A Lesson with Sei Shōnagon: How to Pause Our Gray Everyday Life, Look at It and Enchant It?

Looking at a Gray Day from a Different Perspective

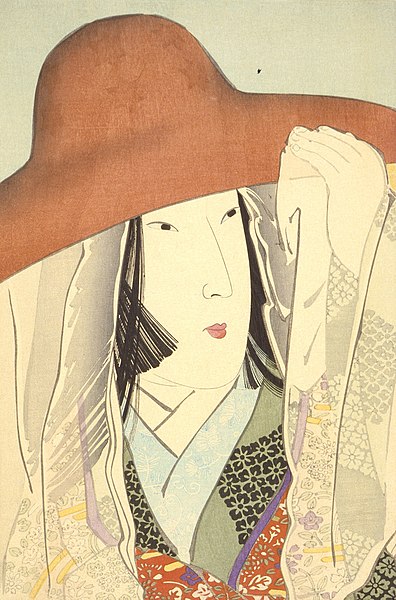

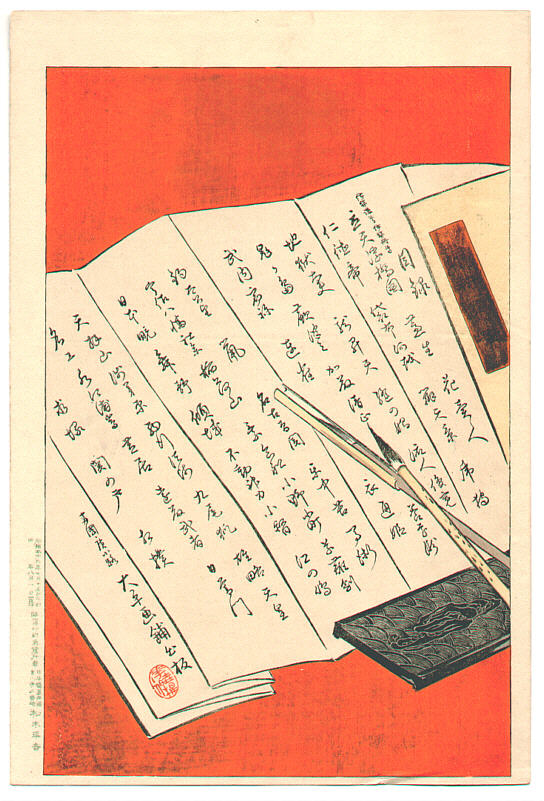

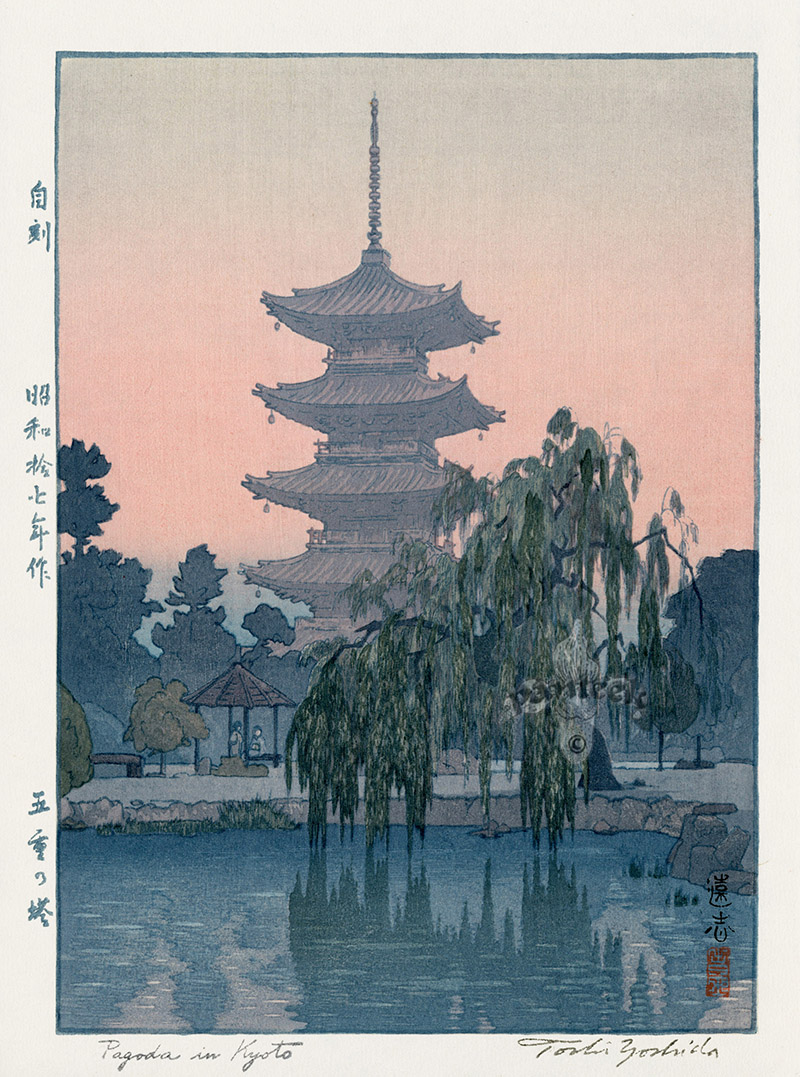

The Life and Works of Sei Shōnagon fall into the pivotal Heian period, considered the classical era of Japanese culture. She is the author of "Makura no Sōshi" ("The Pillow Book" or "Notes from the Pillow"), a work that remains an essential source of knowledge about etiquette, aesthetics, and everyday life at the imperial court in Kyoto (Heian-Kyo).

Considering that human life consists predominantly of ordinary, boring, gray everyday events, the ability to give them depth and beauty seems invaluable. From passages of Sei Shōnagon's work, we learn how to "pause" our gray reality for a moment and look at it from the side, from a different angle, to see its hidden beauty and feel the joy of new discovery or reflection. Today's article will check not only who Sei was and where she lived but also—how she did it.

In What Times Did Sei Shōnagon Live?

It did not take long for Heian-kyō to become the cultural and political center, where court life flourished under the patronage of the Fujiwara family, whose members, like Fujiwara no Michinaga, often served as regents (sesshō or kanpaku) for minor