Close the World Behind the Door. Tokonoma – The Japanese Art of Emptiness in Your Home

A Stem, a Shell, and a Calligraphy Scroll

In 2017, environmental psychologist Kazuhiro Nakamura studied the impact of such silence on the nervous systems of residents in micro-apartments in Tōkyō. Among those who contemplated a simple tokonoma composition for a few minutes daily, a 16% lower rate of autonomic tension was recorded compared to those without such a space. No incense, no mantra—just the pause. And it is in this pause that the essence of the Japanese concept of ma (間) lies—the space between things that does not divide, but gives meaning. The empty alcove is not about decoration—tokonoma teaches us attentiveness. It teaches that a leaf in a vase may wilt sooner than we find the time to pause and appreciate its beauty, even once. The same applies to life as a whole. Tokonoma teaches that every thing—and every moment—passes. Without attentiveness, we are merely sleepwalkers who are suddenly born and suddenly die, with nothing in between that we managed to… notice.

In today’s article, we will explore what a Japanese tokonoma is, what role it plays in the lives of Japanese people, what its history and meaning are—and how to build one even in our Polish homes. Let’s begin!

The Kanji 床の間 (tokonoma) and Its Meanings

The character 床 (toko) is most commonly associated with the floor, a bed, a place where the body rests. It is ground—but not geological ground; rather, a base, a background, a foundation of existence. A Japanese home knew no beds or sofas; it knew tatami mats, upon which one sits, sleeps, meditates.

And finally—ma (間), the key character of Japanese aesthetics. It can be translated as “interval,” “pause,” “in-between,” but most importantly—as “meaningful space” (we write more about it in the article on ikebana: Ikebana: The Japanese Art of Speaking in Flowers). In writing, it consists of a gate (門) through which light passes (日 – the sun). Ma is not simply “between this and that,” but a space that in itself carries meaning (in Japan, empty space often holds more meaning than the things it separates). A void that is not emptiness, but potential. Silence that is not the absence of sound, but its fullness. In tokonoma, ma is precisely that subtle space—the meeting place of the eye and the image, the heart and time, the mind and the pause. Tokonoma is thus not just a niche. It is a symbolic frame made of three characters: ground (toko), relationship (no), and meaningful space (ma). One could say: it is a physical place where the spirit may sit down.

