Iwasaki vs. Golden: A Battle for the Honor of Japanese Geisha Traditions

The Cruel Irony of Fate

(The following article focuses on the dispute between Iwasaki and Golden—if you wish to learn more about Mineko Iwasaki's life and work, I invite you to read the article dedicated to her story: She Taught Us What the Life of Japanese Geishas Truly Is: The Story of Mineko Iwasaki).

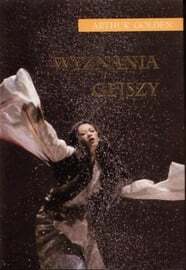

Memoirs of a Geisha

The process of creating this book was far from a typical literary endeavor. Golden approached the subject with near-journalistic thoroughness, conducting numerous interviews with people connected to the world of geisha, including Mineko Iwasaki, one of the most renowned figures of the profession. Lured by promises of discretion and a vision of representing geisha in a respectful and authentic manner, Iwasaki opened the doors to a world whose secrets had been tightly guarded. Golden stayed at her home for two weeks, gathering detailed information about the lives, rituals, and daily routines of geisha. These materials became the backbone of his book, although—as it turned out later—in a way that diverged significantly from Iwasaki's intentions.

The Conflict Between Golden and Iwasaki

When Iwasaki received translations of the book, her anger turned to shock. Golden described mizuage, the ceremony marking a maiko’s transition to a geiko, as an auction of young women’s virginity. In the novel, Sayuri, the protagonist, achieves the status of geisha after her virginity is sold to the highest bidder. Iwasaki, who had spent years fighting against Western stereotypes, realized that her name—and the entire world of geisha—had become entangled with an image drawn directly from Western erotic fantasy, painfully distant from Japanese realities. In her experience, mizuage was a symbol of maturation and transition to adulthood, not a transaction involving the sale of one’s body. For Iwasaki, this depiction was a betrayal—not only of her but also of the culture she had long represented.

As Memoirs of a Geisha gained popularity and Golden spoke about his collaboration with Iwasaki in interviews, the tension grew. For many Western readers, geisha became exotic courtesans—sophisticated but still subordinated to male sexual desire. Mineko, whose life had been a testament to geisha as artists and cultural guardians, could not tolerate this narrative. In 2001, after years of internal turmoil, she decided to act. She filed a lawsuit against Golden and his publisher, Random House, accusing them of breach of contract, defamation, and unauthorized use of her life story. “It’s not about money,” she said in interviews. “It’s about honor.”

In a 2001 interview with The Japan Times, Iwasaki said:

Her words emphasize how essential it was for her to restore the truth about geisha culture and protect it from false stereotypes.

Golden and his publisher vehemently denied the allegations. They claimed there was no written agreement guaranteeing anonymity and asserted that Iwasaki had initially been pleased to be credited for her contributions. "It was difficult to keep up with her wishes," Golden explained. The dispute delved into deeply personal matters of dignity and truth within the geisha community. What was mere literary fiction for Golden was, for Iwasaki, a lie directly undermining everything she had fought for in her life—a lie signed with her name.

The Course of the Dispute

Golden and his publisher denied the accusations, arguing that no formal, written agreement on anonymity existed. They emphasized that Iwasaki had initially been pleased to be acknowledged for her inspiration for the book. Golden repeatedly stated in interviews that Sayuri’s story was a composite of interviews with several geisha, not solely Iwasaki’s account. He also maintained that the book was purely a work of fiction, not a historical document.

The trial attracted global media attention, highlighting cultural differences in how geisha were perceived and raising questions about authors’ responsibilities in portraying foreign traditions. Iwasaki received support from those who saw her actions as an effort to protect Japanese tradition from Western distortion. On the other hand, Golden and his publisher defended their right to artistic interpretation, arguing that the book was never intended to be perceived as an accurate representation of reality.

In 2003, the case was ultimately settled out of court. The details of the settlement were never made public, a common practice in such cases. However, it is known that Random House agreed to a financial settlement for Iwasaki. Importantly, her name was removed from the Japanese edition of the book, which was one of the lawsuit’s central demands.

