Ikkyū Sōjun: The Zen Master Who Found Enlightenment in Pleasure Houses with a Bottle of Sake in Hand

Singing Zen

Singing Zen

In 15th-century Japan, there lived Ikkyū Sōjun, a Zen master unlike any we might imagine—a wanderer with a black bowl in hand, a lover of wine, women, and life in its wildest form. This spiritual rebel, who sang songs in pleasure houses instead of chanting sutras, and who chose evenings with a bottle in the company of dockside vagrants or prostitutes over Zen ceremonies, shook the very foundations of Buddhism in his time. His poetry challenges the rigidity of temples:

"The monks in this temple—

their meditation is an empty spectacle.

Beyond their walls, under the stars,

the old donkey finds Zen truth."

"The truth lies in silence—(…)

I am silent when I am drunk,

and when I sing, Zen can be heard."

His life was like a Buddhist koan: a Zen master who criticized the institutions of Buddhism as corrupt and vain, yet remained steadfastly loyal to the spirit of the tradition. For Ikkyū, Zen was a living experience—savoring wine, singing songs, loving women, and finding truth in every breath. This untamed energy of life made him a figure both fascinating and challenging to understand.

The story of Ikkyū Sōjun is not merely one of a spiritual rebel—it is an invitation to reflect on what it means to live in harmony with one’s true nature. As he said, Zen is everywhere—if only one has the courage to see it.