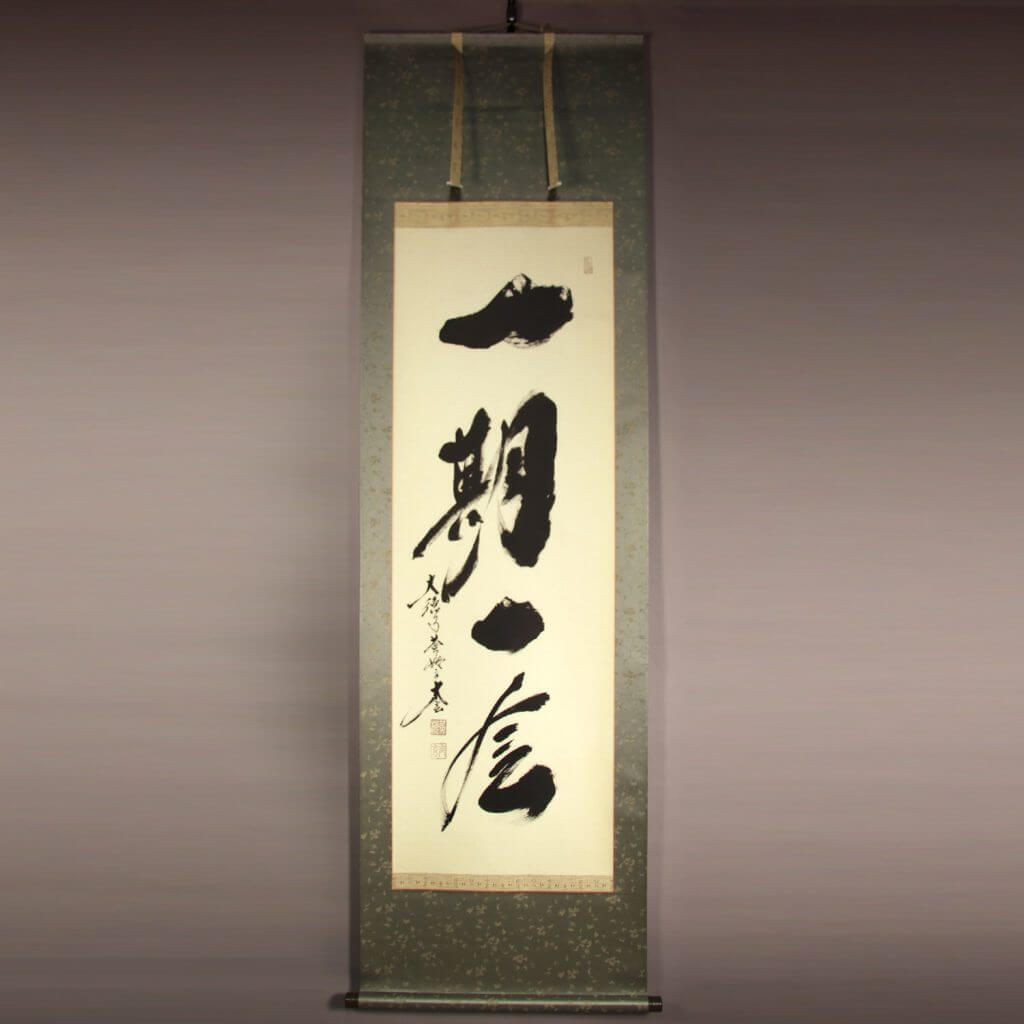

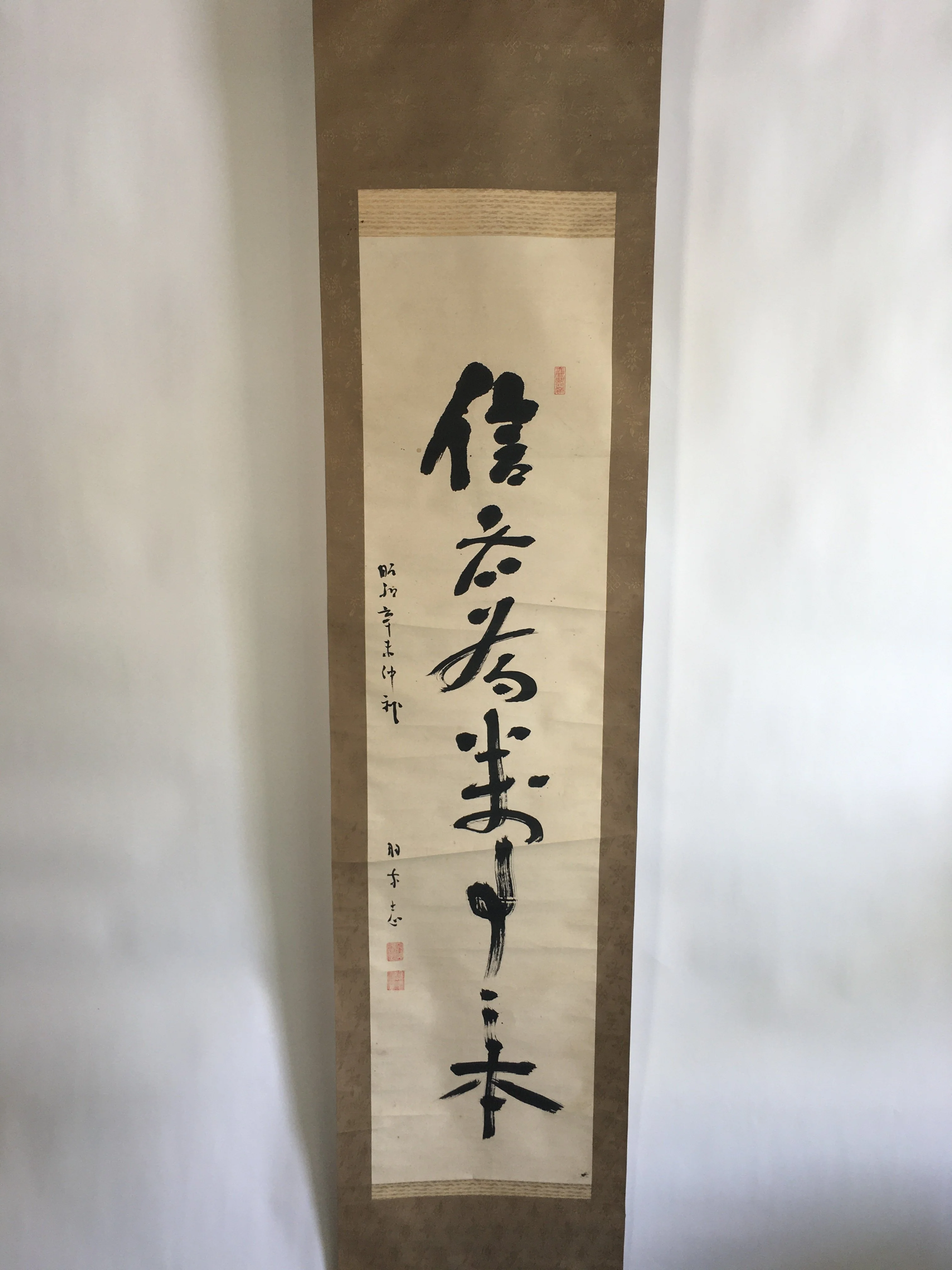

It is worth mentioning concepts that grow from this same aesthetic. Chigaidana—asymmetrical shelves that sometimes appear next to the tokonoma—operate under the principle of fūga—elegance through irregularity. Kakemono, the scroll hanging in the niche, is not a decoration but the voice of the moment—often a calligraphy of a single character that serves as a philosophical echo of, for instance, the season (of which there are 72 in a year—we write more about that here: The 72 Japanese Seasons, Part 1 – Spring and Summer in the Calendar of Subtle Mindfulness). Toko-bashira, the vertical post of the tokonoma, is sometimes made of unhewn wood—as if nature were allowed inside to look at us, not just be looked at. Zashiki and washitsu—traditional rooms—are spaces that are born around the tokonoma, not the other way around. Tokonoma is not an addition to the home. The rooms around it are the addition to it.

In this one word: 床の間—we can glimpse a Japanese lesson in presence. Seek not content in the object, but in the space around it. Not in the sound, but in the silence that follows. Not in the story, but in the pause between words. Not in the rooms of the inhabitants, but in the interval between them.

A Scene by the Tokonoma

The washitsu holds merely three tatami, arranged in a goza layout—one perpendicular to the other, the third by the entrance. On the right side, vis-à-vis the low zabuton cushion, a pine-carved niche—tokonoma. Its sugi (杉 – Japanese cryptomeria, mistakenly called cedar) frames retain discreet cracks and lighter resin streaks; the wood makes no pretense of perfection. The alcove floor is covered with a darker, almost brownish-green mat—slightly deeper in tone than the rest—a small difference, but noticeable to the eye.