emperors. During this period, literature, calligraphy, and art reached an exceptional level of development, evident in the heritage of the Heian period, which includes the most important works of Japanese (and world) literature, such as "Genji Monogatari" ("The Tale of Genji") by Murasaki Shikibu (about whom we write here: murasaki) and "Makura no Sōshi" by Sei Shōnagon.

During the reign of Fujiwara no Michinaga, who took power in 995 after the death of his brother Fujiwara no Michitaki, the Heian court was at its peak of artistic and cultural creation. Support for art and literature was one of the tools for strengthening the power of the Fujiwara clan, and members of this family often entered into marital relationships with the imperial family, further solidifying their position.

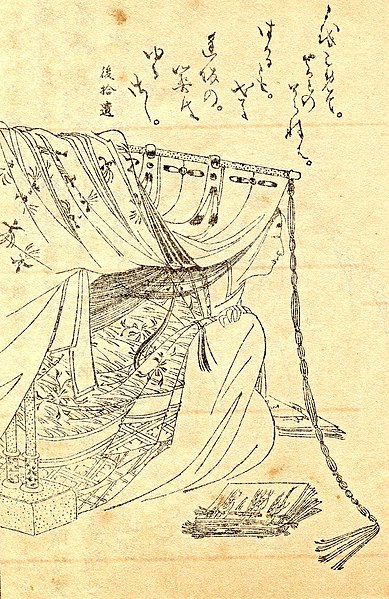

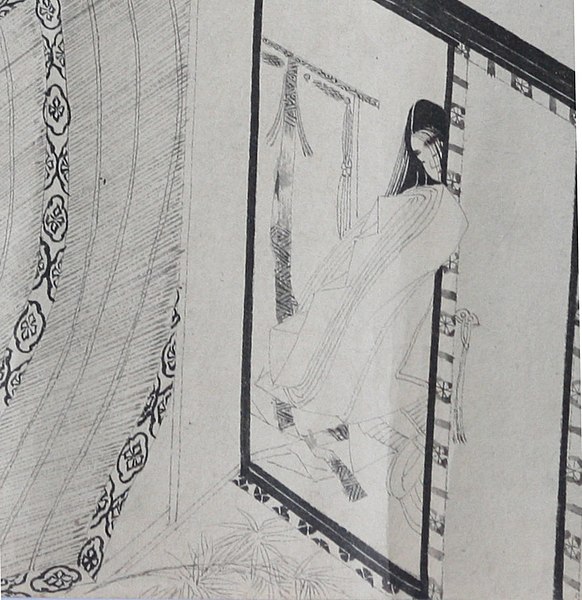

The Life of Sei Shōnagon at the Court of Empress Teishi, the wife of Emperor Ichijō, was filled with events that reflected the complexity and subtlety of the court culture of those times. Her observations and records of daily life provide not only knowledge of art and literature but also a deep insight into the social and cultural life of Heian-kyō. Indeed, it is the main source of knowledge, alongside Genji Monogatari by Murasaki Shikibu, about the life of the elites in the Heian period of Japan.

