"Where is the crisis?"—I ask myself while strolling through the streets of Harajuku.

On paper, it appears to be a tale of decline. Japan—once a paragon of miraculous development, the land of Walkmans, Sony, Toyota, and an automated future—has seen virtually no growth for three decades. GDP barely flutters, the population shrinks year by year, and demographers warn that by the mid-21st century, nearly half the society will be of retirement age. For Western economists, it has long served as a cautionary example: "Don't do as Japan did." And yet—one only needs to walk the streets of Tokyo to see that something doesn't align with this narrative. The cities pulse with modern, healthy life. Trains arrive to the second. Tap water is as pure as spring water. Children walk to school alone. Everything is incredibly clean, and people here live the longest in the world. Housing, relative to income, is among the most affordable globally. Street crime is virtually nonexistent. Something doesn't add up. Where is the collapse, the catastrophe we are warned against? Something eludes the simplicity of charts.

On paper, it appears to be a tale of decline. Japan—once a paragon of miraculous development, the land of Walkmans, Sony, Toyota, and an automated future—has seen virtually no growth for three decades. GDP barely flutters, the population shrinks year by year, and demographers warn that by the mid-21st century, nearly half the society will be of retirement age. For Western economists, it has long served as a cautionary example: "Don't do as Japan did." And yet—one only needs to walk the streets of Tokyo to see that something doesn't align with this narrative. The cities pulse with modern, healthy life. Trains arrive to the second. Tap water is as pure as spring water. Children walk to school alone. Everything is incredibly clean, and people here live the longest in the world. Housing, relative to income, is among the most affordable globally. Street crime is virtually nonexistent. Something doesn't add up. Where is the collapse, the catastrophe we are warned against? Something eludes the simplicity of charts.

Japan hasn't undergone a classic crisis. This isn't a recession marked by unemployment and fear. It's rather a slow transition—unplanned, yet real—into a world without growth. Society didn't revolt, didn't fight for or against reforms. Nor did it forgo comfort and security, but began to learn to live without constant acceleration. Most contemporary countries count GDP growth among their primary national objectives. Is this the only path? This is the paradox of Japan: a country that—without growing—didn't fall. On the contrary, it transformed stagnation into endurance, and endurance into a new rhythm of daily life. Japan didn't create a utopia, but perhaps—unintentionally—became a laboratory of the future. It doesn't offer a ready-made model, but it shows that one can live prosperously by redefining "prosperity."

Japan hasn't undergone a classic crisis. This isn't a recession marked by unemployment and fear. It's rather a slow transition—unplanned, yet real—into a world without growth. Society didn't revolt, didn't fight for or against reforms. Nor did it forgo comfort and security, but began to learn to live without constant acceleration. Most contemporary countries count GDP growth among their primary national objectives. Is this the only path? This is the paradox of Japan: a country that—without growing—didn't fall. On the contrary, it transformed stagnation into endurance, and endurance into a new rhythm of daily life. Japan didn't create a utopia, but perhaps—unintentionally—became a laboratory of the future. It doesn't offer a ready-made model, but it shows that one can live prosperously by redefining "prosperity."

Perhaps, then, the problem doesn't lie with Japan, but with the very concept of "success." Since the 1950s, we've measured it almost exclusively with a single indicator—economic growth. Meanwhile, Japan, perhaps as the first, began to function in a reality where growth ceased to be the central axis of the world. Not by choice, not by ideology—but out of necessity, due to demographic conditions and civilizational saturation. And that's precisely why its case is so fascinating: because it raises questions that are only beginning to penetrate global consciousness. Is development without growth possible? Can a society be healthy, safe, and sensibly organized—even if it doesn't gain GDP points? Is prosperity about quantity, or perhaps about quality?

Perhaps, then, the problem doesn't lie with Japan, but with the very concept of "success." Since the 1950s, we've measured it almost exclusively with a single indicator—economic growth. Meanwhile, Japan, perhaps as the first, began to function in a reality where growth ceased to be the central axis of the world. Not by choice, not by ideology—but out of necessity, due to demographic conditions and civilizational saturation. And that's precisely why its case is so fascinating: because it raises questions that are only beginning to penetrate global consciousness. Is development without growth possible? Can a society be healthy, safe, and sensibly organized—even if it doesn't gain GDP points? Is prosperity about quantity, or perhaps about quality?