There is nothing religious or ceremonial here. No ritual that requires kneeling or reciting. Only a conscious pause.

The tokonoma reminds her that the season is stirring—quietly, yet inexorably. That today’s “self” will soon become yesterday’s “someone.” That the branch needs water and attention, but not words, not worries.

The minutes pass without haste. Outside the window, the lanterns of Kaigan-dōri begin to glow, and the green-and-cream Hakodate City Tram, line no. 2, screeches along the curve by Ōmachi-teiryūjō stop. Sayaka finishes her tea, gently sets the cup down on the edge of the mat. She moves nothing—not the slender branch, nor her own thoughts. The emptiness seems tailored to her measure: neither too narrow, nor overwhelming. A space that serves no purpose—simply persists, and allows her to persist without purpose—however long Sayaka may desire. And perhaps it is precisely because of this that, although the night thickens beyond the glass, the little apartment becomes just a touch brighter.

The History of Tokonoma – Origins in the Chaos of the Sengoku Wars

With time, the tokonoma detached itself from the sacred—at least formally. But it still retained its afterglow. It transformed into ma—the space between. Not in the sense of emptiness, but of pause. It is not a wall. Not a decoration. The tokonoma was not created to store anything, but to experience something—without touching, without taking, without commenting. Simply to be. And in this sense, though born in feudal times, the tokonoma speaks to the 21st-century human in a language we still need: the language of attentiveness, silence, and conscious observation.

