Fur That Earns Billions – Yuru-kyara, or How Every Japanese Town Has Its Own Adorably Awkward Mascot

The Cat Samurai and the Crazy Eel Airplane

These “loose characters” – for that’s the literal translation of yuru-kyara – are seemingly clumsy, huggable creatures. But behind that awkwardness lies surprising marketing precision and a potent dose of local pride. When Kumamon from Kumamoto Prefecture won over the hearts of all Japan and earned the title of “Happiness Manager,” its merchandise market exploded – it still generates billions of yen annually. And many others followed: from TV towers with fatherly faces, to humanoid Austrians on skis, to fruit-bear hybrids with shark teeth. In Japan, everything can have a mascot. And very often, it does.

Today’s article will be a journey through this peculiar land of furry ambassadors. We’ll show how yuru-kyara were born from the need for promotion, how they conquered social media and the hearts of residents, and how – quite seriously – they’re transforming the image of towns and villages. We’ll touch on history and marketing, but also on a question rarely asked in Europe: should a mayor really be dancing next to a pear holding a samurai sword?

What exactly is yuru-kyara? (ゆるキャラ)

Let’s start at the beginning – with that odd-sounding word which, over the past two decades, has taken over Japanese streets, offices, train stations, and the hearts of citizens. Yuru-kyara is a contraction of the Japanese phrase “yurui karakter” – meaning “loose character” or “clumsy hero.” The word yurui (ゆるい) can be translated as “awkward,” “cute,” “soft,” “sloppy,” “uncoordinated,” or even “floppy” – a term which, in Japan, doesn’t necessarily carry negative connotations. Quite the opposite – combined with the English loanword character (キャラクター, shortened to kyara), it creates an expression that perfectly captures the essence of these mascots: characters drawn with a wink, intentionally disproportionate, with oversized heads, stiff limbs, and the obligatory aura of kawaii – the Japanese charm that need not be perfect but must evoke warm feelings.

Over the years, the term became fully embedded in everyday language – to the extent that Japanese people use it not only when talking about mascots but also… about people. When someone behaves in a clumsy, harmlessly awkward way that evokes affection, they might be told they’re like a yuru-kyara. And no one takes offense – because it simply means they’re a “cutie.”

A (not-so-)short history of these adorably oddball creatures

The real yuru-kyara boom didn’t begin until the first decade of the 21st century. Local governments, especially in lesser-known prefectures, began looking for ways to attract tourists and stimulate their economies. And since conventional brochures and ad campaigns weren’t working – they turned to something… fluffier. The earliest characters of this kind, like Sento-kun from Nara (2008), provoked more bewilderment than admiration – this bald boy with deer antlers was meant to promote the 1300th anniversary of the Heijō-kyō capital, but ended up the butt of media jokes. Yet no one was discouraged. Quite the opposite – it was the start of a national obsession.

Today, Japan has over 1,500 official yuru-kyara registered in databases (such as the “Gotōchi chara” catalog). However, according to other estimates, if you count informal, local, and privately created mascots – some made by companies, tourism associations, or schools – the number may reach as high as 4,000.

The mascot economy is a story in itself. According to data from the Ministry of Economy, in 2013 alone, regional mascots generated revenues exceeding 290 billion yen. That’s more than the entire market for Japanese sports-themed manga. Cookbooks with mascots’ favorite recipes are published, as well as coloring books, origami sets, figurine collections, good luck charms, and even… cosmetics endorsed by Gunma-chan (a pony from Gunma).

But this, in fact, is the very essence of yuru-kyara culture: imperfection, awkwardness, and at times even outright nonsense. And the Japanese – like no one else – know how to love that with all their hearts.

