I don’t know who I am or why I’m here – so I put on a samurai armor and start scrolling. Ironic Compassion in the Art of Tetsuya Noguchi

What to do with oneself after stepping off the stage?

Tetsuya Noguchi’s work is not, however, an homage to history – it depicts us, not samurai. Sometimes, when we are defenseless, we move through the world in mighty armor atop a pathetically inadequate bicycle, heading nowhere with no purpose at all. Noguchi asks what remains of our former ideals. Are we still ready to fight — even though we no longer know with whom, for what, or why? We are like actors who, after the performance is over, do not take off their costumes because they don’t know what to do with themselves after stepping offstage – where to go, what to do next. Warriors who dream not of epic victories but of peace and quiet. Through the samurai masks in Tetsuya’s art, a deeper question shines through – who are we – and are we still anyone at all? Let us try to seek an answer today in selected works by this singular Japanese artist.

“Armored Warrior Going into Battle on a Bicycle”

- Tetsuya Noguchi, 2013, 「野口哲哉の武者分類図鑑」

(“An Illustrated Catalog of Warrior Classification by Tetsuya Noguchi”)

At first glance, it looks like an illustration from a textbook on feudal Japanese history: a samurai in full gear, bent in a battle-ready pose, prepared to strike. But from the very first look, we sense that something is off, and the longer we gaze, the more things begin to feel out of place. In this extraordinarily evocative work by Tetsuya Noguchi, what draws the eye is not just the composition and detail, but above all the contrast between the monumental weight of the armor and the absurdity of the mode of transport: this samurai is heading into battle on a bicycle.

It is a painting on paper with Noguchi’s characteristically subtle palette of earthy, subdued tones. The texture of the background and the washi paper, visible in the light, gives it a tangible depth. The lines are precise, as if drawn from the tradition of Japanese painting and woodblock printing, and the composition – classical. We have it all here: a meticulously rendered armor, the clan crest on the helmet, the lacing, the sode, the kabuto helmet. From a distance and from above – the work could pass for a realistic portrait of a 16th-century warrior. Up close – it is clearly a joke. But not entirely.

For although the juxtaposition of samurai and bicycle seems on the verge of comedy – heightened by the contrast between the battle gear and the figure’s thin, weak arms and calves – the whole image carries a melancholic undertone. This warrior does not laugh. He is serious. He moves forward with tension in his body and contemplation in his eyes. And it is precisely this seriousness in the face of an absurd situation that makes the image so compelling. It’s not a parody, but something much deeper: a portrait of the modern human.

Noguchi’s samurai becomes here a symbol of each of us who, every day, puts on an “armor” – a social role, a posture, a duty – and heads out on equipment utterly unsuited for the role. A bicycle instead of a horse. Tension in the body and aimlessness in the background. It is an image of the inner dissonance between who we want to be and what we actually have to work with. We want to be great warriors fighting for noble, lofty goals, but we are defenseless, moving forward on a pitifully inadequate bicycle, heading nowhere with no purpose at all.

Noguchi, however, does not mock. He sympathizes. He shows a noble yet lost human being. Clad in ancient authority, yet confronted with a completely new, absurd reality. In a world without battles and without enemies within sword’s reach, the warrior remains a warrior merely out of habit. He goes “into battle,” though the war ended long ago. Or perhaps never even began.

It is worth noting that this same motif also exists in sculptural form – equally detailed, crafted from resin and synthetic fibers – exhibited, among other places, at Tokyo’s Nerima Art Museum (a typical practice for Noguchi: he often creates the same figure both as a painting and a sculpture). Regardless of medium, the message remains the same: the grotesquery of daily life, armor as a metaphor for psychological weight, and a whole composition that balances between humor and existential sadness.

Noguchi asks what remains of our former ideals. Are we still ready to fight – only we no longer know with whom, for what, and why? Or are we simply moving forward, on whatever we can, just so we don’t have to stop? We crank the mechanism, pedal stubbornly, so the little bike keeps rolling forward, just so we don’t stop. In this single image – so quiet and so full – lies the story of many of us.

Who is Tetsuya Noguchi?