Tokonoma Through the Ages of Japanese History

The Late Middle Ages: Azuchi-Momoyama (1573–1603)

In the Azuchi-Momoyama period—a time of great political change and power consolidation by Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi (more on this here: What Does “Shōgun” Really Mean? One word that forged the Japan of samurai in steel and blood)—the tokonoma gained a more monumental and expressive character, particularly in the residences of daimyō and the warrior aristocracy. In the palaces and villas of the elite, designed among others by the masters of the Kanō school, the tokonoma took on a representational role: it was wider, often composed of multiple levels (e.g., separate spaces for the scroll, for the byōbu screen, or for flowers), and its background was adorned with richly colored paintings, often depicting landscapes, Chinese motifs, or symbols of strength and dignity. It was, in a sense, the Japanese “Baroque.”

In styles such as shoin-zukuri, developed in this era to an almost classical form, the tokonoma was an integral part of the zashiki—the formal guest room—and acquired its standard elements: a scroll (kakemono), a floral composition (chabana or ikebana), and a carefully selected vessel (usually ceramic or lacquered wood). At the same time, attention began to be paid to the quality of the toko-bashira (corner post), choosing wood with distinctive grain patterns or curves that expressed “wild beauty.”

The Tokugawa Shogunate: Edo Period (1603–1868)

The Tokugawa Shogunate: Edo Period (1603–1868)

During the Edo period, the tokonoma became standardized as an almost obligatory element of every formal zashiki—not only in samurai residences but also in wealthier merchant homes. Urban architecture, especially in Edo (modern-day Tokyo), Ōsaka, and Kyōto, popularized interiors with clearly defined layouts: the tokonoma as the compositional axis of the room, placed opposite the entrance or in a corner.

Aesthetic norms for the tokonoma emerged, regulating not only its size but also its proportions in relation to the other elements of the room. The scroll and floral composition became tools for expressing the host’s taste and erudition—especially during social gatherings, tea ceremonies, or New Year visits. In sukiya-zukuri architecture, inspired by the philosophy of wabi-cha, the tokonoma took on a more modest, intimate form: often very shallow, with a natural, unfinished toko-bashira (e.g., made of sugi or bamboo).

Modernity: Meiji (1868–1912) and Taishō (1912–1926)

On the other hand, during the era of national modernization, the tokonoma acquired a new, symbolic function—as a sign of traditional identity and spiritual heritage. In the villas of the political or artistic elite, a washitsu with a tokonoma was often deliberately designed as a declaration of attachment to the aesthetics and ethos of pre-modern Japan.

Contemporary Times: Shōwa (1926–1989), Heisei (1989–2019), and Reiwa (2019–?)

However, from the 1980s onward, a certain revival can be observed: in single-family homes—especially wa-yō-setchū, which blend Western and Japanese styles—it became increasingly common to include one traditional-style room, typically with a miniature tokonoma, treated as a conscious aesthetic choice, a place for focus, tranquility, and a symbolic “return to roots.”

In the Heisei era, and especially now in Reiwa, tokonoma have once again begun to appear more frequently: in more traditional homes, in ryōkan (Japanese inns), tea houses, occasionally in artistic spaces or rooms designed in the spirit of chashitsu, and even—in modern residential construction. Contemporary tokonoma are often minimalist, frequently reinterpreted: made of glass, concrete, betsu-no-ma with LED lighting or with steel toko-bashira. Yet the idea remains unchanged—it is a space that serves not a practical function, but a symbolic one: attentiveness, seasonal rhythm, and reverence for impermanence.

The Role of the Tokonoma Alcove in Life

What does literature say?

What does literature say?

(yohaku no bi – 余白の美 – the beauty of empty white space)

When we enter a traditional washitsu, the eye almost instantly halts at the carved-out space in the wall—the tokonoma. This pause in the material, so characteristic of Japanese spatial culture, is not a decoration; it is the embodiment of ma (間)—an interval that becomes content, although it contains no “object” in itself. Architect Arata Isozaki wrote that ma is “the body of time,” but in the alcove, that time has taken the shape of silence.