A Laboratory of the Future

From the perspective of Western economists, Japan has for years been a cautionary tale—a country that, after the spectacular boom of the 1980s, slipped into three decades of stagnation, deflation, and demographic regression. GDP now grows at a barely noticeable pace—in 2024, by just 0.1% year-on-year (the lowest among G7 countries). The population has been declining steadily since 2008, and in 2023 alone, the number of deaths (1.58 million) exceeded the number of births (727,000) by over 850,000. The median age of the country's residents is already 49.8 years—the highest in the world after Monaco—and forecasts suggest it will soon rise above 60 years.

From the perspective of Western economists, Japan has for years been a cautionary tale—a country that, after the spectacular boom of the 1980s, slipped into three decades of stagnation, deflation, and demographic regression. GDP now grows at a barely noticeable pace—in 2024, by just 0.1% year-on-year (the lowest among G7 countries). The population has been declining steadily since 2008, and in 2023 alone, the number of deaths (1.58 million) exceeded the number of births (727,000) by over 850,000. The median age of the country's residents is already 49.8 years—the highest in the world after Monaco—and forecasts suggest it will soon rise above 60 years.

And yet, Japan hasn't collapsed. On the contrary—it remains the world's fourth-largest economy, with modern infrastructure, functioning public transport, safe streets, a stable housing market, and the highest average life expectancy (over 84 years). It's a country that, despite a chronic "lack of growth," offers its citizens a life free from many afflictions plaguing Western democracies. Homelessness, addictions, or street crime are hard to find there (yes, they exist, of course, but are significantly more marginal). Trains are punctual, streets are clean, children walk to school alone.

And yet, Japan hasn't collapsed. On the contrary—it remains the world's fourth-largest economy, with modern infrastructure, functioning public transport, safe streets, a stable housing market, and the highest average life expectancy (over 84 years). It's a country that, despite a chronic "lack of growth," offers its citizens a life free from many afflictions plaguing Western democracies. Homelessness, addictions, or street crime are hard to find there (yes, they exist, of course, but are significantly more marginal). Trains are punctual, streets are clean, children walk to school alone.

This paradox—life in prosperity without growth—poses a fundamental question to the world: is Japan a harbinger of a transformation of the capitalist model, which has begun to overheat in excessive consumption? Or is it rather a precursor of a new order—a post-growth society that, instead of chasing further GDP percentage points, learns to function in balance?

Japan may be the first highly developed country that has truly settled into the "post-growth" era. Its case is no longer just an exception to the rule—it increasingly appears as a foretaste of the future, into which other developed countries are inevitably heading: aging, exhausted by the pace of life, mired in climate and infrastructure crises. And although the answers are not yet obvious, it is Japan that has become a quiet civilizational laboratory—a place where the world can observe what happens when growth ends, but life does not.

Japan may be the first highly developed country that has truly settled into the "post-growth" era. Its case is no longer just an exception to the rule—it increasingly appears as a foretaste of the future, into which other developed countries are inevitably heading: aging, exhausted by the pace of life, mired in climate and infrastructure crises. And although the answers are not yet obvious, it is Japan that has become a quiet civilizational laboratory—a place where the world can observe what happens when growth ends, but life does not.

Three Decades Without Growth—What Really Happened?

Three Decades Without Growth—What Really Happened?

