A linguistic enigma

Not every mountain bears a name that survives thousands of years, becomes a national icon, and at the same time retains an aura of mystery. Even fewer are those whose names—merely two syllables long—become at once a national symbol, an object of religious worship, an emblem of the state, a motif in the logos of countless companies and corporations, and simultaneously a riddle for linguists. “Fuji”—now written with the characters 富士—is a word that cannot be clearly defined, either etymologically or semantically. Does it derive from the concept of immortality (不死, fu-shi), or perhaps signify a being with no equal (不二, fu-ni)? Might it be connected to the powerful Fujiwara clan? Or could its origin lie in the language of the indigenous peoples of the archipelago—Emishi or Ainu—where the echo of the word fuchi, the name of a fire goddess, may have gradually transformed into “Fuji”? In today’s article, we shall attempt to uncover some of the linguistic mysteries of Mount Fuji—from ancient phonemes to spiritual reinterpretations—in order to understand where this most powerful of Japanese names truly comes from.

Not every mountain bears a name that survives thousands of years, becomes a national icon, and at the same time retains an aura of mystery. Even fewer are those whose names—merely two syllables long—become at once a national symbol, an object of religious worship, an emblem of the state, a motif in the logos of countless companies and corporations, and simultaneously a riddle for linguists. “Fuji”—now written with the characters 富士—is a word that cannot be clearly defined, either etymologically or semantically. Does it derive from the concept of immortality (不死, fu-shi), or perhaps signify a being with no equal (不二, fu-ni)? Might it be connected to the powerful Fujiwara clan? Or could its origin lie in the language of the indigenous peoples of the archipelago—Emishi or Ainu—where the echo of the word fuchi, the name of a fire goddess, may have gradually transformed into “Fuji”? In today’s article, we shall attempt to uncover some of the linguistic mysteries of Mount Fuji—from ancient phonemes to spiritual reinterpretations—in order to understand where this most powerful of Japanese names truly comes from.

Our starting point is writing—or rather, its limitations. The combination of the characters 富 (“wealth, abundance”) and 士 (“warrior, man of rank”) is an example of ateji—a phonetic rendering of a native word using kanji selected not for their meaning but for their sound. In classical Chinese sources, the word 富士 does not exist as an independent lexical unit, which confirms that it is a secondary, Japanese creation. Yet already in the Heian and later Edo periods, these two characters became the inspiration for dozens of reinterpretations: Buddhist, Confucian, folkloric—each trying to frame the mountain’s name within systems of meaning drawn from mythology, religion, philosophy, entertainment, and politics. The kanji, although originally purely phonetic, gained new life as tools of spiritual and moral projection. It was not the kanji that conformed to the name—the name itself was rewritten by culture and its needs.

Our starting point is writing—or rather, its limitations. The combination of the characters 富 (“wealth, abundance”) and 士 (“warrior, man of rank”) is an example of ateji—a phonetic rendering of a native word using kanji selected not for their meaning but for their sound. In classical Chinese sources, the word 富士 does not exist as an independent lexical unit, which confirms that it is a secondary, Japanese creation. Yet already in the Heian and later Edo periods, these two characters became the inspiration for dozens of reinterpretations: Buddhist, Confucian, folkloric—each trying to frame the mountain’s name within systems of meaning drawn from mythology, religion, philosophy, entertainment, and politics. The kanji, although originally purely phonetic, gained new life as tools of spiritual and moral projection. It was not the kanji that conformed to the name—the name itself was rewritten by culture and its needs.

Fuji is thus not merely a geographic point, but a linguistic phenomenon—layered, dynamic, ambiguous. Its name has passed through the ages: from oral traditions among the peoples of pre-literate Japan, through the archaic Japanese of the Man’yōshū era, to the codified kanji script of the Heian and Kamakura periods. Each generation added its own meanings: Fuji as axis mundi, as mandala, as a symbol of immortality, purity, transcendence. In the Meiji era, the mountain appeared on banknotes; in the 20th century—on the logo of Japan Airlines; and today—in advertising brochures and collective consciousness. Yet the question remains the same: do we truly understand what “Fuji” means?