He graduated from Hiroshima City University, first in oil painting (2003), and later with a master’s degree (2005), where he honed his craft but also began to develop his own visual language. From the start, he was drawn to precision, detail, the world of the possible and impossible. As a child, he assembled models of robots and science-fiction vehicles, was fascinated by samurai, Japanese history, and... plastic. This blend of past and plastic turned out to be key to his mature art.

The second figure who had a strong influence on his work was Kobori Tomoto (1864–1931) – an artist and scholar known for his obsessive reconstructions of samurai armor and courtly costumes. Kobori did not merely paint warriors – he sewed and wore reconstructed garments himself, photographed himself in them, and studied every detail of ancient techniques. For Noguchi, he was not only a visual inspiration, but also a philosophical one – as an artist who does not merely recreate history but lives it.

Noguchi’s art balances between classical and contemporary not only in theme but also in technique. In his paintings, he often uses acrylic, but paints on washi paper or wooden panels in a style reminiscent of nihonga and ukiyo-e. Sometimes his works take the form of drawings that resemble medieval illustrations from a lost manuscript. In sculpture, he employs epoxy resin, synthetic fibers, and occasionally elements of fabric, leather, or even artificial fur. All this serves to create an illusion: a work that looks like an antique, though it was made with 21st-century methods.

But equally important – Noguchi does not mock. He does not deconstruct history in a spirit of cynical irony. His attitude toward samurai – and toward the human condition in general – is filled with quiet compassion. Yes, his warriors may be ridiculous: they wear headphones, carry bags with the Chanel logo, sit on bicycles or stare at phone screens. But they are not caricatures. They are rather tragicomic figures – like actors who have forgotten that the play is over, and do not remove their costumes because they don’t know what to do with themselves after leaving the stage.

Noguchi is also a literary artist. He adds “catalog” descriptions to many of his works – stylized as pseudo-scientific, museum commentaries. He writes about the supposed origin of a crest, analyzes the sculpture of a bicycle in the context of the warrior’s social status, mentions fictional eras and masters. He does so with a straight face and a language so artfully disguised as academic jargon that it is hard to detect the joke right away. Yet the purpose of these texts is not comedy. They are meant to make us ask: what do we believe when we look at “historical truth”?

What is the art of Tetsuya Noguchi?

Noguchi does not create nostalgic visions. His art is neither a return to tradition nor a mockery of it. Rather, it is an analysis of cultural illusions – executed with surgical precision, yet with human compassion. Noguchi’s style is a combination of painterly realism and conceptual gesture: every detail serves the idea, but the idea itself is never imposed. The artist leaves room for silence, hesitation, helplessness. Because the hero of his works – the supposed samurai – doesn’t know who he is.

It is no coincidence that one of his exhibitions was titled “This is not a Samurai.” In that short sentence lies the entire philosophy of his work. The warrior figure is not the portrait of an actual person, but a symbol, an empty form that culture fills with meanings – now devoid of substance. Noguchi’s samurai is not a flesh-and-blood person, but a totem: an emblem of values that once meant something, but today function as decoration, as façade. The armor becomes a uniform worn without conviction – because it’s expected, because it’s tradition, because it has always been that way.

That is precisely why Noguchi’s samurai is a person of the 21st century. He may wear ancient helmets, but underneath are Adidas sneakers. He may pose like a hero, but in his eyes is emptiness. He is a figure frustrated, maladjusted, torn between past and present, between duty and lack of purpose. He seems to march into battle – but no one knows with whom, or why. His life resembles a historical reenactment stripped of meaning, leaving only costume behind.

And yet Noguchi does not ridicule. He does not mock the warrior, but rather pities him. He shows his absurdity, but also his dignity. He reveals the dissonance between appearance and inner life – but without cruel irony. There is a deep tenderness toward the past here, though entirely devoid of illusion. Noguchi does not believe in the grandeur of the samurai ethos, but he also doesn’t treat it as a joke. He treats it as a trace – significant not for what it depicts, but for what it tells us: about our need for meaning, for belonging, for a model to follow.

The central motif of many of Noguchi’s works is the armor – not only as a historical element, but as a metaphor for the psyche of modern humans. Armor protects, but it also restricts. It is both burden and defense. It allows survival, but hinders intimacy. A person in armor cannot be hurt – but cannot embrace another, either. It’s the same with emotions: we hide behind roles, images, status. But underneath, we remain defenseless. And this is what Noguchi’s art speaks of: the tension between strength and fragility, between illusion and truth, between form and emptiness.