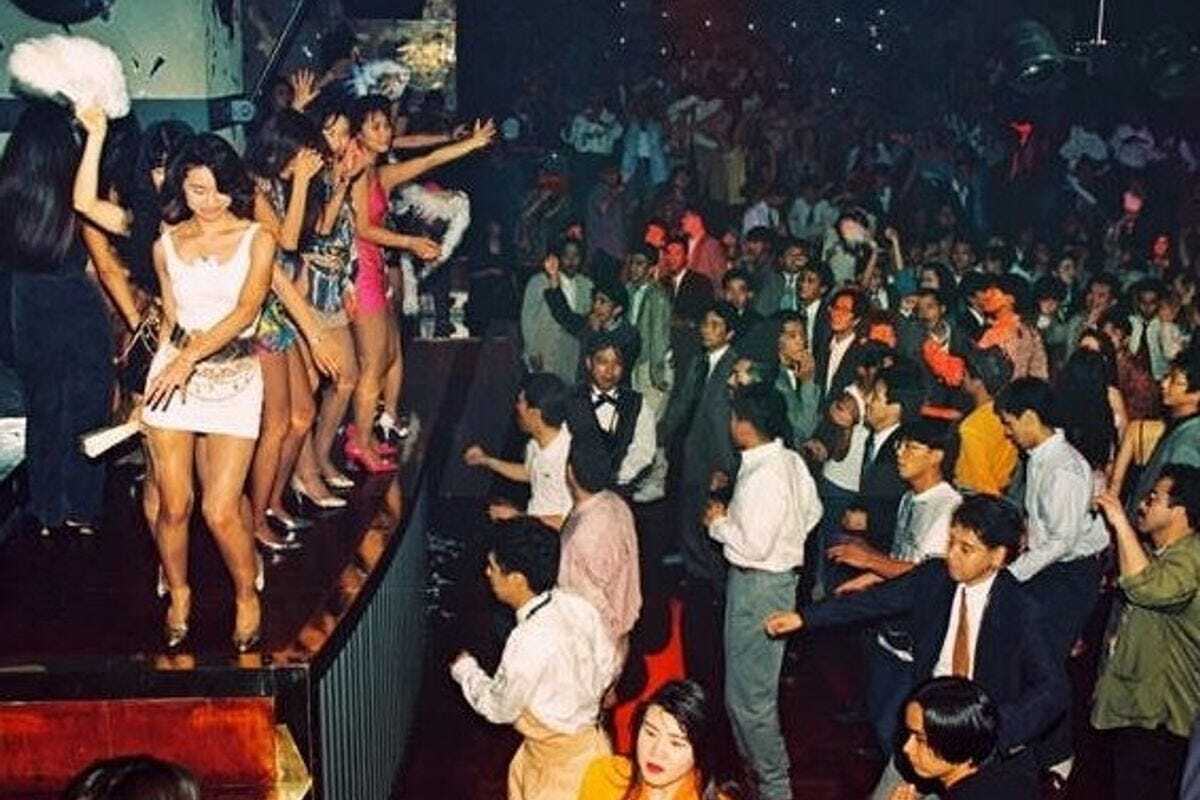

Even in the 1980s, the world looked at Japan with a mix of admiration and apprehension. The birth of Walkmans, perfect cameras, Toyota's export dominance, Sony, Nikon—all symbolized the Japanese miracle economy, which, after World War II, achieved one of the most spectacular civilizational leaps of the 20th century. In 1968, Japan surpassed West Germany to become the world's second-largest economy. By the end of the decade, it was believed to be the country of the future. And then came winter.

In 1990, a gigantic speculative bubble burst, inflated by years of excess capital, cheap loans, and frenzied real estate investments. At its peak, the land beneath the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was worth more than all of California. The Nikkei index reached a staggering 38,915 points—then collapsed. Within months, Japan lost trillions of dollars in market value, and the banking system became entangled in a web of bad debts. The future unexpectedly came to a halt.

However, Japan didn't choose shock therapy. Instead of a wave of bankruptcies and rapid reforms, something else emerged: endurance. Banks didn't want—or perhaps couldn't—acknowledge losses. As a result, throughout the 1990s and most of the 2000s, thousands of so-called "zombie firms"—unprofitable enterprises that survived solely thanks to continuous loans rolled over by banks, unable to grow but deemed too "socially necessary" to let fail—were kept alive. This system ensured employment and social peace but blocked creative destruction, the mechanism that, in a healthy economy, allows the new to replace the old.

However, Japan didn't choose shock therapy. Instead of a wave of bankruptcies and rapid reforms, something else emerged: endurance. Banks didn't want—or perhaps couldn't—acknowledge losses. As a result, throughout the 1990s and most of the 2000s, thousands of so-called "zombie firms"—unprofitable enterprises that survived solely thanks to continuous loans rolled over by banks, unable to grow but deemed too "socially necessary" to let fail—were kept alive. This system ensured employment and social peace but blocked creative destruction, the mechanism that, in a healthy economy, allows the new to replace the old.

Added to this was a factor that is now becoming a global topic—demography. Japanese society began to age faster than any other in the world. The number of births in 2023 fell to 727,277—the lowest level in recorded history. Meanwhile, the number of deaths exceeded 1.58 million. Since 2011, Japan has been losing residents every year. A declining number of people of working age means a smaller labor supply, lower consumption, and reduced growth potential.

