior – he was an observer. Amid the chaos of battle, he absorbed details: the shape of armor, the silence before an attack, the expression on the face of a dying commander.

When Furuta Shigenari came of age, the world had already become a roaring war machine. It was the age of steel, treachery, and great ambitions. Together with other samurai from the Mino province, he swore loyalty to Oda Nobunaga – a man whose name evoked both fear and admiration. For the young warrior, it was a baptism by fire in its purest form. Participation in the campaigns against the Saitō and Asakura clans – expeditions full of blood, sweat, and mud – taught him not only how to wield a sword, but how to read an opponent’s intentions. He fought, but he was not merely a warrior – he was an observer. Amid the chaos of battle, he absorbed details: the shape of armor, the silence before an attack, the expression on the face of a dying commander.

The battlefield was not the only arena of his coming-of-age. As a respected vassal, Shigenari married a woman from a powerful family – the sister of a daimyō from a neighboring province. It was a marriage like many during the Sengoku era: tactical, politically grounded, meant to tighten alliances and sever potential betrayals. Yet within those cold, diplomatic frameworks lay something delicate – access to worlds more subtle than war. In the homes of the aristocracy, where he conversed over sake, he began to hear about chanoyu – the “Way of Tea.” At first in passing. Then with curiosity. Finally – with a quiet, growing sense of wonder.

The battlefield was not the only arena of his coming-of-age. As a respected vassal, Shigenari married a woman from a powerful family – the sister of a daimyō from a neighboring province. It was a marriage like many during the Sengoku era: tactical, politically grounded, meant to tighten alliances and sever potential betrayals. Yet within those cold, diplomatic frameworks lay something delicate – access to worlds more subtle than war. In the homes of the aristocracy, where he conversed over sake, he began to hear about chanoyu – the “Way of Tea.” At first in passing. Then with curiosity. Finally – with a quiet, growing sense of wonder.

Outwardly, he was still only a warrior – a man who knew the value of a strike and the cost of an alliance. But within his soul, another kind of courage was awakening: the courage to pause, to contemplate, to find harmony in a tea bowl – something that deeply reminded him of his childhood. He was not yet a tea master. But he was a man who had understood that true strength is born not only in the fire of battle, but also in the silence of a moment, in the shadow cast by tatami, in the crack of a ceramic bowl that becomes beautiful. Thus was born his hidden passion, which would give rise to works and concepts still admired and appreciated in the 21st century.

Outwardly, he was still only a warrior – a man who knew the value of a strike and the cost of an alliance. But within his soul, another kind of courage was awakening: the courage to pause, to contemplate, to find harmony in a tea bowl – something that deeply reminded him of his childhood. He was not yet a tea master. But he was a man who had understood that true strength is born not only in the fire of battle, but also in the silence of a moment, in the shadow cast by tatami, in the crack of a ceramic bowl that becomes beautiful. Thus was born his hidden passion, which would give rise to works and concepts still admired and appreciated in the 21st century.

At Hideyoshi’s side – art becomes strategy

After the death of Nobunaga, when Japan wavered on the brink of anarchy, Furuta Shigenari did not withdraw from the game. He made a bold move – he sided with Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a brilliant commander of low birth but immense ambition (elevated by Nobunaga himself – though he called him “monkey” and simultaneously scorned him). It was at his side that Shigenari – now no longer just a samurai, but a political player – entered new campaigns, and battlefields now intertwined with castle corridors, where alongside weaponry, calligraphy, poetry, and mastery of the tea ceremony held sway. In the shadows of ornate pavilions, amid the scent of incense and the clink of tea bowls, Shigenari discovered another world – a world in which art was strategy, and silence could achieve more than a command.

After the death of Nobunaga, when Japan wavered on the brink of anarchy, Furuta Shigenari did not withdraw from the game. He made a bold move – he sided with Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a brilliant commander of low birth but immense ambition (elevated by Nobunaga himself – though he called him “monkey” and simultaneously scorned him). It was at his side that Shigenari – now no longer just a samurai, but a political player – entered new campaigns, and battlefields now intertwined with castle corridors, where alongside weaponry, calligraphy, poetry, and mastery of the tea ceremony held sway. In the shadows of ornate pavilions, amid the scent of incense and the clink of tea bowls, Shigenari discovered another world – a world in which art was strategy, and silence could achieve more than a command.

