Smoke and Jazz of the Shōwa Era – What Do Coffee and Nostalgia Taste Like in Japan’s Kissaten?

“Hospitality – Priceless”

This place is called kissaten – 喫茶店 – literally: “a place for drinking tea.” But the name is misleading. Since the early 20th century, kissaten have become Japan’s coffee sanctuaries – spaces of silence, contemplation, and ritual. These are not venues for a quick caffeine fix or social chatter. They are places where the brew is savored slowly, the music chosen from a personal vinyl collection, and the owner remembers exactly which cup you like best. At their peak, Japan had over 150,000 such establishments. Today, their numbers have dramatically declined – but there are still those who seek in them something no chain café can offer: authenticity, atmosphere, and soul.

In today’s article, we’ll step inside the kissaten. We’ll trace their history – from Dutch coffee in the port of Dejima to the vinyl jazz era in Shinjuku’s smoky basements. We’ll explain what 喫茶 means, how a jun-kissa differs from a jazz-kissa, who the owners known as masters are, and why coffee here doesn’t taste the same as anywhere else. There will also be smoke, rhythm, porcelain – and time, which flows differently when a cup cools slowly. So come along – into a world that exists beyond current trends.

What Is a Kissaten?

「コーヒー 450円 おもてなし プライスレス」

“Coffee – 450 yen. Hospitality – Priceless.”

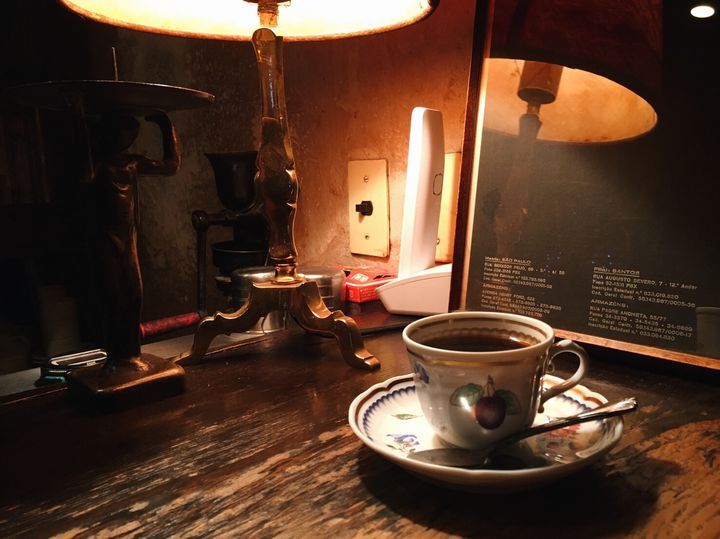

When you push the door, a bell rings. Inside, a warmth welcomes you – not from a heater, but from the wood, the scent of coffee, and the human presence that surprises at first, because it’s so quiet. The walls are lined with dark wood, occasionally adorned with yellowed photographs and posters from jazz concerts of the 1970s. Behind the counter – a polished lever espresso machine, porcelain cups arranged in perfect rows, a radio playing softly as if from another world. The patrons – an older man reading a newspaper and slowly stirring sugar in his glass; a pair of students hunched over a photo album; a woman in a dark kimono, pensive, her fingers resting on the edge of a cup, as if trying to recall a long-forgotten name.

Everything here seems to persist – not to happen. It is not a place for doing, but for being. In such a kissaten, time flows differently, and the space itself acts as a quiet catalyst – inviting focus and silence, sometimes important conversations, sometimes entirely trivial ones, or reflection, which so often slips away amid the daily noise. A single cup is enough to spend an hour, two, half a day. You need not prove anything here, do anything, or be anyone special.

That is what a kissaten is – a Japanese café not merely for coffee. It exists for presence.

The word kissaten (喫茶店) consists of three kanji characters:

→ 喫 (kitsu) – means “to consume” or “to drink” (with a subtle nuance of ceremony or pleasure)

→ 茶 (cha) – “tea” (which may seem counterintuitive since we’re talking about a coffee shop)

→ 店 (ten) – “shop” or “place, establishment”

Over time, many terms emerged to describe the different varieties and incarnations of this phenomenon:

- kissaten – a classic, often old-fashioned Japanese-style café;

- kafe (カフェ) – borrowed from French, now typically refers to modern, “Western” cafés (often chain stores);

- jazz-kissa (ジャズ喫茶) – special kissaten where jazz plays from vinyl, often on powerful audio equipment;

- milk hall – a historical term, popular during the Meiji and Taishō periods, referring to cafés that served milk and light Western-style snacks;

- sabo (茶房) and saryō (茶寮) – more artistic, stylized cafés, often linked to tea traditions and the aesthetics of wagashi (Japanese confections).

Each of these places differs in detail, but one thing unites them: coffee is not a product here – it is an experience. And the place itself – not a service point, but a space for encounter. With oneself, with others, with nostalgia.