Added to this was a factor that is now becoming a global topic—demography. Japanese society began to age faster than any other in the world. The number of births in 2023 fell to 727,277—the lowest level in recorded history. Meanwhile, the number of deaths exceeded 1.58 million. Since 2011, Japan has been losing residents every year. A declining number of people of working age means a smaller labor supply, lower consumption, and reduced growth potential.

In real terms, Japan's GDP grew at an average rate of less than 0.25% annually between 2000 and 2019—nearly ten times slower than in the United States. Gross domestic product per capita also remained stagnant. Even when considering only those of working age, Japan still fares poorly—lagging not only behind South Korea or Singapore but also Italy and Spain. Moreover, innovation—measured, for example, by the number of patents—also began to decline in parallel with the shrinking population.

And this wasn't a recession. It was a prolonged drift—a state of suspension between what was and what has not yet come. In many countries, such stagnation would be the beginning of a deep social crisis. In Japan, however, it transformed into something else: a survival model that, somewhat unexpectedly, began to resemble a new form of normalcy.

But what price is paid for it—and is it merely a cost, or perhaps an investment in another world? What is being created before our eyes?

But has Japan really “lost”?

On economic charts, Japan has for decades appeared as a shadow of its former self. Near-zero growth, demographic stagnation, a protracted stretch of “lost decades.” And yet—walking through the streets of Tokyo, one can’t shake the feeling that something doesn’t align with this narrative. Trains arrive with second-level precision. Tap water is as pure as a mountain spring. Street crime is virtually nonexistent. Hospitals operate efficiently—more so than in most parts of the world—and the healthcare system covers nearly all citizens. Life expectancy in Japan exceeds 84 years—one of the highest rates on Earth.

On economic charts, Japan has for decades appeared as a shadow of its former self. Near-zero growth, demographic stagnation, a protracted stretch of “lost decades.” And yet—walking through the streets of Tokyo, one can’t shake the feeling that something doesn’t align with this narrative. Trains arrive with second-level precision. Tap water is as pure as a mountain spring. Street crime is virtually nonexistent. Hospitals operate efficiently—more so than in most parts of the world—and the healthcare system covers nearly all citizens. Life expectancy in Japan exceeds 84 years—one of the highest rates on Earth.

Paradoxically, despite years of GDP stagnation, quality of life in Japan has not only been maintained—it surpasses that of many other highly developed countries in numerous aspects. Japan remains one of the cleanest and safest nations in the world. Public spaces—parks, temples, streets—function here with an extraordinary concern for aesthetics and order. Although part of the society suffers from overwork, recent years have also witnessed new trends: a shift away from excessive hours, growing emphasis on work-life balance, the rising popularity of remote work and shorter workweeks. Yes, even though terms like karoshi originated in Japan, they are now fading. During the pandemic, many Japanese people spent more time at home for the first time in years—and began to ask: “Why were we rushing so much? What for?”

Paradoxically, despite years of GDP stagnation, quality of life in Japan has not only been maintained—it surpasses that of many other highly developed countries in numerous aspects. Japan remains one of the cleanest and safest nations in the world. Public spaces—parks, temples, streets—function here with an extraordinary concern for aesthetics and order. Although part of the society suffers from overwork, recent years have also witnessed new trends: a shift away from excessive hours, growing emphasis on work-life balance, the rising popularity of remote work and shorter workweeks. Yes, even though terms like karoshi originated in Japan, they are now fading. During the pandemic, many Japanese people spent more time at home for the first time in years—and began to ask: “Why were we rushing so much? What for?”

Although Japan is no longer the global leader in consumer electronics, its companies now dominate what’s known as the upstream—advanced components and materials essential to global supply chains. The country holds nearly 100% of the world market share for certain specialized chemicals, lenses, and materials used in lithography. This is the “invisible Japan,” hidden inside the products of other companies—quiet, but indispensable.

Although Japan is no longer the global leader in consumer electronics, its companies now dominate what’s known as the upstream—advanced components and materials essential to global supply chains. The country holds nearly 100% of the world market share for certain specialized chemicals, lenses, and materials used in lithography. This is the “invisible Japan,” hidden inside the products of other companies—quiet, but indispensable.