It was then that his path crossed with that of Sen no Rikyū – the greatest reformer of chanoyu (the Japanese tea ceremony), master of austere simplicity and spiritual depth. Rikyū was like a monk among generals – his tea was ascetic, nearly colorless, yet full of hidden light. Shigenari, at first merely a listener and observer, quickly became one of the master’s closest students. And though he absorbed every word with pure admiration, something within him was already rebelling. For where was the place in all this for his temperament? For distortion, provocation, drama?

It was then that his path crossed with that of Sen no Rikyū – the greatest reformer of chanoyu (the Japanese tea ceremony), master of austere simplicity and spiritual depth. Rikyū was like a monk among generals – his tea was ascetic, nearly colorless, yet full of hidden light. Shigenari, at first merely a listener and observer, quickly became one of the master’s closest students. And though he absorbed every word with pure admiration, something within him was already rebelling. For where was the place in all this for his temperament? For distortion, provocation, drama?

Under Rikyū’s guidance, he learned that chanoyu was not merely a ceremony, but a philosophy of presence – expressed in every gesture, in silence, in the choice of a bowl, in a subtle bow, in the way water steams in a kettle. But he also learned that it was theatre. That guest and host played roles. And perhaps that was what ignited his passion for a different approach. Instead of austere greys – green glazes. Instead of balance – a tilt. Instead of predictability – asymmetry, dynamism, and deformation that stirs the soul. Thus was born what would later be called Oribe no bi – the aesthetics of Furuta Oribe. Beauty twisted, but sincere. Tea bowls of distorted shapes, as if they had passed through a storm – and emerged more beautiful for it.

Yet within his soul, two elements clashed. On one hand – the warrior. A man who knew the weight of a sword and could give a command that ended a life. On the other – the artist. The host of a ceremony who could scatter pine needles in a garden to evoke springtime in the heart of winter. Can one be both the killer and the contemplator of a steaming tea bowl? Is chanoyu an escape – or a new battlefield, though internal?

Yet within his soul, two elements clashed. On one hand – the warrior. A man who knew the weight of a sword and could give a command that ended a life. On the other – the artist. The host of a ceremony who could scatter pine needles in a garden to evoke springtime in the heart of winter. Can one be both the killer and the contemplator of a steaming tea bowl? Is chanoyu an escape – or a new battlefield, though internal?

Shigenari – who was slowly becoming Oribe – knew that one side could not be abandoned. His art was born not in spite of this conflict, but because of it. In the tension between steel and ceramics, between blood and incense, between screams of agony and the silence of a garden – he forged his path. He was no longer just a student of Rikyū. He was one who had taken the master’s fire – and cast it into the kiln of his own twisted vision of beauty.

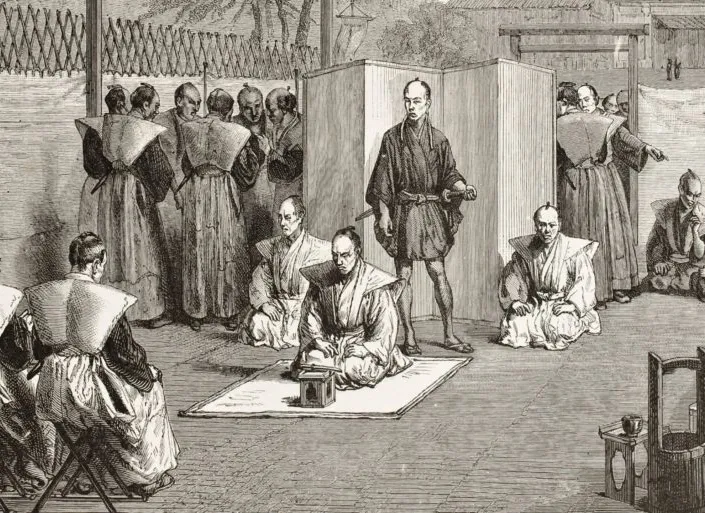

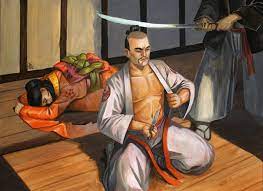

After the master’s death – the birth of Oribe the artist

The year was 1591. By order of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Sen no Rikyū, the greatest tea master of the age, was forced to commit seppuku (for an explanation of samurai ritual suicide, see: Samurai Seppuku: Ritual Suicide in the Name of Honor, or Bloody Belly Cutting and Hours of Agony?). The silence after his death was like a tear in velvet – something extraordinary had vanished from the landscape of Japanese culture. For Furuta Shigenari – by then already bearing the title Oribe – it was a deeply personal blow. He had been not only Rikyū’s student but one of the few who dared visit the master in his final days of seclusion, risking everything. Now he was alone. And yet – as if from that void, from the grief of losing his teacher – something new began to take root. When Rikyū’s flame was extinguished, Oribe seized the torch and walked his own path. Not in the shadow, but against the wind.