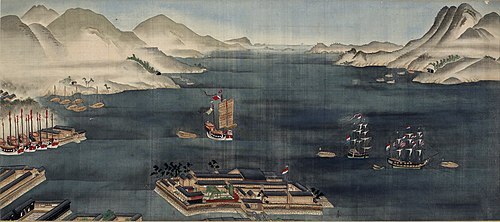

From Dejima to Shōwa – The History of Coffee and Kissaten in Japan

It wasn’t until the second half of the 19th century, after the fall of the shogunate and Japan’s opening to the world, that coffee began to take root on Japanese soil. In 1888, Tei Ei-kei (鄭永慶), a wealthy entrepreneur educated at Yale, opened in Tokyo the first fully functioning establishment serving coffee: Kahiichakan (可否茶館). This place was not merely a café – it was a vision of London’s “penny universities,” where for the price of one cup of coffee, one could sit at a table with thought, debate, and discussion. Guests read newspapers, exchanged opinions, listened to lectures. Coffee was the pretext, culture – the purpose.

During the Meiji and Taishō eras (late 19th and early 20th centuries), cafés – increasingly called kissaten – flourished as modern meeting spaces that blurred old social divisions. Women, still officially excluded from many areas of public life, began to visit cafés. So did moga (modern girls) and mobo (modern boys) – young people enamored with Western lifestyles, but also seeking their own identity amid the urban bustle. The café became a mirror of the era – a place of flirtation, solitude, reading, and transformation.

It was during this period that two essential pillars of kissaten philosophy took shape:

- Kodawari (こだわり) – an obsessive attention to detail: every stage of brewing, the exact weight of the grounds, the water, the timing.

- Wakon Yōsai (和魂洋才) – “Japanese spirit, Western technique” – the belief that foreign elements can be adopted without losing one’s own identity. The coffee was Western, but the atmosphere, rhythm, and etiquette remained deeply Japanese.

After World War II, in a devastated country, kissaten became sanctuaries for the soul. Cities were rebuilding from the rubble, society was beginning a new chapter, but cafés remained – warm, fragrant, familiar. Amid rapid urbanization and the brutal acceleration of daily life, kissaten offered silence, repetition, and a small daily ceremony. They became part of the mental landscape of postwar Japan.

Interiors and Atmosphere: Light, Smoke, and Jazz

The décor is old-fashioned, but not retro. It’s not stylization – it’s memory. You’ll often find a calendar from the 1980s, a pendulum clock, a rack of yellowing Shūkan Bunshun magazines, a carved bar, and vinyl records in the corners. In some places, nothing has changed in half a century. Guests sit at the same tables, order the same coffee, and sink into their thoughts. Kissaten are rooms suspended in time – separate worlds that refused to go with the flow.

You won’t find trendy neon signs, latte art hearts, or baristas in logo aprons. Instead: a mustachioed man behind the counter, who’s known his customers by name for decades and remembers who takes how much milk in their coffee, at what temperature. Instead of a quick espresso to go – a slow-brewed pour-over, with water gently guided through a porcelain filter by hand.

What unites all these places is a shared aura of contemplation. Regardless of the noise outside, the interior of a kissaten acts as a soundproof barrier for the soul. People come not just for coffee, but for a state of mind – for a moment to be alone with one’s thoughts, a newspaper, a cup. As if the world paused for a moment in the sound of old vinyls and the scent of coffee that tastes like nowhere else.

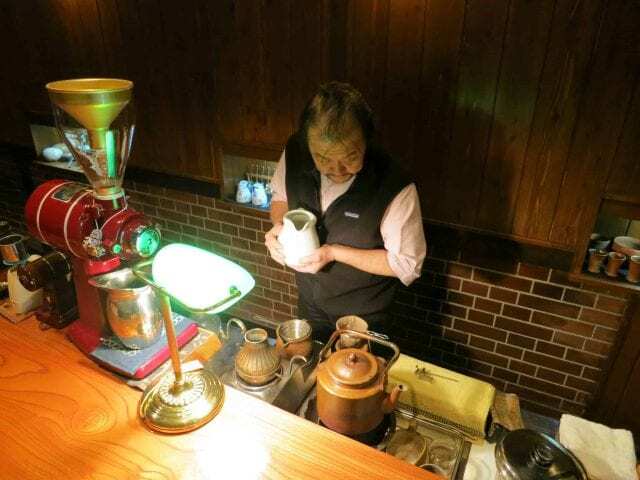

Masters and Mamas – The Souls of the Kissaten

In the Master’s café – everything is different. No one talks – only contemplates. Silence has its own temperature, and voices sink into the cigarette smoke and the notes of jazz trickling from vinyl. The Master asks no questions. He brews coffee in silence, with such focus that no one dares to interrupt. Even his regulars share not friendship, but a discreet communion of ritual – the same men, the same seats at the counter, the same order of drinks. When one leaves, the other instinctively takes his place – a choreography like in nō theatre, where every role and movement holds meaning.