It’s also worth looking at the housing market, which in many developed countries has become a source of inequality and frustration. Japan is one of the few nations that has effectively addressed housing shortages. In Tokyo, a city of 14 million people, there is no crisis of housing availability nor a rapid price surge, and the price-to-income ratio remains among the lowest in the OECD. The secret? A simple, national zoning system with just 12 building categories and flexible regulations that allow new housing to be built where it’s needed. There are also no Western-style “procedural” environmental barriers that block investments for years.

Japan has not lost—it has chosen persistence, adaptation, and balance instead of an ambition-fueled march toward endless growth. It may no longer arouse the envy of global investors—but it is increasingly sparking the interest of those who begin to question whether the 20th-century development model can be sustained much longer.

Kohei Saitō and the Philosophy of Degrowth – Made in Japan

While the world of economics still seems to revolve around the mantra of “more, faster, further,” a voice from Japan offers something entirely different—calm, balanced, yet radical. It belongs to Kohei Saitō, a Japanese philosopher and next-generation economist who, in 2020, published the book Capital in the Anthropocene (資本主義とエコロジーの未来)—modest in appearance but explosive in content. Despite its academic language and subversive theses, it sold over 500,000 copies in Japan—making it one of the country’s greatest philosophical bestsellers of the 21st century. In 2024, the English translation appeared under the title Slow Down: The Degrowth Manifesto.

While the world of economics still seems to revolve around the mantra of “more, faster, further,” a voice from Japan offers something entirely different—calm, balanced, yet radical. It belongs to Kohei Saitō, a Japanese philosopher and next-generation economist who, in 2020, published the book Capital in the Anthropocene (資本主義とエコロジーの未来)—modest in appearance but explosive in content. Despite its academic language and subversive theses, it sold over 500,000 copies in Japan—making it one of the country’s greatest philosophical bestsellers of the 21st century. In 2024, the English translation appeared under the title Slow Down: The Degrowth Manifesto.

Kohei Saitō is not a classic climate activist. He is a philosopher raised on Marx and the German academic tradition who—also inspired by the Fukushima disaster and disillusioned with the myth of “green capitalism”—undertook a reinterpretation of Marx’s thought with the ecological crisis in mind. At the core of his reflection lies the concept of the “metabolic rift”—a forgotten idea from Marx’s late notes that describes the rupture between human productive activity and nature’s cyclical balance. For Saitō, this is the heart of the modern crisis—the root of planetary destruction and a spiritual severing of humans from the natural world.

In his view, capitalism not only exploits people—it also cuts them off from their environment, transforming nature into a raw resource and society into an insatiable market. Saitō proposes a system of degrowth communism—where instead of measuring success by GDP growth, society focuses on reducing inequality, securing basic needs, and limiting production to what is essential and shared. Abundance—not in the sense of villas and private jets, but in the form of guaranteed access to health, education, housing, water, and energy.

In his view, capitalism not only exploits people—it also cuts them off from their environment, transforming nature into a raw resource and society into an insatiable market. Saitō proposes a system of degrowth communism—where instead of measuring success by GDP growth, society focuses on reducing inequality, securing basic needs, and limiting production to what is essential and shared. Abundance—not in the sense of villas and private jets, but in the form of guaranteed access to health, education, housing, water, and energy.

Does this sound utopian? Perhaps—but that does not make it a naïve utopia. Saitō is not calling for a 20th-century-style revolution, nor does he dream of a centralized five-year plan. On the contrary—his proposals are concrete, evolutionary, and realistic: taxing the wealthy, reducing unnecessary consumption (e.g., private jets, luxury yachts), shortening the workweek, investing in shared and ecological infrastructure, and developing local democracy. In Japan, he initiated the creation of the Common Forest Foundation, which buys forests around Mount Takao to protect them from urbanization as “common goods.”

What’s most interesting—it is not just theory, but something that resonates with Japan’s younger generation. The book was not a hit among professors, but among thirty- and forty-year-olds tired of a life of constant hurry and limited prospects. The COVID-19 pandemic struck Japan as a moment of stillness—people began to ask: Do we really need so many work hours? So many clothes? So many commutes? Saitō helped them name what they were beginning to intuitively sense: that another way of living is possible.