The year was 1591. By order of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Sen no Rikyū, the greatest tea master of the age, was forced to commit seppuku (for an explanation of samurai ritual suicide, see: Samurai Seppuku: Ritual Suicide in the Name of Honor, or Bloody Belly Cutting and Hours of Agony?). The silence after his death was like a tear in velvet – something extraordinary had vanished from the landscape of Japanese culture. For Furuta Shigenari – by then already bearing the title Oribe – it was a deeply personal blow. He had been not only Rikyū’s student but one of the few who dared visit the master in his final days of seclusion, risking everything. Now he was alone. And yet – as if from that void, from the grief of losing his teacher – something new began to take root. When Rikyū’s flame was extinguished, Oribe seized the torch and walked his own path. Not in the shadow, but against the wind.

This was the moment the artist was born. And a radical artist at that. Oribe did not merely continue wabi-sabi – he challenged it. His ceramics – Oribe-yaki – were like a scream in the silence: deformed shapes, asymmetry, violent lines, glazes of vivid copper green, deep black, and white cut with grotesque patterns. Where Rikyū sought silence, Oribe gave voice to the noise of a soul raised in the bloody chaos of war. His tea bowls were not vessels – they were personalities. They carried echoes of kabuki theatre, tales straddling dream and wakefulness, carnality and extravagance. It was no accident they were called “bizarre” – and that was exactly what Oribe wanted. In art, he saw not only contemplation, but provocation. It was not beauty for beauty’s sake – it was about truth, and truth is never smooth.

This was the moment the artist was born. And a radical artist at that. Oribe did not merely continue wabi-sabi – he challenged it. His ceramics – Oribe-yaki – were like a scream in the silence: deformed shapes, asymmetry, violent lines, glazes of vivid copper green, deep black, and white cut with grotesque patterns. Where Rikyū sought silence, Oribe gave voice to the noise of a soul raised in the bloody chaos of war. His tea bowls were not vessels – they were personalities. They carried echoes of kabuki theatre, tales straddling dream and wakefulness, carnality and extravagance. It was no accident they were called “bizarre” – and that was exactly what Oribe wanted. In art, he saw not only contemplation, but provocation. It was not beauty for beauty’s sake – it was about truth, and truth is never smooth.

In time, Oribe gave the tea ceremony a new direction – bukechadō, the “Way of Tea for warriors.” It was more monumental, more hierarchical, more spatial. Where Rikyū’s tea hut was the humble cell of a hermit, Oribe introduced sliding walls, wide windows, and symbolic divisions among guests. Light entered the interior, creating dramatic tension. Shadow and brightness – like the two sides of a warrior’s soul. In this new version of chanoyu, spirituality was not neglected, but joined with prestige and politics. The ceremony became a stage for diplomacy – the tea master not only prepared matcha, but also directed the narrative, the tactics, the gesture.

In time, Oribe gave the tea ceremony a new direction – bukechadō, the “Way of Tea for warriors.” It was more monumental, more hierarchical, more spatial. Where Rikyū’s tea hut was the humble cell of a hermit, Oribe introduced sliding walls, wide windows, and symbolic divisions among guests. Light entered the interior, creating dramatic tension. Shadow and brightness – like the two sides of a warrior’s soul. In this new version of chanoyu, spirituality was not neglected, but joined with prestige and politics. The ceremony became a stage for diplomacy – the tea master not only prepared matcha, but also directed the narrative, the tactics, the gesture.

At the heart of this revolution matured Oribe’s own philosophy: “deformation leads to truth.” Only what is imperfect has the power to evoke a reaction. Only asymmetry stirs the imagination. For him, beauty was something to be fought for – like great ideals that require crossing a battlefield strewn with corpses. For was that not his Japan? Torn by war, yet still capable of creating the purest things. In his tea bowls, there was no escape from the world – there was its essence. And that is what made Oribe the greatest after Rikyū. Not because he followed the same path – but because he had the courage to turn aside.

At the heart of this revolution matured Oribe’s own philosophy: “deformation leads to truth.” Only what is imperfect has the power to evoke a reaction. Only asymmetry stirs the imagination. For him, beauty was something to be fought for – like great ideals that require crossing a battlefield strewn with corpses. For was that not his Japan? Torn by war, yet still capable of creating the purest things. In his tea bowls, there was no escape from the world – there was its essence. And that is what made Oribe the greatest after Rikyū. Not because he followed the same path – but because he had the courage to turn aside.