Fuji is thus not merely a geographic point, but a linguistic phenomenon—layered, dynamic, ambiguous. Its name has passed through the ages: from oral traditions among the peoples of pre-literate Japan, through the archaic Japanese of the Man’yōshū era, to the codified kanji script of the Heian and Kamakura periods. Each generation added its own meanings: Fuji as axis mundi, as mandala, as a symbol of immortality, purity, transcendence. In the Meiji era, the mountain appeared on banknotes; in the 20th century—on the logo of Japan Airlines; and today—in advertising brochures and collective consciousness. Yet the question remains the same: do we truly understand what “Fuji” means?

What is Mount Fuji?

Rising majestically to a height of 3,776.24 meters above sea level, Mount Fuji (富士山, Fujisan) is Japan’s highest peak and one of its most recognizable symbols. It is an almost perfectly symmetrical volcanic cone that dominates the landscape of central Honshū, straddling the border between Shizuoka and Yamanashi Prefectures. On a clear day, it can be seen from tens of kilometers away—from Tokyo, Yokohama, and even from outer space. Its presence on the 1000-yen banknote, in ukiyo-e painting, in calligraphy, religion, and poetry makes it something more than a geological formation—it is the axis of Japan’s cultural and spiritual landscape.

Rising majestically to a height of 3,776.24 meters above sea level, Mount Fuji (富士山, Fujisan) is Japan’s highest peak and one of its most recognizable symbols. It is an almost perfectly symmetrical volcanic cone that dominates the landscape of central Honshū, straddling the border between Shizuoka and Yamanashi Prefectures. On a clear day, it can be seen from tens of kilometers away—from Tokyo, Yokohama, and even from outer space. Its presence on the 1000-yen banknote, in ukiyo-e painting, in calligraphy, religion, and poetry makes it something more than a geological formation—it is the axis of Japan’s cultural and spiritual landscape.

Geologically speaking, Fuji is a young stratovolcano formed at the intersection of three tectonic plates: the Amurian, the Okhotsk, and the Philippine Sea plates. The mountain’s current form, referred to as “New Fuji,” began taking shape around 10,000 years ago, layering itself atop earlier volcanic formations—Komitake Fuji and Old Fuji. The last eruption occurred in 1707–1708, creating an additional crater—Hōei-zan—on the southeastern slope. Despite its long history of seismic activity, Fuji is currently dormant, though it is classified as an active volcano.

The area surrounding the mountain constitutes a unique microcosm of nature and culture. Dense forests, such as Aokigahara—the infamous “suicide forest” (The Aokigahara Suicide Forest: What Secrets Do the Silent Trees Guard?)—cover the northwestern slopes, concealing a wealth of flora and fauna as well as numerous legends. At lower elevations, pine, cypress, and chestnut trees dominate, while higher up, mosses, lichens, and small shrubs struggle against the harsh volcanic terrain. Fuji is not only a destination for naturalists and tourists, but also a site of religious pilgrimage—for followers of shintō and Buddhism, it represents a spiritual ascent toward enlightenment. Its slopes are crisscrossed by numerous trails, the oldest of which—like Yoshida or Murayama—pass through sacred sites, shrines, and stone statues, bearing witness to centuries of human presence in the mountain’s shadow.

The area surrounding the mountain constitutes a unique microcosm of nature and culture. Dense forests, such as Aokigahara—the infamous “suicide forest” (The Aokigahara Suicide Forest: What Secrets Do the Silent Trees Guard?)—cover the northwestern slopes, concealing a wealth of flora and fauna as well as numerous legends. At lower elevations, pine, cypress, and chestnut trees dominate, while higher up, mosses, lichens, and small shrubs struggle against the harsh volcanic terrain. Fuji is not only a destination for naturalists and tourists, but also a site of religious pilgrimage—for followers of shintō and Buddhism, it represents a spiritual ascent toward enlightenment. Its slopes are crisscrossed by numerous trails, the oldest of which—like Yoshida or Murayama—pass through sacred sites, shrines, and stone statues, bearing witness to centuries of human presence in the mountain’s shadow.

Fuji before written language

Before Japan encountered Chinese characters, before the first verses were written in man’yōgana, before ink began to flow across silk scrolls—there was the mountain. Visible from afar, smoking with fire, incomprehensible. And it had a name. Passed down from mouth to mouth like a spell, the sound “fuji” lived in human speech long before it was ever recorded. This name was not created at a scholar’s desk, but in the shadow of the forest, by the fire, in a gaze turned toward the cone rising above the clouds.

