The Enduring Legacy of the Bushido Code and Modern Samurai Clans

Bushido: Set of Rules, philosophy, lifestyle

Bushido's seven virtues were not only the framework for the samurai's moral code but also integral components of their training. The first virtue, 'Gi' or rectitude, promoted justice and morality, encouraging samurais to make the right decisions. 'Yuuki,' or courage, went beyond physical bravery, as it also demanded spiritual and moral strength. 'Jin,' or benevolence, taught them compassion and sympathy towards others. 'Rei,' or respect, guided their interaction with others, promoting politeness and honour. 'Makoto,' or sincerity, emphasized the importance of truthfulness, while 'Meiyo,' or honour, demanded they live and die with dignity. Finally, 'Chuugi,' or loyalty, was about unwavering devotion to their master and cause.

Even though the samurai era officially ended in the mid-19th century with the Meiji Restoration, the spirit of Bushido continues to influence contemporary Japanese society. The principles that once guided the samurai are now entrenched in the societal norms of Japan. The virtues of honour, respect, and loyalty are echoed in interpersonal and professional relationships. Moreover, martial arts, which evolved from samurai combat techniques, still teach principles of Bushido to practitioners. Kendo, Judo, and Aikido, for instance, emphasize respect for the opponent, mastery of the self, and the promotion of peace, values inherent in Bushido.

Bushido was a lifestyle as well as a philosophy, a blend of Zen Buddhist doctrines, Shinto spirituality, and Confucianism, manifesting in seven key principles: rectitude (Gi), bravery (Yuuki), love (Jin), politeness (Rei), truthfulness (Makoto), honor (Meiyo), and loyalty (Chuugi). These principles encapsulate the virtues a samurai was expected to embody. The nobility and courage inherent in these principles were not just physical but also intellectual and moral.

In the post-Bushido era, samurai clans continued to hold significant influence, morphing into roles within politics, academia, and business, as their martial might became less relevant in a modernizing Japan. Some clans maintained their prominence despite the downfall of the Samurai class during the Meiji Restoration in 1868. Even though the Samurai class was formally abolished, the influence of the samurai ethos persisted, leading to the emergence of modern-day Samurai clans, who, while not wielding swords, continue to honor the legacy of their ancestors.

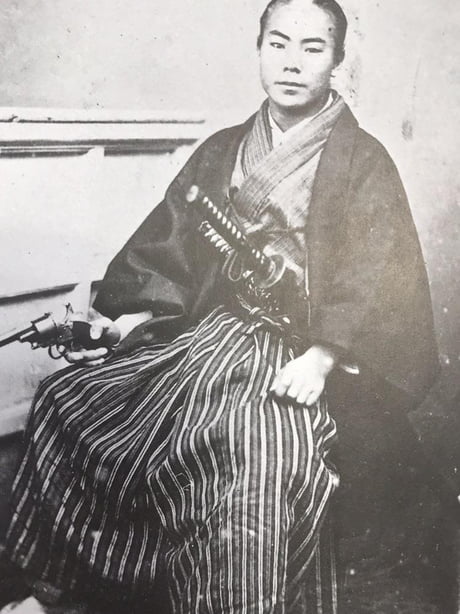

Samurai: from bloody clan wars to peaceful social leaders

During the Edo period, Japan experienced an era of unprecedented peace, characterized by economic growth, strict social order, isolationist foreign policies, and an appreciation of the arts. This peaceful period saw the samurai class' transformation from warriors engaging in a bloody cycle of clan warfare to a more refined class of societal leaders. No longer needing to rely on martial prowess to ensure their survival or status, the samurai began transitioning into roles of leadership and administration, their martial skills becoming more symbolic than practical.

The samurai became bureaucrats, scholars, and educators during the Tokugawa Shogunate. This metamorphosis in their status reflected the broader societal shift towards valuing intellectual pursuits alongside martial valor. The samurai's strict adherence to the Bushido code—emphasizing honor, bravery, loyalty, and self-discipline—also made them ideal role models for the broader Japanese population. Their transformation represented an evolution in Japan's cultural and societal norms, with the warrior class's principles becoming an integral part of the national ethos.

However, not all samurai could smoothly adapt to the changing social landscape. This shift led to the emergence of the 'ronin,' a class of masterless samurai. The term 'ronin' translates to 'wave man,' connoting a sense of drifting without purpose or direction. These were samurai who had lost their masters through death or disgrace and were not reabsorbed into the rigid samurai hierarchy. They had to eke out a living on their own, sometimes turning into mercenaries or resorting to banditry.