What’s most interesting—it is not just theory, but something that resonates with Japan’s younger generation. The book was not a hit among professors, but among thirty- and forty-year-olds tired of a life of constant hurry and limited prospects. The COVID-19 pandemic struck Japan as a moment of stillness—people began to ask: Do we really need so many work hours? So many clothes? So many commutes? Saitō helped them name what they were beginning to intuitively sense: that another way of living is possible.

A key distinction in his thinking is the one between recession and conscious degrowth. Recession is chaos, unemployment, anxiety, and disintegration. Degrowth is a decision, a plan, a transition—from overproduction and fear to sharing and balance. It is not a crisis but a shift in priorities. Japan—as Saitō argues—is already in a place without growth. The question is not “whether,” but “how”—and whether we can turn this into a value rather than a shameful anomaly.

A key distinction in his thinking is the one between recession and conscious degrowth. Recession is chaos, unemployment, anxiety, and disintegration. Degrowth is a decision, a plan, a transition—from overproduction and fear to sharing and balance. It is not a crisis but a shift in priorities. Japan—as Saitō argues—is already in a place without growth. The question is not “whether,” but “how”—and whether we can turn this into a value rather than a shameful anomaly.

His proposal is not a finished system, but an invitation to rethink prosperity, time, work, and the planet. And perhaps that is precisely why so many Japanese have begun to treat it not as a manifesto, but as the beginning of a conversation about the future they’ve already begun to live. For we must remember: what becomes of an idea depends on the soil in which it takes root. Is it the explosive social chaos of early 20th-century poverty and illiteracy, or the aged, educated, and disciplined society of 21st-century Japan?

Daubts

It is no coincidence that Japan has become the place where degrowth ideas have found their fullest expression. For centuries, this country has practiced life within limits—its insular nature, scarce natural resources, and frequent natural disasters have fostered a culture of frugality, planning, and respect for life’s cycles. During the Edo period (1603–1868), before the West began to dream of industrial growth, Japan had already created a society based on ecological balance: wood was recycled, cities like Edo (today’s Tokyo) functioned through closed-loop waste systems, and production was based on local sources and moderation.

It is no coincidence that Japan has become the place where degrowth ideas have found their fullest expression. For centuries, this country has practiced life within limits—its insular nature, scarce natural resources, and frequent natural disasters have fostered a culture of frugality, planning, and respect for life’s cycles. During the Edo period (1603–1868), before the West began to dream of industrial growth, Japan had already created a society based on ecological balance: wood was recycled, cities like Edo (today’s Tokyo) functioned through closed-loop waste systems, and production was based on local sources and moderation.

The philosophy of shintō, with its belief that spirits (kami) can inhabit not only mountains and forests, but also stones, tools, and even everyday objects, introduced a deep respect for matter into daily life. Buddhism, meanwhile, offered the ideas of impermanence and restraint as paths to inner peace. Modern Japan—though concreted over and globalized—still bears these echoes: in temples tucked between skyscrapers, in meticulously tended gardens, in the custom of not discarding tools without first “thanking” them.

The philosophy of shintō, with its belief that spirits (kami) can inhabit not only mountains and forests, but also stones, tools, and even everyday objects, introduced a deep respect for matter into daily life. Buddhism, meanwhile, offered the ideas of impermanence and restraint as paths to inner peace. Modern Japan—though concreted over and globalized—still bears these echoes: in temples tucked between skyscrapers, in meticulously tended gardens, in the custom of not discarding tools without first “thanking” them.

Japanese philosopher Takeshi Umehara called all of this a “forest civilization” — the antithesis of the Western “civilization of desert and steel.” In his view, Japan grew from a myth of coexistence with nature, rather than its domination. This is not about idealizing the past, but about recognizing that there is an alternative way of being in the world — one that does not rely on boundless expansion. It is precisely this spiritual, yet practical legacy that is today becoming an unexpected point of reference for modern degrowth concepts.

But this picture is not without its flaws.

Japan is no paradise — it is a real country, full of contradictions. The absence of growth has its price: real wages have remained virtually stagnant for years, which for many young people means living on the edge of financial security. Professional and social mobility remains limited — the system of lifetime employment is giving way to precarious forms of labor, but without providing new pathways for advancement. In many sectors of the economy, innovation has slowed, and the conservatism of institutions makes structural reform tentative and sluggish.