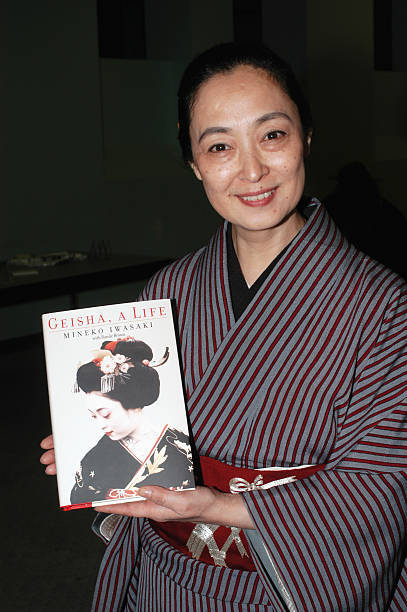

The conflict between Golden and Iwasaki extended far beyond the courtroom. It sparked a global conversation about authors’ responsibilities in depicting other cultures and the boundaries between creative freedom and the need for authenticity. Iwasaki used this dispute as the impetus to write her own autobiography, Geisha, a Life, which served as her rebuttal to the oversimplifications and inaccuracies of Golden’s novel. For her, this was not merely a form of defense but also an attempt to portray the true life of a geisha and preserve their legacy from distortion.

Differences in Golden’s and Iwasaki’s Depictions of the Geisha World

The contrast between Arthur Golden’s Memoirs of a Geisha and Mineko Iwasaki’s Geisha, a Life reveals fundamental differences in how the life of a geisha is portrayed. Golden, drawing on interviews and his own interpretations, crafted a fictional narrative that, while colorful and engaging, deviates significantly from the reality described by Iwasaki. Her autobiography was almost a direct response to the simplifications and inaccuracies in the American author’s bestseller.

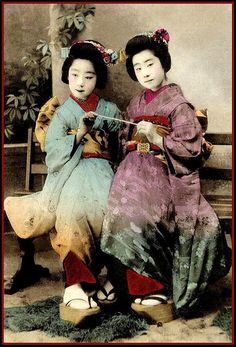

Mizuage (水揚げ – "Rising Water Surface")

Mizuage (水揚げ – "Rising Water Surface")

One of the most controversial issues was the depiction of mizuage. In Memoirs of a Geisha, it is a dramatic turning point—the protagonist Sayuri attains the status of geisha after her virginity is auctioned to the highest bidder. Golden portrays this ritual as an intensely sexual experience, depicting geisha as women involved in the trade of their bodies.

Iwasaki, in her book, vehemently denies this interpretation. According to her, mizuage was a symbolic ritual signifying a maiko’s transition to geiko. She emphasizes that the ceremony had no sexual connotations and that equating it with a virginity auction stems from confusing geisha traditions with the practices of oiran—luxury courtesans from Japan’s entertainment districts (check our article about Oiran here: Oiran - The Highest Courtesan and Master of Art with the Entertaining Escort of Geisha: A Story Misunderstood in the West).

The Role of Geisha: Artist or Courtesan?

In her autobiography, Iwasaki counters this portrayal with a vision of geisha as artists whose lives revolve around mastering traditional Japanese arts, such as dance, playing the shamisen, and the tea ceremony. She stresses that geisha in Gion did not "sell their bodies" but rather their artistic and intellectual skills. She writes, "It was a world founded on discipline, beauty, and respect—not desire." Her descriptions highlight geisha as guardians of tradition and culture rather than sexual objects.

Hierarchies and Relationships in the Geisha House

Iwasaki, in Geisha, a Life, presents the okiya as spaces of strict discipline but also mutual support and respect. She emphasizes that while relationships between the women were challenging, physical violence was unacceptable as it could harm their artistic abilities. Iwasaki describes her life in the Iwasaki house as full of challenges but also rich with opportunities for growth and learning.