Before Japan encountered Chinese characters, before the first verses were written in man’yōgana, before ink began to flow across silk scrolls—there was the mountain. Visible from afar, smoking with fire, incomprehensible. And it had a name. Passed down from mouth to mouth like a spell, the sound “fuji” lived in human speech long before it was ever recorded. This name was not created at a scholar’s desk, but in the shadow of the forest, by the fire, in a gaze turned toward the cone rising above the clouds.

Before the era of writing, the Japanese language was entirely oral—and not uniform, but woven from dialects, vernaculars, rituals, and songs. Mount Fuji appears for the first time in written texts in the 8th century, in the collections Fudoki and Nihon Shoki, but its name was certainly older than these compilations. Already in the Taketori monogatari (10th century), there appears a wordplay linking it with “immortality” (fushi, 不死), suggesting that the sound “fuji” was already well established by then, and that its meaning was only beginning to be overwritten.

We do not know exactly how the word was pronounced in pre-literate Japan, but research into ancient phonologies and comparisons with other archipelagic languages—including Ainu and Ryūkyū—suggest that the mountain’s name may have had a root present across various linguistic strata. Some hypotheses propose that it may have sounded similar to “fuchi,” “fusi,” or “pusi”—phonetic forms common in both Old Japanese and other indigenous languages such as Emishi (more on them here: Emishi – The Forgotten People of the Japanese Islands Before Yamato and the Ainu). Pre-literate Japan was, after all, a mosaic of peoples and languages—and each of them could have interpreted and named this mountain through the prism of their own beliefs, emotions, and relationship with the landscape.

We do not know exactly how the word was pronounced in pre-literate Japan, but research into ancient phonologies and comparisons with other archipelagic languages—including Ainu and Ryūkyū—suggest that the mountain’s name may have had a root present across various linguistic strata. Some hypotheses propose that it may have sounded similar to “fuchi,” “fusi,” or “pusi”—phonetic forms common in both Old Japanese and other indigenous languages such as Emishi (more on them here: Emishi – The Forgotten People of the Japanese Islands Before Yamato and the Ainu). Pre-literate Japan was, after all, a mosaic of peoples and languages—and each of them could have interpreted and named this mountain through the prism of their own beliefs, emotions, and relationship with the landscape.

The kanji 富士 as ateji – phonetic or semantic writing?

When China began to exert cultural influence over Japan, and Chinese characters were adopted to transcribe the Japanese language, a fundamental problem emerged: how to write words that had an established pronunciation but no assigned character? In such cases, the solution was ateji—characters used not for their meaning but for their sound. This is exactly how Fuji came to be written: 富士, where fu and ji correspond to the pronunciation, not the original meaning of the word.

When China began to exert cultural influence over Japan, and Chinese characters were adopted to transcribe the Japanese language, a fundamental problem emerged: how to write words that had an established pronunciation but no assigned character? In such cases, the solution was ateji—characters used not for their meaning but for their sound. This is exactly how Fuji came to be written: 富士, where fu and ji correspond to the pronunciation, not the original meaning of the word.

The first character, 富 (fu), means “wealth” or “abundance.” The second, 士 (shi or ji), refers to a “man of rank,” often interpreted as “warrior” or “scholar.” Taken together, 富士 could be read as “rich warrior” or “man of abundance”—but there is no evidence to suggest that this is how the name was originally understood. It was not a description of the mountain, but rather a phonetic match using available characters with the desired sound. Semantics were assigned later.

Over time, however, these characters—originally purely phonetic—began to be reinterpreted anew: poetically, spiritually, symbolically. In the Edo period, interpretations of the character pair “富士” appeared, suggesting that Fuji meant “wealth of virtues,” “mountain of abundance and chivalry,” or even “abundance of the samurai spirit.” This phenomenon of semantic overwriting of ateji—creating secondary, often romantic explanations for characters that were originally chosen solely for their sound—reveals much. In this sense, the spelling 富士 tells us nothing about the origin of the name, but a great deal about how the Japanese wished to understand it.

Over time, however, these characters—originally purely phonetic—began to be reinterpreted anew: poetically, spiritually, symbolically. In the Edo period, interpretations of the character pair “富士” appeared, suggesting that Fuji meant “wealth of virtues,” “mountain of abundance and chivalry,” or even “abundance of the samurai spirit.” This phenomenon of semantic overwriting of ateji—creating secondary, often romantic explanations for characters that were originally chosen solely for their sound—reveals much. In this sense, the spelling 富士 tells us nothing about the origin of the name, but a great deal about how the Japanese wished to understand it.