What unites these two venues – though they differ like fire and water – is kodawari (こだわり): a term difficult to translate, signifying a pursuit of perfection in detail, a passion for quality, a stubborn devotion to craftsmanship. For a kissaten owner, kodawari may mean:

- choosing a specific filter for a specific type of bean

- remembering that Mr. Sato likes his coffee with one spoon of sugar – but only on Mondays

- selecting a cup from the collection not by whim, but according to the guest’s character and the type of brew

- wiping the counter with motions repeated for thirty years – in exactly the same order.

Perhaps that is precisely why true kissaten have survived the era of trendy chains. Because they cannot be duplicated – for that, one would have to replicate not only the interior, but the human being as well. And a person with passion, memory, and principles – that is something which, in today’s world, tastes just as rare as siphon-brewed coffee in a porcelain pot.

Ritual and Technique: Coffee as Ceremony

Ritual and Technique: Coffee as Ceremony

In a kissaten, coffee is not a beverage – it is a ritual. One does not drink it in a rush, nor grab it in a cardboard cup with a plastic lid. Here, coffee is a process – slow, quiet, meditative. One glance at the owner’s hands is enough: for over two minutes, he slowly, in a circular motion, guides a stream of hot water over the cone-shaped filter. This is not merely brewing – it is a personal chanoyū ceremony, only with coffee instead of tea, and a steel kettle in place of a chawan teapot.

All this serves the dark roast – dense, strong, full of chocolate and nutty notes. No sour, light roasts here. In kissaten, coffee is meant to have the depth of melancholy, the bitterness of afternoon, the warmth of memory. Many establishments rely on blends based on Brazilian beans – and not without reason. This is the legacy of Café Paulista, one of Japan’s first coffeehouses, founded in 1911 in Ginza, which imported beans from plantations run by Japanese immigrants in Brazil. It was there, on the far side of the Pacific, that Japan’s taste for coffee was shaped – bean by bean, generation by generation.

You won’t find the slogan “coffee to go” in a kissaten. There is no “to go” here – coffee is not meant for escape, but for stillness. Before you even sit down, the waiter (or the owner himself) will hand you a small moistened towel – chilled with ice in the summer, warm as a coat pocket in the winter. This is oshibori – a ritual of cleansing, both physical and symbolic. A moment later, a glass of cold water appears – not to quench thirst, but to prepare the palate. Only then, when you are calmly seated, does it become time to order.

The entire experience is infused with omotenashi – but not the pushy, corporate kind. It is the subtle, anticipatory Japanese hospitality (see omoiyari: Omoiyari and the Culture of Intuition – The Deepest Difference Between the European and Japanese Mindsets?). A mindful concern that you feel not just served, but welcomed. That is why in many kissaten, the bill is not brought to the table. There is no shouting of “next!” or the noise of a pressure espresso machine.

Nostalgia and Continuity

In the 1980s and ’90s, as Japan raced toward its economic zenith and cities were draped in glass and neon, kissaten began to disappear from the map of daily life. Their place was taken by chain cafés – first Doutor, then Starbucks, and the whole coffee globalization with its plastic lids. Young people stopped visiting cafés without Wi-Fi or soy lattes. Many old kissaten closed for good – without successors, without heirs.

And yet – something endured. Kissaten did not vanish. They simply went deeper. Into side streets, into basements, into the memory of generations. And when the world came full circle, a new generation began rediscovering the charm of these places. Instagram began to fill with photos of old coffee cups, worn menus, 1970s ashtrays, white aprons, and the rough hands of masters. Retro returned – not as decoration, but as a yearning for slowness, depth, and authenticity.

In Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka, new kissaten are opening today – inspired by the spirit of Shōwa, but with a fresh sense of form. Fanzines and photo books documenting these places are being created. Manual brewing techniques are returning, new artisanal blends are emerging. Some kissaten from the 1960s are now run by the grandchildren of the founders, preserving the original décor.

Kissaten are becoming an archipelago of memory – islands of resistance to haste and uniformity. They are like old mechanical watches – bulky, outdated, but alive, ticking to a rhythm no one learns to hear anymore.

This is precisely why these places defy simple categorization. They are neither museums of the past nor merely coffeehouses. They are microcosms of memory. Sitting in such a place, you cannot quite tell whether you are in 1975, 1998, or yesterday. Because kissaten is not an era – it is a state of mind.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

The World of Japanese Karaoke Bars – From Intimate Boxes to Business Teleconferences

Turn off the world. Step into the water. Furo

Haikyō Onsen – Japanese “urbex” amid the abandoned beauty of 1980s resorts

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Ritual and Technique: Coffee as Ceremony

Ritual and Technique: Coffee as Ceremony