The ronin were considered a social problem during the Edo period, as they posed a potential threat to the established order. The ronin had the skills and training of the samurai but lacked the restraining influence of a master. These masterless samurai were often seen as ticking time bombs that could instigate unrest or rebellion. The famous 47 Ronin's tale epitomizes the paradox of the ronin — they were symbols of both the best and worst of the samurai class. Their tale of loyalty and vengeance has been celebrated in Japanese culture, while their existence as masterless, wandering warriors remains a symbol of the disruptive forces that eventually led to the downfall of the samurai class.

The fall of Samurai

As the samurai era approached its twilight years, the winds of change were blowing over

In the years preceding the Meiji Restoration, a noticeable shift was occurring within the samurai ranks. Recognizing the changing global dynamics, many samurai began advocating for military reforms. They acknowledged the widening gap between Japan and Western countries in terms of military technology and organization. There was a widespread realization that Japan needed to evolve to maintain its sovereignty and secure its future. It was during this period that the samurai, known for their martial prowess, began to morph into diplomats and reformists, advocating a broader perspective of power and authority that went beyond the traditional warrior codes.

The Meiji Restoration, which began in 1868, catalyzed a profound transformation in Japan. The imperial rule was reinstated, marking the end of the shogunate system. With the fall of the shogunate came the abolition of the samurai class. The samurai, who had enjoyed a privileged position in society, found themselves bereft of their hereditary rights and responsibilities. They were stripped of their lands, stipends, and even their symbolic samurai swords, the carrying of which became illegal in 1876.

This decree was a massive cultural shock, marking the definitive end of an era. The samurai were thrust into an unfamiliar social landscape where they had to adapt or perish. Many began to transition into different industries, taking on roles as educators, businesspeople, or entering other professional occupations. The once privileged samurai class essentially dissolved into the broader populace, becoming an integral part of the new, modernized Japan.

Yet, despite this dissolution, the cultural identity of the samurai persisted. The samurai's descendants carried forward their ancestors' legacy, imbibing their values and traditions. They became representatives of a bygone era, custodians of a rich and complex cultural history.

Today, these descendants continue to contribute to Japanese society, serving as an enduring reminder of the samurai spirit. Whether through their work, their lifestyle, or their dedication to traditional Japanese arts and disciplines, they keep the memory of the samurai alive. The story of the samurai, from their rise to their demise, stands as a poignant testament to the resilience and adaptability of Japan and its people in the face of change.

Modern Samurai today

While the samurai era ended with the Meiji Restoration, its cultural and societal impacts continue to resonate in contemporary Japan, and nowhere is this more apparent than within the families that can trace their lineage back to these noble warriors. One such family, the Tokugawa clan, boasts an impressive historical legacy. Once the ruling shogunate, the Tokugawa clan was pivotal in shaping the history and culture of Japan.

One member of the Tokugawa clan who personifies this transition is Tsunari Tokugawa. A direct descendant of the last shogun, Tsunari represents a fusion of the old and new, a bridging link between Japan's feudal past and its contemporary reality. As a notable figure within the Nippon Yūsen shipping company, he made his mark in the world of business. However, he did not sever ties with his samurai heritage.

In his retirement, Tsunari leads the Tokugawa Foundation, which is dedicated to preserving the cultural treasures of the Tokugawa samurai family. Through this endeavor, he keeps the samurai spirit alive, ensuring the lessons and values passed down through generations do not fade into oblivion. In a world driven by technology and globalization, Tsunari and his foundation stand as reminders of the rich cultural heritage of Japan.

Legacy and the world after

Beyond the legacy of individual clans like the Tokugawa, the influence of the samurai era is evident in the very fabric of Japanese society through the principles of Bushido. The samurai code, centered on seven key virtues, continues to be an essential part of Japanese cultural values. Respect and courtesy, or Rei, are integral to Japanese etiquette and interpersonal interactions, mirroring the deep-seated samurai ethos.

In business, the principle of Makoto, or truthfulness, forms the cornerstone of ethics. It reinforces trust and honesty in commercial interactions, shaping the conduct of corporations and business people. The concept of Meiyo, or honor, remains deeply entrenched in society, influencing the emphasis on maintaining face and societal reputation. Finally, the principle of Chuugi, encapsulating loyalty and devotion, reflects in the Japanese tradition of lifelong employment.

In conclusion, the spirit of the samurai, embodied in the Bushido code, has left an indelible mark on Japanese society, surviving the abolition of the samurai class and the modernization of Japan. Even though we no longer see samurai wielding their katanas, the principles they lived by permeate the fabric of Japanese society. The modern-day samurai clans continue to honor their lineage and uphold their cultural heritage. They serve as living testimonies to a bygone era, safeguarding their ancestors' values and traditions. The enduring legacy of the Bushido code, together with the samurai clans, serve as the custodians of an age-old culture, ensuring that the 'way of the warrior' continues to guide and inspire future generations.

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!