The Mystery of the Name

Sei Shōnagon is an example of this practice. "Sei" (清) is the Chinese reading of the first character of her family name Kiyohara (清原)—we know from this that she came from the Kiyohara family, known for its literary achievements. The second part, "Shōnagon" (少納言), means "minor counselor," which is the title of a lower-ranking government official. It is interesting because neither her father nor her husband officially held this position. It is possible that this title belonged to another, unidentified family member or was simply a literary fantasy, intended to give her person additional prestige. Like many things from the life of Sei Shōnagon, this remains a mystery of distant history and we may never know.

Sei Shōnagon's name, like her literary legacy, thus becomes a symbol of a certain era and culture where anonymity and artistic freedom go hand in hand, creating a unique, never-to-be-repeated historical portrait of a Heian-era court lady—anonymous, and thus boldly commenting on reality and surroundings.

Life of Sei Shōnagon

Life at the Court of Teishi

We can therefore imagine, based on her descriptions of life in Heian-Kyo, what her day looked like. She began her morning with the dressing ceremony, where amidst the rustling of silk kimonos and discreet conversations with the servants, Sei skillfully composed poems in her head, which she later transcribed onto the pages of her famous work, "Makura no Sōshi." In the palace gardens, filled with blooming plums and golden carp, she often sat with other court ladies, and even the empress, discussing the subtleties of court life and observing the play of light on the surface of the pond, contemplating aesthetic or Buddhist issues.

Relationships with the Empress

These relationships were extremely important as they created a support network, exchange of thoughts, and artistic and literary creativity. For court ladies, such as Sei Shōnagon, close relations with the empress were also a way to enhance their own prestige and influence. Moreover, close and personal relationships with the empress allowed for gaining unique insights and experiences, which they later could use in their literary works – we see this repeatedly in the content of "Makura no Sōshi" by Sei Shōnagon.

Important events at court, such as festivals, celebrations, and ceremonies, were for Sei not just obligations but an inexhaustible source of inspiration. She described them with passion and attention to detail, from the colors of the garments to the emotions of the participants, turning everyday duties into a true work of art.

Her impact on culture and literature was undeniable. "Makura no Sōshi" not only depicted life at the imperial court from the perspective of an intelligent and sensitive woman but also presented her as a chronicler and commentator of her times, who through the prism of personal experiences and observations managed to create a timeless work, full of life and colors.

Rivalry with Murasaki Shikibu

Murasaki Shikibu in her diary describes Sei Shōnagon in a way that can be interpreted as critical. She describes her as a person who is overly confident and arrogant, indicating some tension or at least a lack of sympathy. Additionally, Murasaki accused Sei Shōnagon of superficiality in her work and the use of too many Chinese characters, which at the time was a sign of pretentiousness.

In a literary context, both were also representatives of different styles and genres of literature. Sei Shōnagon is known for "Makura no Sōshi," a collection of essays, letters, and anecdotes, whose form is loose and personal. Murasaki Shikibu, on the other hand, created "Genji Monogatari," the first psychological novel, which formed a coherent whole with a logically arranged plot.

Philosophy of Sei Shōnagon

Beauty in Ordinariness and Everyday Life

In her work "Makura no Sōshi," Sei Shōnagon shares with us her unique view of a life philosophy that celebrates aesthetics and a subtle approach to the world. She teaches us how to see something inspiring, beautiful, and evoking deeper feelings associated with contemplation in ordinary, everyday events and seemingly uninteresting phenomena.

Aesthetics of Everyday Life

In "Makura no Sōshi," we find numerous lists documenting these interests: from the list of "things that quicken the heart," through "things that are elegant" to "things that are irritating." Each of these entries testifies to the author's deep sensitivity to her surroundings and her tendency to reflect on it. Above all, it teaches the attentive reader how to pay attention to these details so that life turns into a constant delight and admiration.