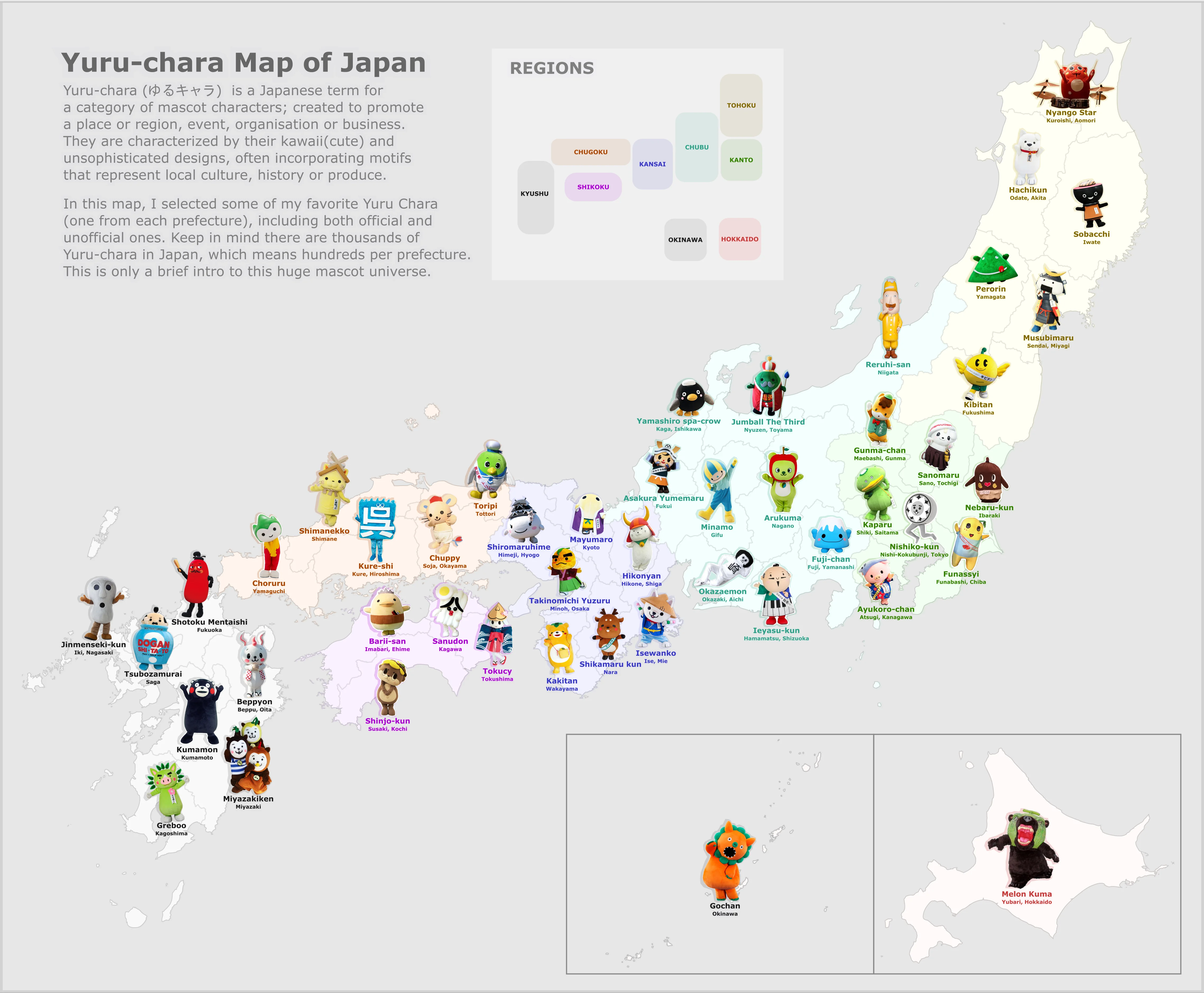

A Map of Japan with Fluffy Commentary

A Parade of Oddballs

Japan is a country where every prefecture, major city, and sometimes even the tiniest mountain village can have its own fluffy representative. Just like a coat of arms or a flag, a yuru-kyara becomes a symbol of local pride – only in a much softer and cuddlier form. These mascots don’t just wave at passersby, hand out flyers, or dance at festivals – they each have their own story, personality, and often even a life philosophy. Below you’ll find selected examples from across Japan – each one a small piece of local culture, hidden in fur, foam, and a wide smile.