“What is essential is better said briefly—or not at all.”

—Sen no Rikyū, Nanporoku

The Japanese notion of yohaku no bi (余白の美)—the beauty of a left-behind margin (white space)—rests on the belief that what is absent creates balance for what is present. Philosopher and art historian Yanagi Sōetsu saw in the emptiness of the alcove an “intentional silence,” without which it is impossible to hear the subtle nuances—of the world and of one’s own thoughts. This interior silence was sometimes even a meditative practice: monk Takuan Sōhō advised his zen students to gaze at the empty wall of the alcove in order to “air out the mind’s eye”—just as one cleanses a brush before dipping it in ink.

What does science say?

Environmental psychologist Kazuhiro Nakamura (2017) measured heart rate variability in residents of micro-apartments in Tōkyō. Among participants who spent a few minutes each day gazing at a simple tokonoma composition, vegetative tension levels were found to be up to 16% lower than in the control group, which lacked any form of “organized emptiness.” No scented candles, no mantras—only the pause.

“Ma” Speaks More

This is why contemporary interior designer Shigemori Masaaki suggests that when planning a small apartment, one should “reserve at least one place that will remain empty.” The tokonoma, even a symbolic one with a single modest scroll, is now more a psychological practice than a decoration. It serves no purpose—and therein lies its greatest power.

Can You Create a Tokonoma at Home—Here in Poland?

Can You Create a Tokonoma at Home—Here in Poland?

The tokonoma alcove is not a piece of furniture or decoration. It is a symbolic space—a zone of focus and observation, exempt from the rule of utility. In traditional Japanese homes, the tokonoma is a small alcove in the zashiki (guest room), where carefully chosen elements are placed: a scroll, a plant, and an object. Their changeability resonates with the rhythm of the seasons, and their presence serves as an invitation to pause and contemplate. This same idea can be brought into a modern apartment—adapted to local materials, lighting conditions, and one’s own way of life.

Dimensions and Proportions

Dimensions and Proportions

A traditional tokonoma is not large—it often occupies a space roughly the size of one tatami mat (about 90 x 180 cm) and has a depth ranging from 30 to 60 cm. However, proportions are more important than size. The key principle is asymmetry and unbalanced harmony—the scroll should hang slightly off-center, the plant placed lower, the object positioned in the opposite corner.

Follow the rule of three elements:

▫ Scroll (kakemono) – the vertical element, the “guiding thought.”

▫ Plant (hana) – the living, changeable element.

▫ Object (mono) – the enduring, “silent” element.

Materials and Textures

▫ Wood: In Japan, hinoki (Japanese cypress) or sugi (Japanese cedar/cryptomeria) are traditionally used. In European conditions, good alternatives include pine, oak, or ash. Even untreated plywood can serve—after all, the point is to induce a particular state of mind, not to impress guests.

▫ The back wall can be smooth and matte—clay, paper, or simply painted in a warm, natural tone: beige, grey-green, or muted blue.

▫ The floor may imitate a tatami mat: a thin seagrass rug, a linen runner, a bamboo plank, or a textile mat in a neutral color.

Gloss, plastic, and excess patterns are to be avoided. A tokonoma is a place where materials should look like what they are—without pretending.

Light and Color Palette

Light and Color Palette

A tokonoma does not require separate lighting, but it should ideally be located where the light subtly shifts throughout the day. An alcove that’s too dark loses clarity—too bright, and it becomes just another shelf.

Natural light in the morning or just before sunset is ideal. Avoid direct LED spotlights aimed at the objects—diffused or low lighting is preferable.

The color scheme should be subdued and nature-inspired—the grey of rain, the green of moss, the tone of raw wood, muted whites.

Adapting a Tokonoma in a Polish Home

Even if you don’t have a traditional washitsu, you can create your own tokonoma in one of the following places:

▫ A niche shelf in the living room—remove the books from one level, leaving only a scroll and a tea bowl.

▫ A section of wall in the bedroom—hang a small kakemono, and place an object below on a low pedestal.

▫ A shelf at eye level in the hallway—instead of a key hook, let the sign of the season welcome you.

The most important thing is to designate a space that serves no purpose—other than mindfulness.