Perception of the World and the Later Concept of Mono no Aware

In her "Makura no Sōshi," she presents a subtle yet deep understanding of the philosophy of mono no aware, although this term was not used until later centuries, in the Edo period. Mono no aware literally means "awareness of things" and is a Japanese aesthetic concept that expresses sensitivity to ephemerality, emphasizing the delicate sadness that comes from the transience of things.

Without structure: Zuihitsu

Furthermore, the term zuihitsu in relation to this work was more frequently used in academic circles, for readers it was simply notes, or diaries.

Lessons in beauty and transience

The brief beauty of blossoming flowers

In one passage from "Makura no Sōshi," Sei Shōnagon describes the sight of blossoming flowers that unexpectedly appear on trees. Although these flowers are symbols of transience, Shōnagon finds something incredibly beautiful and valuable in this fleetingness. She emphasizes that although the flowers quickly fall, the moment of their blooming is filled with deep joy and aesthetic satisfaction. This moment becomes a metaphor for life, which despite its brevity, is full of beautiful and valuable moments, and the awareness of an imminent end further enhances and magnifies its temporary beauty.

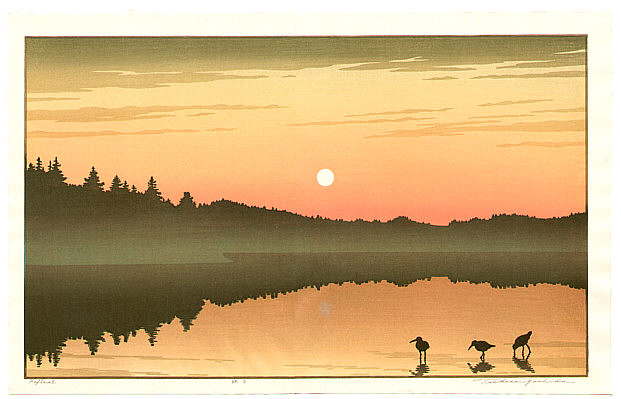

Night observations of the moon

Night observations of the moon

Another important passage found in her notebook pertains to observations of the moon at night. Shōnagon describes the peace and mystery of the night sky, which becomes the backdrop for the brightly shining moon. This contemplation leads to reflections on human life, which, like the phases of the moon, goes through various stages and changes, yet retains its essential essence. In this context, Sei Shōnagon points out how important it is to appreciate each moment and find beauty even in the simplest phenomena of nature.

Wind bringing the scent of flowers

Wind bringing the scent of flowers

Sei Shōnagon also pauses to describe the wind that carries the scent of flowers with it. This experience becomes for her an example of how the senses can be a bridge connecting man with nature. The scent of flowers, carried by the wind, reminds her of the cyclicality of nature and how man is connected to it. This reminder of the inseparable dependency on the natural world is for Shōnagon a way to understand deeper truths about human existence.

Discovering beauty in daily rituals

Discovering beauty in daily rituals

In "Makura no Sōshi," Sei Shōnagon often explores the beauty and significance of daily activities and rituals that took place at the Heian court. One of her well-known entries concerns the subtle and aesthetic observation of dressing, which, although it might seem routine, becomes for Shōnagon a moment full of elegance and significance. She describes how court ladies carefully select their outfits, the color of fabrics, the way they are arranged and tied, reflecting not only their social status but also their personal feelings and aspirations. For Sei Shōnagon, details are important: an outfit that perfectly suits the occasion can attract admiration and praise, while an inappropriate choice can provoke criticism. In her eyes, attire is not just a matter of aesthetics, but also a means of expression and communication. She describes the feeling of satisfaction that arises when everything is meticulously prepared, and her descriptions vividly convey the texture of the fabrics and the atmosphere of the preparations.

Reflections on the changing seasons

Reflections on the changing seasons

Sei Shōnagon often refers to the changing seasons, which she observes from the windows of the imperial palace. In one of the entries, she describes how falling leaves in autumn remind her of the inevitable passing. This change in nature becomes for her an opportunity for philosophical reflections on life and its cyclicality. In her eyes, each season has its unique value and mood, which should be appreciated and from which one can draw inspiration. There is no room here for valuing moods – "more pleasant," "worse." Sei is an observer who, like a sponge, absorbs all the emotions of the mood offered by the environment and savors them.