The Life of Ikkyū Sōjun

Childhood and Heritage

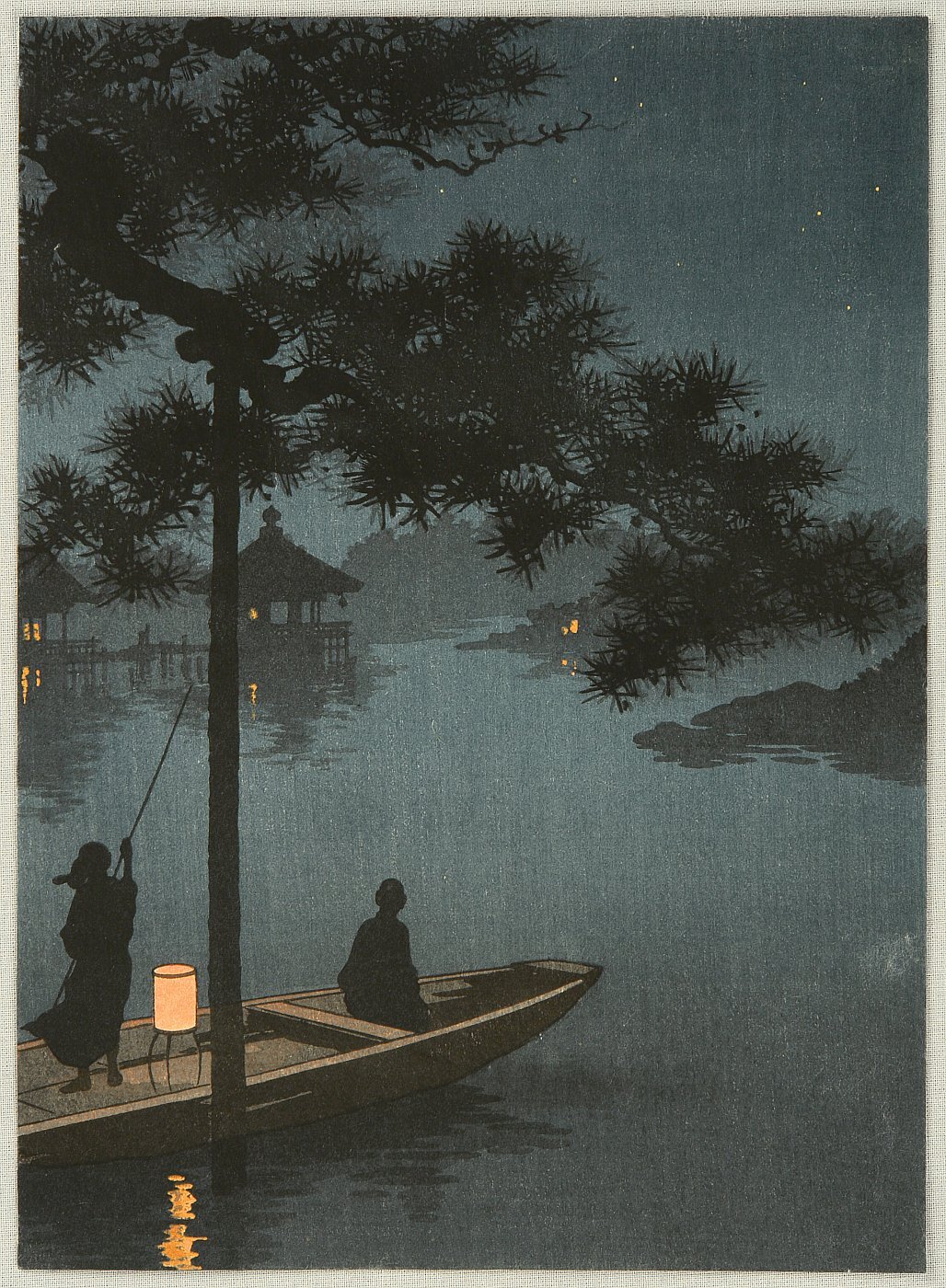

Fifteenth-century Japan was a land in constant flux—teeming with life but torn apart by conflicts. On the narrow streets of Kyoto, the then-capital, crowds bustled daily among wooden buildings where stalls offered finely crafted textiles, incense, and ceramic tea bowls. The air smelled of damp earth, rice, and chimney smoke, and temples dominated the skyline—spiritual centers where sutras were whispered to the rhythm of the wooden mokugyo. Yet beneath this peaceful surface, wars raged—feudal lords vied for power, and Kyoto, the city of emperors, was increasingly overshadowed by the rising samurai class.

In this turbulent era, in 1394, a boy was born whose life would unfold as an extraordinary tale. Rumored to be the illegitimate son of Emperor Go-Komatsu and a low-ranking court lady, his mother, banished from the palace, fled to the outskirts of Kyoto, where she raised him in secrecy. Could this boy, named Sengikumaru (千菊丸), comprehend the weight of such a legacy? In his mother’s eyes, he must have been both a miracle and a curse—a reminder of love and betrayal that cost her her place at the imperial court.

Early Years at Ankokuji Temple

Sengikumaru—now known as Shūken (宗堅, literally “steadfast in study,” a typical name for young acolytes)—quickly distinguished himself with his intelligence and talent for poetry. Yet his heart was often gripped by loneliness and a sense of emptiness. In the silence of the temple garden, the boy likely asked himself: “Why was I left here? Is this place meant to make me extraordinary or strip away everything human?” Perhaps he also wondered, “Where is my mother now?”

A Young Monk’s Conflicts

A Young Monk’s Conflicts

As a teenager, Shūken increasingly sensed the hypocrisy surrounding him. Monks, who were supposed to be spiritual guides, often boasted about their lineage, shattering his image of pure Zen described in the sutras. “Is this the path to enlightenment for which I endure this confinement?” he likely thought bitterly.

At the age of thirteen, he was transferred to Kennin-ji, a larger and more prestigious temple. But life there disillusioned him even further. Instead of genuine zazen practice, he saw only competition for status and boastful displays of literary prowess. In his early poems—brief yet brimming with rebellion—he described this emptiness and hypocrisy. In one, he wrote:

"Studying the Way and practicing Zen

causes the loss of the original mind.

The song of a fisherman is worth a thousand pieces of gold.

The evening rain on the Xiang River,

the moon amid the clouds of Chu—

unceasing furyū,

night after night, reciting poems."

The Path to Enlightenment

The Path to Enlightenment

Ikkyū Sōjun, then still the young Shūken, embarked on his spiritual journey with an insatiable hunger for authentic Zen—not the rigid, hierarchical Zen of empty rituals, but one vibrant with life. The first master to profoundly influence him was Ken’o, a stern teacher from a small temple on the shores of Lake Biwa. Ken’o did not believe in flowery phrases or displays of erudition; for him, true Zen resided in simplicity and zazen, meditation grounded in breath and complete immersion in the present moment.