In the circle of the future shōgun Tokugawa – betrayal and death

At the beginning of the 17th century, Furuta Oribe stood at the height of his glory. After the death of Hideyoshi and Ieyasu’s victory at Sekigahara, Japan came under the rule of a new regime – the Tokugawa shogunate. Power stabilized, chaos subsided, and warriors began to hang their swords on the walls of pavilions. Furuta – now the official go-no chajin, the tea master of the Tokugawa Hidetada court, second shōgun of the dynasty – had everything: prestige, influence, students, the reputation of an aesthetic innovator. But this was no longer the era of Nobunaga. Nor of Hideyoshi. It was a new Japan: cold, rational, regulated – and distrustful of those who think too loudly.

At the beginning of the 17th century, Furuta Oribe stood at the height of his glory. After the death of Hideyoshi and Ieyasu’s victory at Sekigahara, Japan came under the rule of a new regime – the Tokugawa shogunate. Power stabilized, chaos subsided, and warriors began to hang their swords on the walls of pavilions. Furuta – now the official go-no chajin, the tea master of the Tokugawa Hidetada court, second shōgun of the dynasty – had everything: prestige, influence, students, the reputation of an aesthetic innovator. But this was no longer the era of Nobunaga. Nor of Hideyoshi. It was a new Japan: cold, rational, regulated – and distrustful of those who think too loudly.

And Oribe thought. And created. But his work did not fit the new aesthetics of the court. The Tokugawa loved order, harmony, precision – and his tea bowls were bizarre, wild, provocative. Where Rikyū embodied modesty, Oribe pulsed with the sensuality of form. Where the Tokugawa court was dominated by monochromatic elegance, Oribe introduced vibrant color, randomness, asymmetry, and challenge. His aesthetics were like a final cry of freedom in a country that had just begun to build walls around itself. And perhaps it was precisely that which made him great that also made him dangerous.

And Oribe thought. And created. But his work did not fit the new aesthetics of the court. The Tokugawa loved order, harmony, precision – and his tea bowls were bizarre, wild, provocative. Where Rikyū embodied modesty, Oribe pulsed with the sensuality of form. Where the Tokugawa court was dominated by monochromatic elegance, Oribe introduced vibrant color, randomness, asymmetry, and challenge. His aesthetics were like a final cry of freedom in a country that had just begun to build walls around itself. And perhaps it was precisely that which made him great that also made him dangerous.

The atmosphere began to thicken. The year was 1615 – the Siege of Osaka Castle, the final act in the Toyotomi clan’s resistance against the shogunate. Amidst plots, denunciations, and uncertain loyalties, Oribe’s name appeared. Suspicions. Whispers. It was said he sympathized with Toyotomi Hideyori, that he had contact with someone who had contact with someone… There was no hard evidence, but in an era when words were weapons, that was enough. Someone may have framed him. Someone may have wanted him gone. Or perhaps, deep down, he truly could not come to terms with the fall of the world to which he had belonged.

The atmosphere began to thicken. The year was 1615 – the Siege of Osaka Castle, the final act in the Toyotomi clan’s resistance against the shogunate. Amidst plots, denunciations, and uncertain loyalties, Oribe’s name appeared. Suspicions. Whispers. It was said he sympathized with Toyotomi Hideyori, that he had contact with someone who had contact with someone… There was no hard evidence, but in an era when words were weapons, that was enough. Someone may have framed him. Someone may have wanted him gone. Or perhaps, deep down, he truly could not come to terms with the fall of the world to which he had belonged.

Rumors of treason reached the shōgun. Furuta Oribe was ordered to commit seppuku. And he did. Without protest. Without a word. Without a manifesto written in calligraphy, as many samurai did. His death was like his tea bowl – deformed, but true. The silence he left behind was the deepest of his works. Was he guilty of betraying the shogunate? History does not provide a clear answer. But his death marked the end of an era – the end of an artist who did not fit into the smooth frame of the new order.

Rumors of treason reached the shōgun. Furuta Oribe was ordered to commit seppuku. And he did. Without protest. Without a word. Without a manifesto written in calligraphy, as many samurai did. His death was like his tea bowl – deformed, but true. The silence he left behind was the deepest of his works. Was he guilty of betraying the shogunate? History does not provide a clear answer. But his death marked the end of an era – the end of an artist who did not fit into the smooth frame of the new order.