Waiting for dawn

Waiting for dawn

In another record, Sei Shōnagon describes waiting for dawn, which for her is a time of introspection and contemplation. The silence before sunrise, the gradual brightening of the sky, and the first sounds of birds create an atmosphere of anticipation and new possibilities. From her subtle description, we can infer how Shōnagon uses this moment to reflect on her life and plans for the coming day, or perhaps for the future, in the quiet of the slowly awakening world.

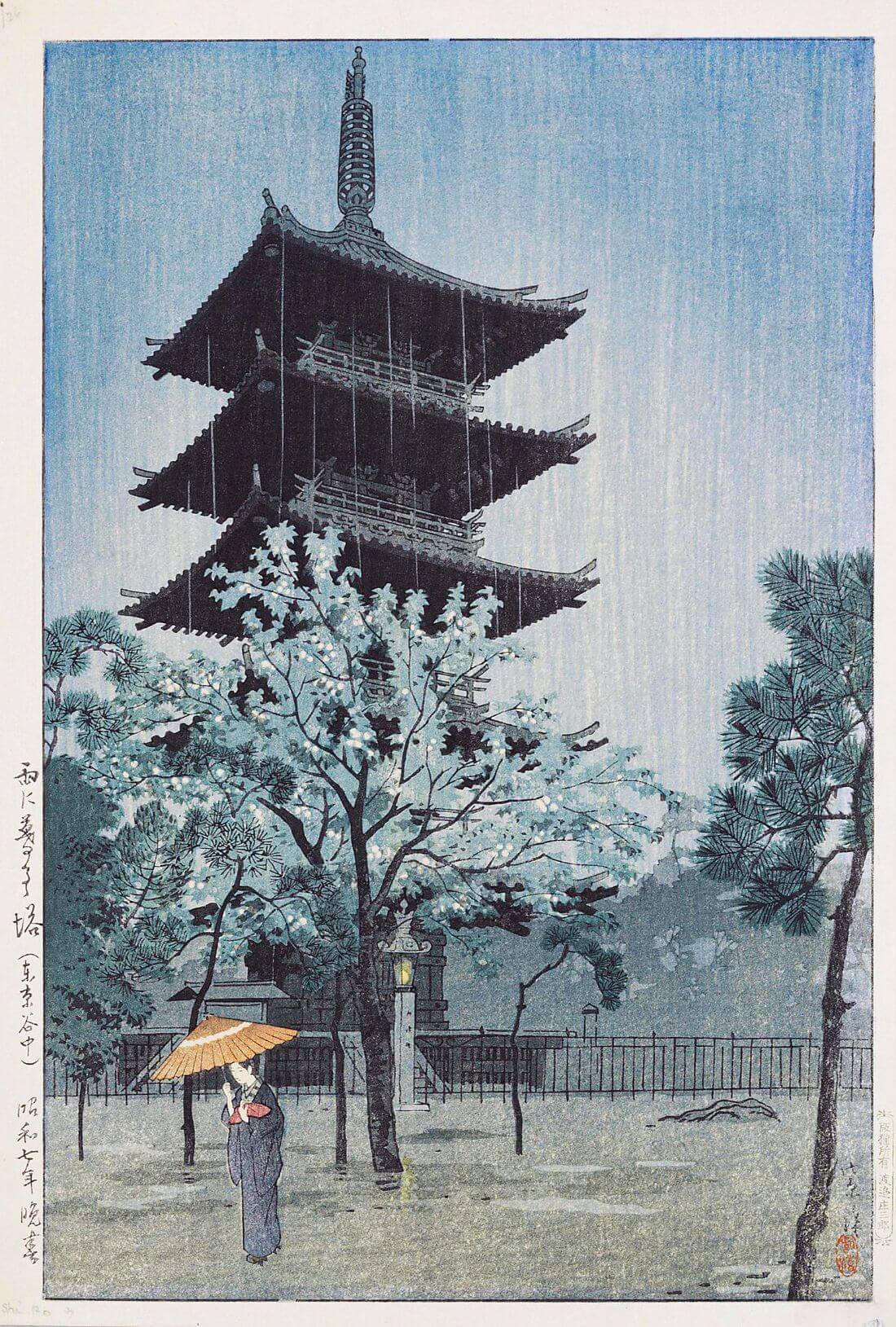

The charms of a rainy day

The charms of a rainy day

In "Makura no Sōshi," Sei Shōnagon often focuses on natural phenomena, including rain - she does so in a way that combines direct observations with personal reflections. She combines the plastic description of rain, for example, gently and rhythmically tapping on the roof of the pavilion, with the description of how the phenomenon fills the poet and courtiers with peace and gentleness. Rain becomes for her not just a physical phenomenon, but an opportunity for introspection and reflection on the transience of life. This perspective is very characteristic of Heian period literature, where natural phenomena were often used as metaphors for deeper truths about human existence.