Clients: Families or Suitors?

In contrast, Iwasaki underscores in her autobiography that geisha often built relationships with entire families. She recounts instances where men would bring their wives and children to the ochaya to admire geisha performances. Her stories depict a world where geisha were integral to broader social life, not merely an exclusive indulgence for men.

Narrative Style: Fiction Versus Autobiography

The conflict between these books represents a clash of two visions: Golden’s colorful but oversimplified literary fiction and Iwasaki’s precise, balanced autobiography.

Geisha Life in Ochaya

Mineko Iwasaki, in her autobiography, portrays ochaya in a completely different light. She describes tea houses as spaces of art and ceremony, where geisha could fully showcase their skills. Although competition existed and was strict, it was healthy and motivating rather than destructive. For example, Iwasaki recalls how senior geisha supported younger ones by helping them develop their talents and sharing their knowledge. Her account lacks the dramatic conflicts but emphasizes fair and disciplined collaboration.

Mentorship and Apprentice Relationships

Iwasaki highlights the unique bonds between apprentices and their mentors. She recounts how her mentor not only taught her artistic crafts but also provided emotional and moral support. These relationships were characterized by mutual respect and loyalty, essential elements of life in the geisha world. Rather than rivals or adversaries, mentors were seen as protectors who guided their apprentices toward perfection.

Understanding Beauty and Tradition

Iwasaki stresses that beauty in the geisha world held a deeper significance—it reflected inner harmony and dedication to tradition. She describes how learning dance or playing the shamisen was not just a way to hone artistic skills but also a spiritual journey. In her book, geisha beauty is not merely a visual effect but a culmination of aesthetic values, discipline, and harmony.

Perceptions of Danna—the Geisha Sponsor

Iwasaki dismantles this myth, asserting that in reality, many geisha, including herself, never had a danna. She emphasizes that geisha were independent artists who did not need sponsors to succeed. In her autobiography, she writes that geisha in Gion took pride in their autonomy and often avoided relationships that could harm their reputation as professionals.

The Career of a Geisha

Golden depicts the life of a geisha as a series of dramatic highs and lows, where every step up the social ladder comes with personal sacrifices and scandals. In his novel, geisha are portrayed as individuals constantly fighting for survival in a brutal and unforgiving world.

Iwasaki offers a contrasting perspective on life as a geisha—a journey filled with hard work but also artistic fulfillment. She recounts performances that brought her joy and satisfaction, as well as the relationships she built with clients and colleagues. Her descriptions of geisha life are more balanced and realistic, highlighting both the challenges and the beauty of the profession.

Somber Reflections

Golden and Iwasaki’s story fits seamlessly into the broader context of the West’s orientalist approach to the East, as described by Edward Said. Memoirs of a Geisha is a product of a Western gaze on the East—rich in exoticism but tinted with stereotypes and fantasies. Golden, while undoubtedly fascinated by Japanese culture, fell into the trap of orientalism, crafting a vision of geisha as almost mythical figures, yet entwined in a world of sexual desire. For Iwasaki—a woman raised in the spirit of Japanese tradition—this was a betrayal of the culture to which she had devoted her entire life.

Ultimately, the issue of artistic responsibility remains: Where is the line between interpretation and exploitation? Golden and Iwasaki’s story serves as a reminder that creating art based on cultures other than one’s own requires more than fascination or admiration. It demands respect, deep sensitivity, and a willingness to give voice to those who have lived these stories. This is a lesson for writers, artists, and anyone who seeks to tell the stories of others—to remember that cultural authenticity is not merely an embellishment for a narrative but its foundation.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

She Taught Us What the Life of Japanese Geishas Truly Is: The Story of Mineko Iwasaki

Women of the Yakuza – Silently Bearing the Scars on Their Bodies and Hearts

The Female Samurai Unit Jōshitai – The Ultimate Determination of Fighting Mothers and Sisters

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Mizuage (水揚げ – "Rising Water Surface")

Mizuage (水揚げ – "Rising Water Surface")