Kumamon (“The Black Bear”)

くまモン

Kumamoto Prefecture, 2010

He was created to promote the opening of the Kyūshū Shinkansen line and… exploded in popularity beyond anyone’s expectations. Kumamon brought revenues to the prefecture that exceeded all prior estimates, became a national icon, the protagonist of books, cartoons, and a mountain of merchandise – from keychains to cookies. The Kumamoto authorities gave him the title of “Sales and Happiness Manager,” and his official Instagram account is followed by hundreds of thousands of fans. Kumamon visits schools, trade fairs, Japanese embassies, and has even performed in Paris and Taipei. He’s more than a bear – he’s the archetype of success.

Hikonyan (“Meow from Hikone”)

ひこにゃん

Shiga Prefecture, 2007

He was created for the 400th anniversary of Hikone Castle and quickly won the hearts of tourists. The inspiration came from a legend about a white cat who saved Lord Ii Naotaka by beckoning him with its paw to a temple just before a lightning strike. Since 2007, Hikonyan has drawn crowds of visitors – by day, you can find him in the castle courtyard, where he performs several times daily. Merchandise sales bearing his image bring the city millions of yen annually, and his likeness has even made it into the prestigious Nendoroid collectible figure line. Hikonyan is Hikone’s pride – and a symbol of how adorably history can be told.

Unari-kun (“Eel Roar”)

うなりくん

Chiba Prefecture (Narita), circa 2010

Unari-kun arrived from the planet Unari and settled in Narita after falling in love with its airport. His name is a pun: “unagi” (eel – a local delicacy in Narita) and “Narita” (from the city name, but also nari: the sound or “roar” of passing airplanes). He was officially made the city’s mascot to promote tourism – since many people only pass through on their way to Tokyo. His mission is to make travelers stay a little longer, to taste the yokan, teppōzuke (pickles shaped like rifles!), and experience the local hospitality.

Lerch-san (“Mr. Lerch”)

レルヒさん

Niigata Prefecture, 2011

He is inspired by a real person – Theodor von Lerch, an officer of the Austro-Hungarian army who introduced skiing to Japan in 1911. He was the first to descend the slopes of Niigata and launched a winter sports boom. Lerch-san became the official ambassador for skiing promotion in the prefecture and frequently appears at winter festivals, in advertisements, and at sporting events. Thanks to him, residents are reminded that Niigata is not only about rice and sake – but also about snowy madness with historical roots.

Funassyi (“The Funabashian”)

ふなっしー

Chiba Prefecture (Funabashi), 2011

It was created by a fan of the city of Funabashi as a form of local promotion – but without any official backing from the authorities. Funassyi is a “pear-like monster born from the 274th generation of nashi pear trees” who loves heavy metal, explosions, and… people. Despite having no “official status,” its popularity skyrocketed thanks to social media, original songs, and wild television appearances. It became a celebrity, with its own stores, merchandise, and legions of fans who adore its unorthodox spirit. In a world of well-behaved mascots, Funassyi is a pear-shaped revolution.