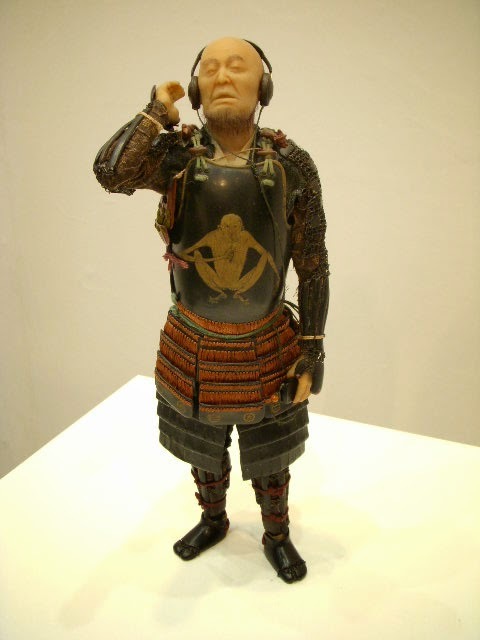

“Chanel Samurai”

「シャネル武者」

– Tetsuya Noguchi, 2009, from a series of independent works exhibited in art galleries,

including SCAI The Bathhouse, Tokyo

An armored warrior with a stern expression sits proudly and stoically in full gear, yet the mon on his abōri – the traditional Japanese family crest – is not the symbol of the Takeda or Tokugawa clan, but… the Chanel logo. Additionally – in the place where one might expect kabuto horns – often a crescent moon or deer antlers (animalistic mimicry was popular in the Sengoku era) – there are stylish, cute kawaii ears. At first glance, one might think this is a simple play on pop culture, but Noguchi, as always, goes much deeper. The accompanying “fictional legend” claims that a certain daimyō granted the warrior’s clan this crest as a symbol of elegance and purity – a completely serious story, fabricated with the full precision of feudal rhetoric. It is precisely this tension between narrative realism and the absurdity of the symbol that makes the work function not as a joke, but as a serious cultural diagnosis.

“Chanel Samurai” is a collision of two forms of symbolic capital: military ethos and contemporary luxury. The mon, once a sign of inherited status, is here replaced by a logo – a modern fetish of recognizability. Noguchi does not mock the samurai but shows how easily our modern aspirations fit into old forms of hierarchy. In his interpretation, the logo becomes a new noble crest, and luxury – a new version of honor. But this samurai, though armed, does not appear victorious – he looks tired and lost in a world where values have been replaced by brands. His armor was made to protect against arrows. But there are no arrows, and he needs to protect himself from losing face. The armor is heavy, beautiful, and hollow – like many modern status symbols – serving no practical function, and only getting in the way.