Seasonality and the Rhythm of Nature

Seasonality and the Rhythm of Nature

A tokonoma lives in the rhythm of the year. Its contents change with the agricultural calendar and the natural cycle of life. Here are a few examples (highly subjective, completely non-binding—everyone will, in truth, have their own way) of how to compose it throughout the seasons:

▫ Spring: a scroll with a haiku about rebirth, a plum branch (ume), a ceramic jug.

▫ Summer: the calligraphy “ichigo ichie,” a bamboo leaf, a bowl with cool water.

▫ Autumn: a poem by Bashō, a susuki grass stem, a stone reminiscent of a solitary mountain.

▫ Winter: the character jaku (寂 – peace in solitude), a pine branch, a red clay tea bowl.

Changing even one element can completely transform the mood of the alcove.

The Art of Selection: What to Place in the Tokonoma?

Scroll (kakemono)

Scroll (kakemono)

Calligraphy is the soul of the tokonoma. Choose characters with meaning—these can be classic idioms like ichigo ichie (一期一会), single kanji like mu (無 – emptiness), haiku excerpts, sutra fragments, poems by Bashō, Issa, or Santōka.

Plant

The plant doesn’t have to be a full ikebana. A branch, a blade of grass, an unfurled leaf will suffice. Their selection should reflect the moment and place—ideally gathered locally and not evergreen. Observing their change reminds us of impermanence.

Object

Here lies the most room for personal story. It can be anything meaningful to you. In Japan, one often sees: suiseki—a stone resembling a landscape, a ceramic tea bowl, a hand-carved figurine, an old bamboo spoon, a shell. It doesn’t need to be “pretty”—but it must be authentic.

In one tokonoma seen in a rural home on the outskirts of Kurashiki, beneath a scroll with the calligraphy kokyō (故郷 – homeland), stood a single rusted item: gardening shears once used to trim sakura branches. No flowers, no plant—just a tool and a memory.

A reminder that tokonoma does not require decoration—it requires truth.

Just one element is enough, if it holds a memory, a gesture, a story, a season. The rest will be completed by emptiness.

A Manifesto of Silence

The tokonoma reminds us that harmony does not arise from fitting all elements together, but from the brave act of leaving something unfilled. This “frame for nothing”—as Tanizaki wrote—sharpens the contours of the day: it slows the rhythm of thoughts, soothes the eye, and steadies the overstimulated nervous system. In an era that measures time in milliseconds, the tokonoma proposes a thirty-second ritual (a tiny eternity). It’s enough to rest your gaze on the scroll, the shadow under the wooden beam, the slow wilting of a leaf—and allow silence to become a sentence in a dialogue with yourself.

It’s no wonder that designers and minimalist artists return to this alcove as a model: it shows that order is not a matter of symmetry, but of the decision to leave something unfinished. The tokonoma doesn’t ask us to abandon modernity; it merely asks us to frame it—so that noise doesn’t spill beyond the boundaries, and each moment can become ichigo ichie—an unrepeatable encounter.

So if the home today needs a new function, let it be the practice of mindfulness woven into architecture: a small niche in which each day we change a branch, switch a scroll, lift our gaze for a minute. In a world that generates petabytes of action, demanding our attention now, instantly—the tokonoma remains the most modest, and at the same time the most powerful, manifesto: a small pause is all it takes to once again hear all the sounds… of silence.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Turn off the world. Step into the water. Furo

Japanese Karesansui Garden is a Mirror in Which You Can See Yourself

72 Japanese Micro-Seasons, Part 2 – Autumn and Winter in the Calendar of Conscious Living

The Tradition of Kōans in Japan – A Zen Practice That Doesn’t Give Answers, But Takes Them Away

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

The Tokugawa Shogunate: Edo Period (1603–1868)

The Tokugawa Shogunate: Edo Period (1603–1868) What does literature say?

What does literature say? Can You Create a Tokonoma at Home—Here in Poland?

Can You Create a Tokonoma at Home—Here in Poland? Dimensions and Proportions

Dimensions and Proportions Light and Color Palette

Light and Color Palette Seasonality and the Rhythm of Nature

Seasonality and the Rhythm of Nature Scroll (kakemono)

Scroll (kakemono)