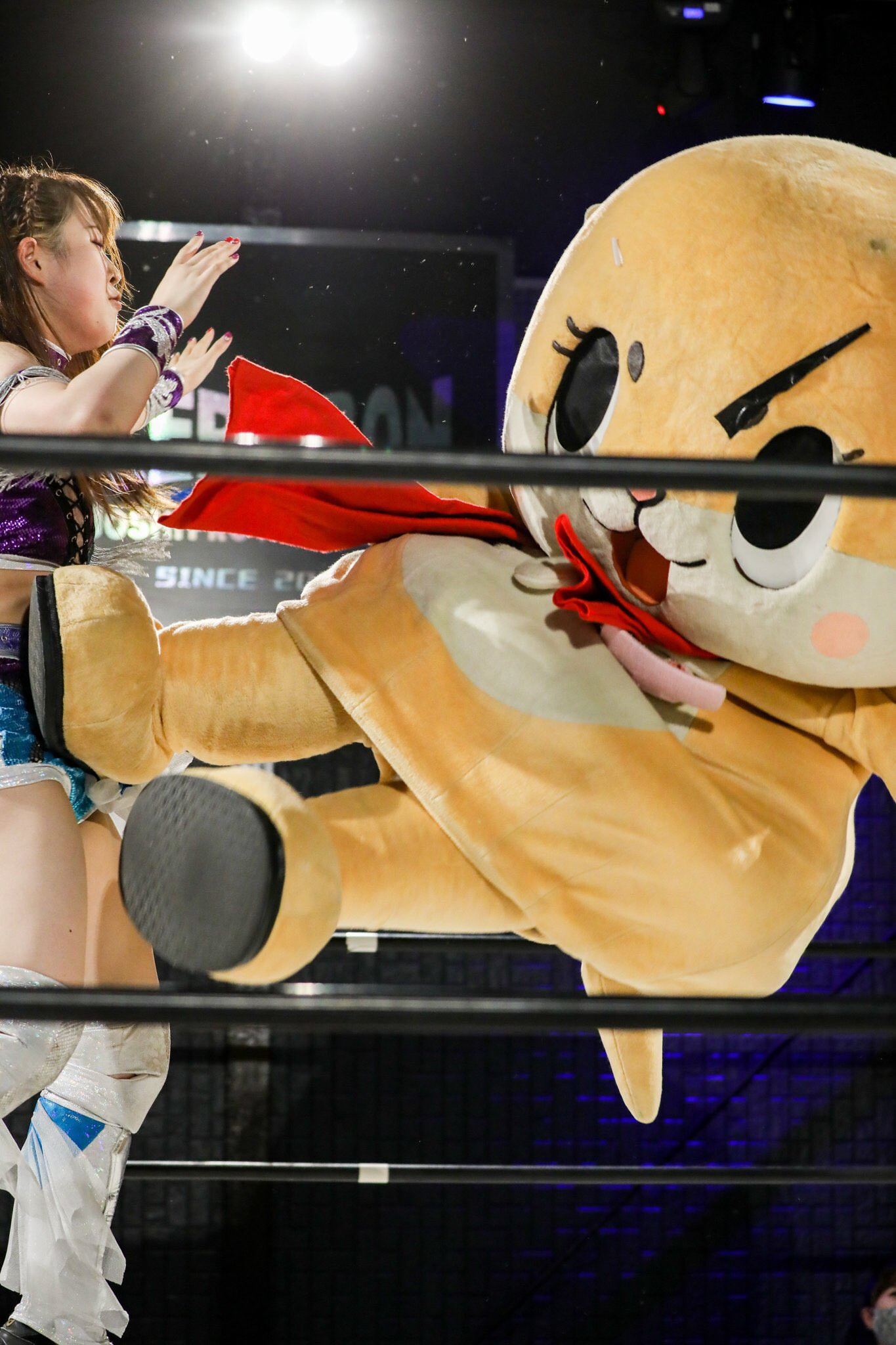

Chiitan☆ (“Sweetie”)

ちぃたん☆

Tokushima, 2017 (unofficial)

Chiitan☆ was created as a “friend” of Tokushima’s official tourism otter mascot, but her antics soon eclipsed the original. Her controversial fame led to conflict with city authorities, who blocked her from further appearances as an “unauthorized mascot.” But that didn’t stop Chiitan☆ — she achieved international fame, got her own cartoon series, and racked up millions of views on Twitter and YouTube. Today, she’s a prime example of a mascot who exploded out of control — and it’s precisely why many people love her.

Gunma-chan (“Gunmaś”)

ぐんまちゃん

Gunma, 1990s, redesigned in 2011

Gunma-chan is one of the most important “regional ambassadors” — appearing on promotional materials, local product packaging, and even in a televised animated series. In 2014, it took first place in the prestigious Yuru-Kyara Grand Prix, cementing its star status. The Gunma prefectural government takes its pony mascot so seriously that it established official usage guidelines for its appearances in the media.

Sento-kun

(“Boy of the Capital Relocation”)

せんとくん

Nara, 2008

Sento-kun was created to commemorate the 1300th anniversary of the relocation of Japan’s capital to Heijō-kyō (present-day Nara) and was intended to combine history, spirituality, and local folklore. Although initially criticized for having an overly religious appearance, he quickly gained a following. Today, he’s a permanent fixture in the landscape of Nara — spotted near temples, at train stations, and in promotional materials for the city. He has sparked considerable controversy, and even now, alongside loyal fans, he has numerous detractors who find his look disturbingly uncanny.