Ken’o could remain silent for days, and his teachings were as profound as the deep waters of Lake Biwa itself. Often, when the young Shūken grappled with a koan, Ken’o would offer remarks like, “Silence your mind, or you’ll be like a tree pruning its own branches!” He was the first master to show Shūken that Zen was not about words or form but about the direct experience of reality. When Ken’o passed away in 1414, Ikkyū was overcome with despair, feeling as though he had lost his guide.

A New Master and a Turning Point

A New Master and a Turning Point

After Ken’o’s death, and following a period of despair that nearly led him to suicide, Shūken found another teacher—Master Kasō, who presided over Zenko-an, a small temple associated with the prestigious Daitokuji. Kasō was equally austere but more methodical. Working through koans under his guidance was like navigating a labyrinth—filled with frustration but leading to moments of clarity. In 1420, after years of practice, Shūken experienced satori, his first deep awakening.

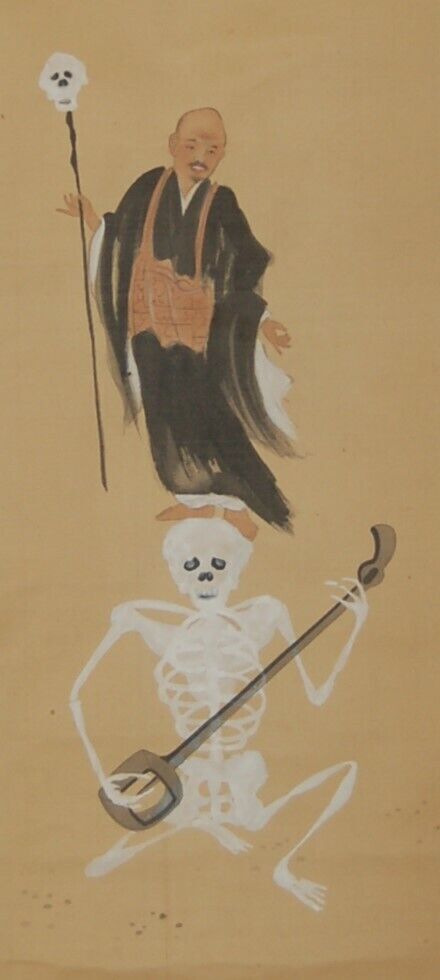

Ultimately, Ikkyū burned the inka, emphasizing his rejection of formalities and religious hierarchy. For him, Zen was not something that could be conveyed through paper, titles, or ceremonies. It was a living experience, one that could be found anywhere—in the cry of a crow, the taste of sake, a lover’s smile, or even in chaos and suffering. By rejecting the inka, Ikkyū symbolically declared war on the corrupt Zen of his time, whose temples were more concerned with wealth and prestige than with spiritual practice.

In doing so, Ikkyū became a rebel—a "crazy cloud" wandering Japan, ever faithful to the simplicity and authenticity of Zen. His life was to serve as proof that spiritual awakening requires neither titles nor temples but only the courage to look inward and see the world as it truly is.

Years of Wandering and Rebellion

Years of Wandering and Rebellion

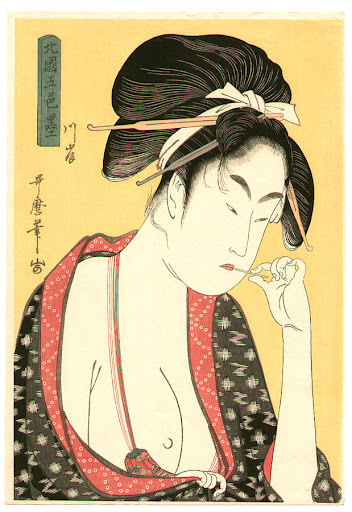

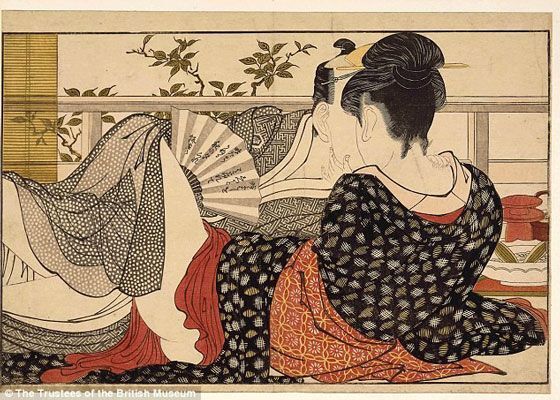

Now a mature monk and poet, Ikkyū veered off the beaten path followed by others. Instead of retreating within temple walls, he set out into the world as a wanderer—a rogue pilgrim seeking truth where others saw only disgrace. His bare feet traversed the cobbled streets of Kyoto, rice fields in the provinces, and the quiet alleys of port towns, where the air was thick with the scent of sake and sweat. Wine, prostitutes, and poetry—these were his tools for Zen.