The kanji script here functions as a cultural mirror: it reflects not only language, but also aspirations, dreams, and ideals. In a world where every word can become a poem, even a phonetic rendering does not remain free of meaning for long. Fuji, though it may have originally sounded like the echo of fire, smoke, and stone, came to be read as an allegory of abundance, chivalry, immortality—exactly what the Japanese wished to see in their sacred mountain.

Folk etymologies and classical reinterpretations

Once the phonetic Fuji was absorbed into the kanji writing system, it immediately began to undergo reinterpretation—not linguistic, but spiritual, philosophical, and poetic. Japan has always had a tendency to attribute sensory, ethical, and spiritual meanings to things that, on the surface, are merely names. What began as a purely sonic name for a majestic mountain eventually became enmeshed in a network of possible etymologies—each revealing something different about the collective imagination of the Heian, Kamakura, or Edo periods.

Once the phonetic Fuji was absorbed into the kanji writing system, it immediately began to undergo reinterpretation—not linguistic, but spiritual, philosophical, and poetic. Japan has always had a tendency to attribute sensory, ethical, and spiritual meanings to things that, on the surface, are merely names. What began as a purely sonic name for a majestic mountain eventually became enmeshed in a network of possible etymologies—each revealing something different about the collective imagination of the Heian, Kamakura, or Edo periods.

The first often-cited etymology is 不死 (fu-shi)—“immortality.” This compound, in which 不 (fu) denotes negation and 死 (shi) means death, was especially potent in a literary context. It appears as early as the 10th-century tale Taketori monogatari, where the emperor, having received an elixir of immortality from Princess Kaguya, decides to burn it atop a mountain, which thereafter bears the name Fuji. This story not only gives the mountain a name associated with immortality but also binds it to sacrifice, melancholy, and the metaphysical choice between life and transcendence.

The second popular etymology is 不二 (fu-ni)—“not two” or “the one and only.” This compound gained favor among Confucian and Buddhist scholars of the Heian period and later eras. It was interpreted as a sign of spiritual singularity—something incomparable, unique, one of a kind. In Mahayana Buddhism, funi (不二) signifies the unity of opposites—the absence of dualism between conventional truth and ultimate truth. Identifying Mount Fuji with this idea elevates it beyond the landscape, transforming it into a symbol of enlightenment, of spiritual oneness, as if the mountain itself were a mandala rising from the earth. For pilgrims and poets alike, it was not merely the highest peak of Japan but the summit of spiritual unity.

The second popular etymology is 不二 (fu-ni)—“not two” or “the one and only.” This compound gained favor among Confucian and Buddhist scholars of the Heian period and later eras. It was interpreted as a sign of spiritual singularity—something incomparable, unique, one of a kind. In Mahayana Buddhism, funi (不二) signifies the unity of opposites—the absence of dualism between conventional truth and ultimate truth. Identifying Mount Fuji with this idea elevates it beyond the landscape, transforming it into a symbol of enlightenment, of spiritual oneness, as if the mountain itself were a mandala rising from the earth. For pilgrims and poets alike, it was not merely the highest peak of Japan but the summit of spiritual unity.

The third frequently referenced etymology is 不尽 (fu-jin)—“inexhaustible,” “without end.” This compound pairs the negation 不 with the verb 尽 (tsukiru), meaning “to be exhausted,” “to end,” “to reach a limit.” It can be interpreted as a reference to endless abundance—Fuji as the mountain that never stops giving: water, views, inspiration, spiritual presence. In a religious context, it may symbolize hōmatsu no michi (法末の道), the “path without end” one walks toward enlightenment. In an aesthetic context, it may signify beauty that does not deplete, that endures despite the changing seasons and times.

The third frequently referenced etymology is 不尽 (fu-jin)—“inexhaustible,” “without end.” This compound pairs the negation 不 with the verb 尽 (tsukiru), meaning “to be exhausted,” “to end,” “to reach a limit.” It can be interpreted as a reference to endless abundance—Fuji as the mountain that never stops giving: water, views, inspiration, spiritual presence. In a religious context, it may symbolize hōmatsu no michi (法末の道), the “path without end” one walks toward enlightenment. In an aesthetic context, it may signify beauty that does not deplete, that endures despite the changing seasons and times.