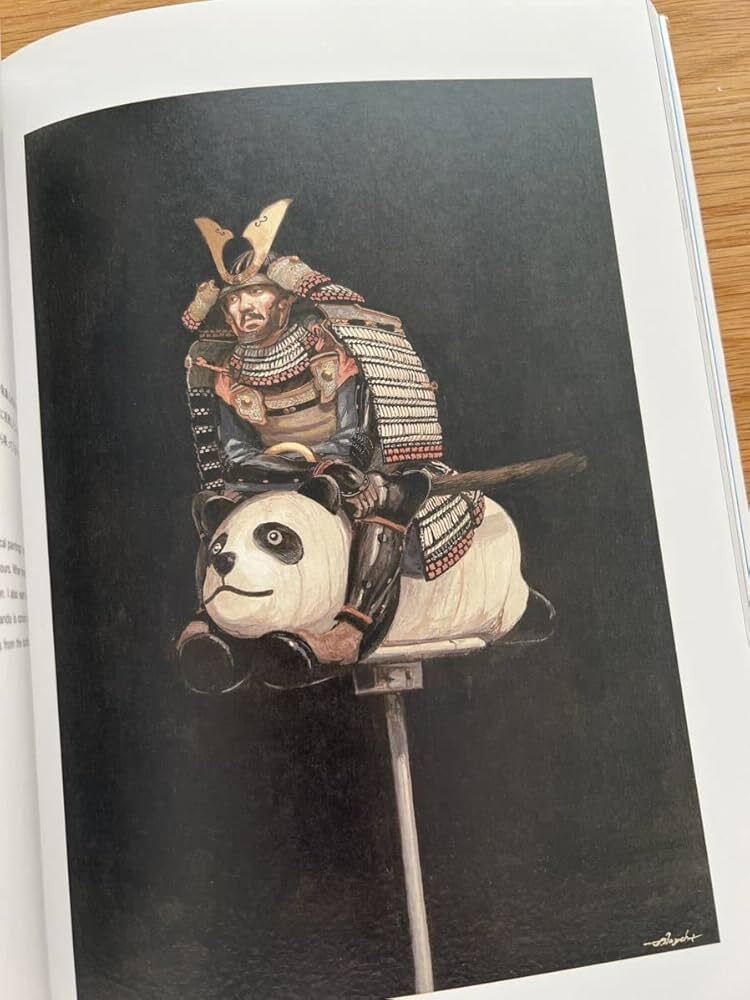

“Pheasant Horse”

キジウマ (Kijiuma)

– Tetsuya Noguchi, 2022, private collection

(exhibited at the Pola Museum Annex)

At first glance, we are dealing with something that resembles a child’s toy or a whimsical sculpture – a samurai in full armor glides forward, riding... a colorful wooden creature on wheels. But it is neither a horse nor a fish – though its shape recalls the carp from koinobori (carp streamers used on Children’s Day). In the artist’s caption, however, we read that it is not a fish but a bird. The title “Kijiuma” is a portmanteau of kiji (pheasant) and uma (horse), thus creating an abstract creature – a symbolic hybrid, a childish steed assembled from Japanese cultural symbols.

This juxtaposition creates a striking psychological and cultural contrast – here is a man in a serious role, reduced to parody by his surroundings. Is it a memory of childhood dreams of heroism, clashing with the grotesqueness of adult life? Or a metaphor for the modern man, who retains the outer armor of a role but mounts a naïve, infantile construction utterly unsuited to reality?

In the context of Noguchi’s other works, it may be read as a commentary on the false cultural and historical identities we construct in the 21st century. The samurai, once a symbol of honor and strength, becomes the rider of a toy illusion – a hero not of war, but of aesthetic styling. Such a “pheasant horse” will carry no one to the battlefield – but it photographs beautifully.

Noguchi is ironic, but not mocking – his art always maintains tenderness toward the human need for myth, even if that myth ultimately veers into the ridiculous. Pheasant, carp, horse – all blend into a colorful vehicle that makes no logical sense, yet holds emotional and cultural resonance. Such is our memory of the past – colorful, awkward, but surprisingly vivid.

“Gradation”

グラデーション

– Tetsuya Noguchi, 2013, private collection, height: 53 cm

An armored figure stands slightly tilted, as if unsure of his stance – neither fully ready for battle nor entirely defenseless. His form evokes that of a real warrior: 河津伊豆守 (Kawazu Izu no Kami), yet it is captured in an aesthetic that deliberately undermines authenticity. Two aspects strike the viewer most. First – the pose. He stands, hesitating, in a very timid manner, evoking not archetypes of masculinity but the stereotype of a modern person full of anxiety, trying to take up as little space as possible, not to stand out, not to impose his presence. And second – the armor itself. Its colors subtly transition from dark to light tones, creating the titular gradient – a stylistic effect that would be entirely impractical in the world of warfare.

This “gradation” is more than an aesthetic device – it symbolizes the blurring of boundaries: between past and present, between warrior and model, between pathos and grotesque. This samurai could be standing at a bus stop – as was noted on the artist’s website – not because it is funny, but because he has been torn from his world. A man in armor that no longer has a reason to exist. And perhaps that’s why he hesitates.

“Man in the Egg”

マン・イン・ジ・エッグ

– Tetsuya Noguchi, ca. 2021, private collection

An armored figure sleeps, slightly hunched, in the iconic “Egg Chair” designed by Arne Jacobsen – like a chick tucked away in a modern shelter. The playful fusion of steel armor and the soft, rounded form of the chair reveals a deeper tension: between hardness and fragility, defense and vulnerability, past and 20th-century design. Noguchi’s commentary – “an egg that protects a hard shell” – reverses nature’s logic: it is not the shell that protects the contents, but the contents hiding from the world in a comfortable egg.