Terebi-tousan (“TV Dad”)

テレビ父さん

Hokkaidō, 2003, unofficial

Although he’s not the official mascot of any public office, in the eyes of Sapporo’s residents, he has long held the status of a local legend. He debuted in 2003 as a promotional figure for the Sapporo TV Tower and quickly began appearing on merchandise, in commercials, and even in a special online sitcom. His name, a clever pun (“Terebi-tōsan” meaning both “Mr. TV Tower” and “TV Dad”), showcases Japan’s love for wordplay.

Jagata-kun (“Spud-Felix”)

じゃがたくん

Hokkaidō (Kutchan), 1997

He was born in 1997 as a symbol of the local potato festival (Jagamatsuri), but over time became a full-fledged ambassador for the town of Kutchan. The name “Jagata” comes from jagaimo (potato) and a stylized suffix -ta (evoking a masculine given name). He’s a prime example of how even the most “down-to-earth” products can become marketing heroes — as long as they have big eyes, a wide smile, and the energy to dance.

Melon Kuma (“Melon Bear”)

メロン熊

Hokkaidō (Yūbari), 2010

Picture this: you’re a cheerful child, traveling with your family to Yūbari for the melon festival, full of joy and hopeful anticipation for a slice of sweet fruit… and then, from around the corner, he jumps out – Melon Kuma. A mascot that looks like someone locked a furious grizzly bear in a tanning booth, waited until the heat cracked its skull, then slapped a rotten melon on its head and said, “Kids will love this.” His eyes look like he’s just seen the winter heating bill in Hokkaidō, and his teeth suggest that melons are merely the appetizer before something more... meaty.

Melon Kuma was born as a desperate attempt by the bankrupt city of Yūbari to draw in tourists (more about this dying town here: Yūbari – the City That Teaches How to Die Slowly – A Vision of the Future for Japan, Poland, and the World?) and decided that scaring people in the street might be a new way to promote local fruit. He was meant to be original and unforgettable – and to be fair: the trauma lingers. Though he looks more like a boss fight from Resident Evil than a festival mascot, he gained a dark popularity online, appeared at conventions, and even had his own line of merchandise – because, after all, Japan is a country where even a melon-induced nightmare can become a celebrity.

Yuru-kyara in Real Life

At first glance, it’s all just fun and games. But for many Japanese regions, yuru-kyara are serious business – both economically and socially. After Kumamon’s success, generating billions of yen from merchandise sales and drawing thousands of tourists to Kumamoto, other prefectures quickly realized that a plush mascot can do more than any glossy brochure. Cities once overlooked in travel guides suddenly became tourist destinations – all for the sake of snapping a selfie with the local hero.

Mascots also foster a sense of community and local pride. Children learn their names in preschool, seniors wear their pins on grocery bags. In smaller towns, they are often the region’s only “celebrity,” representing its people across the country. Instead of a suited official, it’s a grinning mascot that greets guests at festivals, bringing spontaneity and energy through its unpredictable behavior.

Inspiration for Us?

Because though they have soft bellies and trip on stage, at heart they are modern versions of local guardian spirits – kind, present, and full of charm. If you look closely, each one is an invitation to discover something more: a mountain festival, a town with hot springs, an old pilgrimage route. Finding your favorite mascot is like stumbling upon a secret passage – you don’t know where it will lead, but it’s sure to be an adventure.

Can yuru-kyara replace government officials? Perhaps not entirely. But they certainly help humanize them – and remind us that even local administration can be warm, funny, and approachable. And in a country where etiquette and hierarchy can be as stiff as a kimono in the frosts of Yukiguni, such plush relaxation matters more than one might think.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Do you know these plushies? The Global Phenomenon of Milk & Mocha Bears

Tanuki Swinging His Coin Pouch – How Did Japanese Woodblock Artists See This Rascal?

Poetry with Sake – Master Senryū and His Joyfully Malicious Insight

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!