Japan is no paradise — it is a real country, full of contradictions. The absence of growth has its price: real wages have remained virtually stagnant for years, which for many young people means living on the edge of financial security. Professional and social mobility remains limited — the system of lifetime employment is giving way to precarious forms of labor, but without providing new pathways for advancement. In many sectors of the economy, innovation has slowed, and the conservatism of institutions makes structural reform tentative and sluggish.

Added to this is the problem of zombie companies which — instead of collapsing — persist thanks to cheap credit and banking protectionism, thereby blocking the flow of capital and talent into more dynamic areas. All of this means that much of the younger generation’s potential may be wasted — not due to a lack of skills, but because of a lack of structural flexibility.

Added to this is the problem of zombie companies which — instead of collapsing — persist thanks to cheap credit and banking protectionism, thereby blocking the flow of capital and talent into more dynamic areas. All of this means that much of the younger generation’s potential may be wasted — not due to a lack of skills, but because of a lack of structural flexibility.

One of Japan’s greatest challenges remains its reluctance to embrace immigration. In the face of a dramatic population decline — in 2023 alone, the country lost a net 850,000 people — opening up to greater migration could mitigate the effects of demographic weakening. And yet Japan remains cautious, even distrustful of this path. On one hand, this is understandable — its social order, tranquility, and cleanliness are sources of pride and security. On the other — too strong an attachment to a homogeneous social structure may, in the long run, hinder adaptability.

Finally — is the culture of social order, which underpins everyday life in Japan, also a barrier to bolder transformations? Consensus, non-confrontation, respect for hierarchy — these are all valuable qualities, but they can also slow down responses to change as its pace accelerates. Like in aikidō — energy can be channeled into smooth movement, but only when it is received, not blocked.

Finally — is the culture of social order, which underpins everyday life in Japan, also a barrier to bolder transformations? Consensus, non-confrontation, respect for hierarchy — these are all valuable qualities, but they can also slow down responses to change as its pace accelerates. Like in aikidō — energy can be channeled into smooth movement, but only when it is received, not blocked.

Japan does not offer a ready-made recipe for the future. It is a laboratory — full of mistakes, experiments, and compromises. But perhaps it is precisely in this imperfection that its strength lies: it shows that degrowth is not a utopia without shadows, but a path — full of trials, adjustments, and reflection.

What can — and should not — the world learn from Japan?

There is no single model for the future. Japan makes no such claim — no one suggests that it has discovered a universal formula for a post-growth order that could be copied in Europe, America, or anywhere else. Its experience is not a ready-made template, but a story of a nation that, out of necessity, learned to live in a world without growth — and to make a lifestyle out of it, rather than a catastrophe. It is more a quiet inspiration than an exportable model; it offers more calm than ambition.

There is no single model for the future. Japan makes no such claim — no one suggests that it has discovered a universal formula for a post-growth order that could be copied in Europe, America, or anywhere else. Its experience is not a ready-made template, but a story of a nation that, out of necessity, learned to live in a world without growth — and to make a lifestyle out of it, rather than a catastrophe. It is more a quiet inspiration than an exportable model; it offers more calm than ambition.

At a time when many Western countries are experiencing fatigue from constant acceleration — the pace of work, production, technological change, and the unending race toward higher GDP — the lessons from Japan are invaluable. First: quality over quantity. Japanese cities are not great because of their size, but because of the intensity of experience — the architectural details, the availability of services, the meticulousness of execution. The same applies to everyday life: even a simple act like drinking tea can possess the quality of ritual when enriched with attentiveness. The Japanese railway is not a source of national pride because it is the fastest, but because it functions with unwavering precision and a culture of care for the passenger.

Second: stability over speed. Where Europe and the USA often respond with abrupt cuts, sudden reforms, and cyclical crises, Japan has chosen the path of endurance. Yes, that endurance has often been frustrating — full of delays and conservatism. But at the same time, it has preserved the continuity of institutions, social relations, and infrastructure that today make Japanese life safe and predictable.

Second: stability over speed. Where Europe and the USA often respond with abrupt cuts, sudden reforms, and cyclical crises, Japan has chosen the path of endurance. Yes, that endurance has often been frustrating — full of delays and conservatism. But at the same time, it has preserved the continuity of institutions, social relations, and infrastructure that today make Japanese life safe and predictable.