This figure – somewhat embryonic – resembles a modern human armored not with blades but with fears and the need for comfort. The warrior is not awaiting battle. He dreams of peace and quiet. The chair becomes a capsule of psychological isolation, a symbol of retreat into design that aims to shield us from stimuli and worldly chaos. It is an ironic portrait of our era: armed in luxury, curled into introspection, armored not to fight – but so no one will come too close.

“Armoire and Hoodie”

アーマー・アンド・フーディ

– Tetsuya Noguchi, 2020, private collection

A samurai in full armor poses with the nonchalance of an urban fashion model, wearing a gray hoodie from the brand Auralee, whose soft fabric contrasts with the cool gleam of metal. Noguchi juxtaposes two types of “armor”: the historical – meant to protect the body from physical blows – and the contemporary – protecting the personality from the external world through fashion, branding, and style.

This samurai does not wear the hoodie for warmth or after a battle. He wears it for style – because of 5525gallery and the spirit of modern fashion, which has barged into Japanese history as if into a prop warehouse. In this work, Noguchi does not ridicule history, but allows it to be newly clothed – showing that identity can be a layer of styling, as changeable as a seasonal collection.

It’s an ironic view of our times: an age in which one does not become a warrior through trial or code, but through the right look. And an age in which historical armor and a showroom hoodie say exactly the same thing about a person.

“The Dance Man”

ザ・ダンス・マン

- Tetsuya Noguchi, 2022

At first glance – a samurai in a dynamic pose, as if he has just completed a spin or taken the first step in a dance. Noguchi titled this work “The Dance Man”, adding the poetic line: “When I dance, the moon resounds with echo” (「吾が舞えば、照る月響むなり」). But the true power of the scene only reveals itself when we look beyond the armored dancer – at the background, the landscape, the place in which it all unfolds.

For this is not an earthly scene. Not a dance floor, not a palace, not a Japanese court. It is the Moon. The samurai dances in outer space, on the grey regolith, beneath a black sky devoid of atmosphere. Behind him – Earth: familiar, yet distant, suspended in the silence of the void. The dancer stands thus alone, utterly alone – and yet performs a gesture full of grace, expression, and lightness (his posture conveys the low gravity of Earth’s satellite).

Noguchi confronts two realms: tradition and cosmos, art and vacuum, ceremonial gesture and total detachment from the world. This samurai does not dance for an audience, not for tradition, not for memory. He dances for the act of dancing itself – perhaps the last form of beauty left to humankind in a cold, merciless universe.

And there is something tragically beautiful in this gesture. As if Noguchi’s samurai – forever severed from real history – were performing his final dance exactly where the history of humanity ceases to matter. Perhaps it is a manifestation of solitude. Perhaps – of distance. Or perhaps a reminder that even in absolute silence, where no one watches, a gesture can exist – and perhaps have meaning.

Art as an Archaeology of Identity – the Role of Irony and Compassion

Tetsuya Noguchi’s art is neither parody nor tribute – it is a subtle, refined archaeology of identity, in which layers of Japanese history, culture, and myth are unearthed, cleaned, and then... tried on anew. His samurai – clad in hoodies, posing like fashion models, sitting in designer chairs or dancing alone on the Moon’s surface – are not caricatures. They are masks through which something deeper shows through: the question of who we are – and whether we are still anyone at all.

In this world, irony plays the role of compassion rather than mockery. Noguchi does not ridicule the past – rather, he bids it farewell with a melancholic smile, trying to make peace with its departure. His humor is delicate, almost therapeutic. It allows for distance, but does not sever emotion. It is humor as a defense mechanism – a subtle protection against the burden of legacy, against the excessive seriousness of history, which can crush modern sensitivity beneath the weight of its symbols and myths.

There is immense nostalgia in this art. Not for any specific era, but for the very possibility of belonging. Noguchi’s samurai thus becomes a symbol of loss – of what will not return, but also does not wish to leave. He hangs between worlds, balancing between style and meaning, between uniform and nakedness. And perhaps that is why he moves us. Because he is not a samurai from the past – he is our fear, our longing, our homelessness clad in gleaming armor and placed before the mirror of time.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Faulty Man in a Box: The Mechanical Nightmare of Tetsuya Ishida's Paintings

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!