Thus departed Furuta Oribe – master of defiant aesthetics, a samurai who dared to create an ugliness more beautiful than beauty itself. And perhaps that is why he had to fall silent. But his silence still resonates in tea bowls that remind us that art has the right to “act out” even when the world demands order.

The aesthetics of Oribe, which endure to this day

Although the story of Furuta Oribe ends in silence beneath the castle walls of Edo, his art is still recognized today. Not only because he was the creator of a bold and original aesthetic (Oribe no bi) – but because he gave Japanese ceramics an entirely new language. In a time when clay was mainly a medium of humility, he made it a vehicle for unrest, defiance, and unconventional beauty. His greatest legacy is the vessels that still bear his name: Oribe-yaki (織部焼) – Oribe ware.

Although the story of Furuta Oribe ends in silence beneath the castle walls of Edo, his art is still recognized today. Not only because he was the creator of a bold and original aesthetic (Oribe no bi) – but because he gave Japanese ceramics an entirely new language. In a time when clay was mainly a medium of humility, he made it a vehicle for unrest, defiance, and unconventional beauty. His greatest legacy is the vessels that still bear his name: Oribe-yaki (織部焼) – Oribe ware.

What makes these vessels exceptional is not only the famous green glaze based on copper oxide, though that is what posterity remembers most vividly. It is also the contrast with the muted white glaze, the graphite drawings depicting landscapes, fences, geometric patterns, birds, pavilions, sometimes even human figures – as if the bowl were a small scroll painting to be viewed in the hands. Oribe was a pioneer in combining painted designs with spatial deformation – his vessels were often deliberately tilted, irregular, as though formed by accident, even though every detail was intentional. The departure from symmetry was no accident – it was a program. Many Oribe bowls resemble landscapes painted in clay – mountains and valleys of form, roughness, granularity, elevations and folds that evoke Japan’s untamed nature.

The primary center of production became Mino (present-day Gifu Prefecture) – it was there that the famous tile kilns were located, where Oribe worked with potters, experimenting with form and firing techniques. It was in Mino that a lesser-known but captivating variation was also born: Kuro-Oribe – black Oribe ware, coated in a thick glaze, with abstract, calligraphy-like brushwork. There was also Ao-Oribe – dominated by blues and greens – and Narumi-Oribe, combining colors and patterns into complex, rhythmic compositions.

The primary center of production became Mino (present-day Gifu Prefecture) – it was there that the famous tile kilns were located, where Oribe worked with potters, experimenting with form and firing techniques. It was in Mino that a lesser-known but captivating variation was also born: Kuro-Oribe – black Oribe ware, coated in a thick glaze, with abstract, calligraphy-like brushwork. There was also Ao-Oribe – dominated by blues and greens – and Narumi-Oribe, combining colors and patterns into complex, rhythmic compositions.

Oribe was also the one who introduced new forms of utensils into chanoyu – his tea bowls were taller, more slanted; teapots had pointed spouts, and incense bowls resembled sculptures. Even flower vases (hanaire) in his style seem to have character – like the faces of old men, full of wrinkles, irregularities, and melancholy. Oribe’s aesthetics also influenced the architecture of tea pavilions – he experimented with asymmetrical tatami layouts, unusual tokonoma arrangements, and irregularly shaped doors and windows.

All of this creates a vision of art that does not soothe – but stimulates. That does not mold the world into an ideal – but teaches how to see unconventional beauty in the world. In this sense, Oribe was a revolutionary: not so much against the political system as against aesthetic dogma. Where others sought harmony – he chose tension. Where others said “yes” to tradition – he asked “why?”. That is why his tea bowl is more a state of mind, and his style remains easily recognizable to this day.

All of this creates a vision of art that does not soothe – but stimulates. That does not mold the world into an ideal – but teaches how to see unconventional beauty in the world. In this sense, Oribe was a revolutionary: not so much against the political system as against aesthetic dogma. Where others sought harmony – he chose tension. Where others said “yes” to tradition – he asked “why?”. That is why his tea bowl is more a state of mind, and his style remains easily recognizable to this day.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Japanese Karesansui Garden is a Mirror in Which You Can See Yourself

Turn off the world. Step into the water. Furo

The Tokugawa Shōgunate After the Fall of Samurai Japan – How They Survived the 20th Century and What They Do Today?

Iemoto – The Japanese Master-Disciple System That Has Endured Since the Shogunate Era

Iwasaki vs. Golden: A Battle for the Honor of Japanese Geisha Traditions