From a linguistic standpoint, all of these etymologies are secondary—arising from the reinterpretation of the already existing word Fuji through associations with other similarly sounding words or characters. Japanese literary and philosophical tradition was fond of such practices. Their purpose was not to determine the true origin of the name but to endow it with cultural depth. Scholars of the Edo period—such as Motoori Norinaga or Hirata Atsutane—did not have access to modern historical linguistics, but they possessed a profound sensitivity to sound, meaning, and the symbolism of writing. For them, kanji was not merely a script—it was a tool for discovering the essence of things. In those days, the study of language was not yet a science—it was closer to poetry.

From a linguistic standpoint, all of these etymologies are secondary—arising from the reinterpretation of the already existing word Fuji through associations with other similarly sounding words or characters. Japanese literary and philosophical tradition was fond of such practices. Their purpose was not to determine the true origin of the name but to endow it with cultural depth. Scholars of the Edo period—such as Motoori Norinaga or Hirata Atsutane—did not have access to modern historical linguistics, but they possessed a profound sensitivity to sound, meaning, and the symbolism of writing. For them, kanji was not merely a script—it was a tool for discovering the essence of things. In those days, the study of language was not yet a science—it was closer to poetry.

All these etymologies share one thing in common: each reinforces the spiritual image of Mount Fuji. In them, the mountain is not a physical object, but a spiritual center—the axis mundi of Japan. Immortal, singular, inexhaustible—it becomes what the Japanese wished it to be. And at the same time, each of these etymologies, though linguistically tenuous, carries a grain of truth—for Mount Fuji truly has no equal, never ceases to inspire, and still stands, unshaken, despite the passing of millennia.

Traces of the Ainu Language – Fuchi, the Goddess of Fire

Among the most intriguing and at the same time controversial hypotheses regarding the name of Mount Fuji is the one that leads us far beyond Japanese written tradition, into the oral heritage of one of the ancient peoples of the archipelago—the Ainu. According to this theory, the name Fuji may have its roots in the Ainu word fuchi (also written huchi), which means fire, as well as in the name of the fire goddess—Kamuy Fuchi, a central figure in Ainu mythology.

Among the most intriguing and at the same time controversial hypotheses regarding the name of Mount Fuji is the one that leads us far beyond Japanese written tradition, into the oral heritage of one of the ancient peoples of the archipelago—the Ainu. According to this theory, the name Fuji may have its roots in the Ainu word fuchi (also written huchi), which means fire, as well as in the name of the fire goddess—Kamuy Fuchi, a central figure in Ainu mythology.

Kamuy Fuchi (or Kamui-huci) is not merely a deity of the element—she is the guardian of the hearth, the intermediary between the world of humans and spirits, a goddess present in every Ainu dwelling, at the very heart of daily life. The hearth over which she watched was regarded as a sacred space through which offerings were made and prayers transmitted to other gods. Significantly, Kamuy Fuchi was never depicted visually—her presence was expressed solely through word and ritual, drawing her close to the universal archetypes of fire as a medium of divinity.

It is precisely this symbolism of fire—its verticality, dynamism, heat, and power of transformation—that forms the foundation of the hypothesis that the volcanic cone of Mount Fuji may have been perceived by ancient peoples as the earthly form of a fire deity. One need not stretch the imagination far to see in Fuji a flame sealed in stone—a fire frozen, but not dead. A volcano as a slumbering goddess. In this sense, even if the phonetic boundary between fuchi and fuji exists, it is separated only by half a step of imagination.

It is precisely this symbolism of fire—its verticality, dynamism, heat, and power of transformation—that forms the foundation of the hypothesis that the volcanic cone of Mount Fuji may have been perceived by ancient peoples as the earthly form of a fire deity. One need not stretch the imagination far to see in Fuji a flame sealed in stone—a fire frozen, but not dead. A volcano as a slumbering goddess. In this sense, even if the phonetic boundary between fuchi and fuji exists, it is separated only by half a step of imagination.