Sei in pop culture

Sei Shōnagon, although she lived over a thousand years ago, continues to inspire. Her character appears in various media forms today. These contemporary adaptations of her life and works not only pay tribute to her creativity but also facilitate a dialogue between the past and the present, showing how ancient texts can gain new meaning in a modern context.

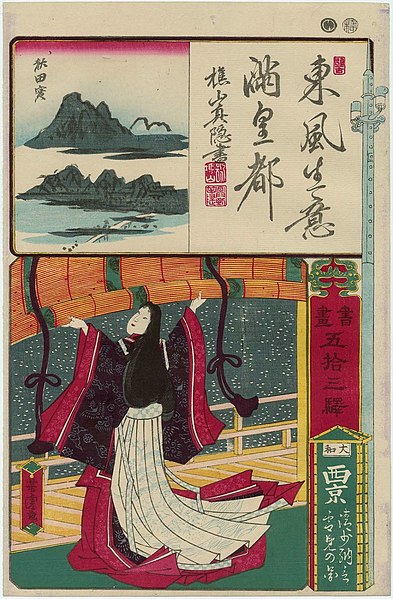

"Chōyaku Hyakunin Isshu: Uta Koi" (2012, directed by Kenichi Kasai)

"Chōyaku Hyakunin Isshu: Uta Koi" (2012, directed by Kenichi Kasai)

This anime interprets classic Japanese poems from the Hyakunin Isshu anthology through the lens of romantic stories. Sei Shōnagon appears as one of the characters, and the series explores her relationships with other poets of that period and her impact on Japanese literature.

"The Pillow Book" (1996, directed by Peter Greenaway)

Although this film is loosely based on "Makura no Sōshi," and the main character - Nagiko (played by Vivian Wu) - is not directly portrayed as Sei Shōnagon, the inspirations from Shōnagon's work are visible. The film combines elements of visual poetry with erotica. Its aesthetics are intended to reflect the spirit of the original "Makura no Sōshi."

In this video game, Sei Shōnagon is one of many writer spirits who fight to protect literature. The character of Sei Shōnagon is portrayed with an emphasis on her intelligence and literary skills, which is consistent with her historical image.

A lesson still relevant

She teaches us how to find beauty and magic in ordinary moments - she enchanted life so that it was a series of beautiful frames, which are not simply cut from the whole - they constitute the whole themselves.

The influence of Sei Shōnagon has crossed the boundaries of Japan, reaching into Western literature and philosophy. In the 20th century, writers such as Virginia Woolf and Jorge Luis Borges expressed appreciation for the zuihitsu form, valuing its loose structure and personal tone, which allows for deep introspection and reflection. Woolf often invoked Sei Shōnagon in her essays as an example of a writer who combined age-old wisdom with a personal perspective on the world around her.

Sei Shōnagon remains a symbol of literary brilliance and extraordinary perception. Her works are reinterpreted in various forms of art, and the lesson she teaches us is still relevant - how to appreciate the subtle beauty of everyday life?

>>SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

The Author of the World's First Novel: Meet the Strong and Stubborn Murasaki Shikibu (Heian, 973)

Hokusai: The Master Who Soothed the Pain of Life's Tragedies in the Quest for Perfection

Japanese Philosophy of Mono no Aware: The Practice of Mindful Being

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Night observations of the moon

Night observations of the moon  Wind bringing the scent of flowers

Wind bringing the scent of flowers  Discovering beauty in daily rituals

Discovering beauty in daily rituals  Reflections on the changing seasons

Reflections on the changing seasons  Waiting for dawn

Waiting for dawn  The charms of a rainy day

The charms of a rainy day  "Chōyaku Hyakunin Isshu: Uta Koi" (2012, directed by Kenichi Kasai)

"Chōyaku Hyakunin Isshu: Uta Koi" (2012, directed by Kenichi Kasai)