There is also a deeper lesson: social values, not just economic ones, should help define prosperity. In Japan, it has long been understood that a good life is not only about having more money, but about less stress, less noise, less violence. That prosperity also means clean air, safe streets, low housing costs, a culture of trust, and access to public transportation that does not require car ownership.

Perhaps the greatest mistake of the West was to equate “affluence” with “unlimited consumption.” Meanwhile, the Japanese experience teaches that no-growth does not have to mean deprivation — only a redefinition of what it means to be full. Instead of endlessly enlarging the plate, one can learn to savor the taste.

Perhaps the greatest mistake of the West was to equate “affluence” with “unlimited consumption.” Meanwhile, the Japanese experience teaches that no-growth does not have to mean deprivation — only a redefinition of what it means to be full. Instead of endlessly enlarging the plate, one can learn to savor the taste.

But a word of caution: Japan is not perfect — and that is precisely why its example is so valuable. It shows that degrowth is not a utopia, but a complex compromise. Low wages, a declining population, immigration barriers, and institutional conservatism are real challenges. And that is why the world should not copy Japan — but understand it. Draw from its wisdom of balance, without falling into oversimplified narratives. This is not a story about “the end of history” — but about a change in direction. And about the idea that one does not always need to run to move forward.

Will Japan become the first post-growth country?

If anywhere in the world the conditions exist to consciously and peacefully enter the era “after growth,” it is in Japan. The infrastructure is already there: a reliable railway, low energy consumption per capita, cities with high density and low emissions. The culture of daily life also supports it: respect for nature, an ethos of moderation, care for detail, the ability to find beauty in the ordinary and repetitive. A society accustomed to stability, to endurance without fireworks. These are not slogans, but real foundations upon which a new way of thinking about prosperity can be built.

If anywhere in the world the conditions exist to consciously and peacefully enter the era “after growth,” it is in Japan. The infrastructure is already there: a reliable railway, low energy consumption per capita, cities with high density and low emissions. The culture of daily life also supports it: respect for nature, an ethos of moderation, care for detail, the ability to find beauty in the ordinary and repetitive. A society accustomed to stability, to endurance without fireworks. These are not slogans, but real foundations upon which a new way of thinking about prosperity can be built.

But there are also barriers — and they must not be ignored. Chief among them: demography. An aging population and shrinking numbers of young people present a challenge not only to the economy, but to the welfare system, education, and social cohesion. Added to that is political conservatism, which often blocks bolder reforms and resists overly daring change. And also the lack of a single, coherent, communal vision of degrowth — one that could unite different social groups and build hope, rather than merely manage stagnation.

But there are also barriers — and they must not be ignored. Chief among them: demography. An aging population and shrinking numbers of young people present a challenge not only to the economy, but to the welfare system, education, and social cohesion. Added to that is political conservatism, which often blocks bolder reforms and resists overly daring change. And also the lack of a single, coherent, communal vision of degrowth — one that could unite different social groups and build hope, rather than merely manage stagnation.

Even so, Japan may be the closest to touching a future that awaits all highly developed nations. If not Japan — then who? The United States? Europe in the midst of an identity crisis? China, still obsessed with growth? Japan, though full of contradictions, may be the most credible candidate to become the first society that does not so much abandon growth as transform it into something new: qualitative, spiritual, ecological, and communal development.

The future will not arrive suddenly. It will not be a revolution, but an evolution — slow, sometimes imperceptible, but more enduring than all great transformations driven by slogans and crises. A change of direction rather than a change of rhythm. Japan is not in a hurry. And perhaps that is precisely why it is heading toward something the rest of the world is only beginning to sense.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Society 5.0 – Futuristic Sci-Fi in Japan Is Happening Now, Right Before Our Eyes. But Is It Already Too Late?

Stay Active and Thriving Even in Your 80s – The Japanese Phenomenon of Radio Taiso

'Cool Japan' Strategy: For a Government to Consistently Support Culture and to Account for Every Penny (Yen) for over 20 years

“If you don’t learn something new, you age faster than your body” – The Unbelievable Japanese Approach to Old Age

How did Japan, a country of the future, power, and innovation, become a land of the past, old age, and inertia?

Three Decades Without Growth—What Really Happened?

Three Decades Without Growth—What Really Happened?

Three Decades Without Growth—What Really Happened?

Three Decades Without Growth—What Really Happened?