In one of his poems, the simplicity of life and his disdain for conventions are palpable:

"The monks in this temple—

their meditation is an empty spectacle.

Beyond their walls, under the stars,

the old donkey finds Zen truth."

In his poetry, prostitutes and physical love took on an almost sacred significance:

"Eight sun strong—

my favorite thing.

When I am alone at night,

I hold it tightly—

a beautiful woman hasn’t touched it in ages.

The whole universe is in my fundoshi!"

Yet as he wandered, he also saw how Zen, which was meant to be a path of simplicity and truth, had become a machine driven by ambition. Grand temples amassed wealth, monks competed for influence, and the spirit of Zen was diluted by vain ceremonies. Ikkyū spared no words in criticizing those who, in his view, had betrayed the true essence of the practice.

In one of his most cutting poems, he wrote:

"What are these temples,

these grand halls full of gold?

Monks like peacocks,

filled with pride.

Under an old tree,

a fisherman sings true sutras."

Though a vagabond, Ikkyū remained a spiritual teacher, and his poems were his teachings. One of his reflections sums up his years of wandering and rebellion against conformity:

"Do not trust the words written by great monks.

Truth lies in silence—

but they are afraid to be silent.

I am silent when I am drunk,

and when I sing, Zen can be heard."

For Ikkyū, his travels, critique of corrupt Zen, and raw engagement with life in its most intense forms were his path to Enlightenment. Wine and women, meditation and reflection—these were his passions. As he wandered, he proved that Zen could be found anywhere—in the depths of a forest, in the laughter of a prostitute, or even in the noise of a marketplace. His rebellion and poems became the voice of Zen beyond temple walls—authentic, unbound, and alive.

Ikkyū was also a harsh critic of the corrupted Zen of his time. His poems are filled with sharp words aimed at monks who, in his eyes, betrayed the spirit of the tradition by turning it into a tool for accumulating wealth and power. "Monks in golden halls, like peacocks full of pride," he wrote, contrasting the opulence of temples with the simplicity of a fisherman's or prostitute's life. To him, true Zen was not found in ceremonies or riches but in everyday experiences that reveal our true nature.

Ikkyū's work defies easy classification. It is a blend of sensuality and spirituality, irony and depth. It compels us to reflect on what it means to be human—to embrace our desires, fears, and limitations while still striving for something greater.

Ikkyū as a Koan

Ikkyū teaches us that spirituality is not about escaping life but about fully participating in it. Wine, laughter, sensual pleasures, as well as pain and solitude—all are parts of the path that cannot be rejected if one seeks true understanding. His message is not an easy one. It requires courage to look at oneself without judgment and to accept both one's light and shadow. It demands a willingness to abandon what is familiar and comfortable and venture into the unknown—where there are no certainties or clear answers.

Ikkyū's work is a kind of nudge: "Do you really understand what it means to be human?" His courage to challenge both himself and the world around him reminds us that spirituality is not a distant ideal but a daily effort to be authentic.

"If the rain is to fall, let it fall.

If the wine flows, let it flow.

Under a bridge or in a palace,

Zen is everywhere,

if you have the courage to see it."

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

How to Stop Fighting Yourself at Every Turn? Wabi Sabi Is Not Interior Design but a Way of Life

Maurycy Beniowski: The Adventures of a Daring Pole in Edo Period Japan

Japanese Karesansui Garden is a Mirror in Which You Can See Yourself

Spiritual Landscapes in Japanese Sumi-e Art

Japanese Gardens: A Piece of Art with a Surprising Ending - Discover the Secrets of Zen Gardens

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Singing Zen

Singing Zen

A Young Monk’s Conflicts

A Young Monk’s Conflicts The Path to Enlightenment

The Path to Enlightenment A New Master and a Turning Point

A New Master and a Turning Point Years of Wandering and Rebellion

Years of Wandering and Rebellion