Yet here the problem arises: did the Ainu truly inhabit the lands at the foot of Mount Fuji? Most archaeological and ethnohistorical studies indicate that the Ainu peoples settled mainly on Hokkaidō, Sakhalin, and the eastern part of Honshū—but not as far south as the present-day prefectures of Yamanashi or Shizuoka. These regions may have been inhabited by the Emishi—a people considered culturally and ethnically distinct from the Yamato (read more about their wars with the Yamato here: Forgotten Wars of Ancient Japan – The Emishi Versus Yamato), possibly related to the Ainu but not identical. Thus, even if the word fuchi existed in the languages of the northern peoples of the archipelago, its migration southward would have had to proceed through channels of trade contact or long processes of linguistic assimilation.

This hypothesis was popularized by, among others, the British missionary Bob Chiggleson, who claimed that the name Fuji derives directly from the name Kamuy Fuchi. However, this theory was rejected by the Japanese linguist Kyōsuke Kindaichi (金田一 京助)—a renowned scholar of the Ainu language. According to him, the phonetic shift from fuchi to fuji is phonologically improbable in light of known rules governing the evolution of the Japanese language. Furthermore, he noted that in the Ainu language, the word ape (アペ) refers to fire as a physical phenomenon, while huchi is closer in meaning to “old woman,” making the goddess’s significance not so much “fiery” as “matron of the hearth.” In fact, the full name of the goddess—Ape Huchi Kamuy—can be translated as “deity of the old woman of fire.”

This hypothesis was popularized by, among others, the British missionary Bob Chiggleson, who claimed that the name Fuji derives directly from the name Kamuy Fuchi. However, this theory was rejected by the Japanese linguist Kyōsuke Kindaichi (金田一 京助)—a renowned scholar of the Ainu language. According to him, the phonetic shift from fuchi to fuji is phonologically improbable in light of known rules governing the evolution of the Japanese language. Furthermore, he noted that in the Ainu language, the word ape (アペ) refers to fire as a physical phenomenon, while huchi is closer in meaning to “old woman,” making the goddess’s significance not so much “fiery” as “matron of the hearth.” In fact, the full name of the goddess—Ape Huchi Kamuy—can be translated as “deity of the old woman of fire.”

Does this mean the hypothesis is incorrect? Most likely, yes—but that does not prevent it from being simultaneously inspiring. Although linguistically weak, it possesses immense expressive power in cultural and symbolic terms. The combination of a female fire deity, her centrality to the home, and her sacredness with the image of a majestic volcano is an archetype deeply rooted not only in Ainu culture but in the human imagination as a whole. In this light, Fuji as a materialized Kamuy Fuchi—a mountain as the living memory of the divine woman of fire—functions not as an etymological hypothesis, but as a mythological truth.

Does this mean the hypothesis is incorrect? Most likely, yes—but that does not prevent it from being simultaneously inspiring. Although linguistically weak, it possesses immense expressive power in cultural and symbolic terms. The combination of a female fire deity, her centrality to the home, and her sacredness with the image of a majestic volcano is an archetype deeply rooted not only in Ainu culture but in the human imagination as a whole. In this light, Fuji as a materialized Kamuy Fuchi—a mountain as the living memory of the divine woman of fire—functions not as an etymological hypothesis, but as a mythological truth.

Many scholars of Japanese culture point out that even if this theory does not conform to historical and linguistic logic, it reveals something equally important: the deep intuition of the human spirit, which always connects landscape with meaning, and language with emotion. It is thus possible that fuchi and fuji are not etymologically related but are close on the level of what Carl Gustav Jung would call a primal symbol—a fire that does not go out.

Other Diverse Hypotheses

Although the most commonly cited etymologies of the name Fuji refer to negation and metaphysics—“immortality,” “without equal,” “inexhaustibility”—in the shadow of these interpretations there exists a range of lesser-known but intriguing hypotheses that link language with nature, vegetation, and the human sense of observation. These are folk, poetic, sometimes slightly esoteric theories, yet deeply rooted in the Japanese tradition of interpreting the world through signs, sounds, and images. Even if they tell us little about the actual origin of the name Fuji, they certainly tell us a great deal about those in whose culture these hypotheses arose.

“A mountain like a head of rice” – the hypothesis of Hirata Atsutane

“A mountain like a head of rice” – the hypothesis of Hirata Atsutane

One of the most original interpretations was proposed by Hirata Atsutane (平田篤胤, 1776–1843)—a national scholar and religious traditionalist (kokugakusha) of the Edo period, known for his efforts to restore the significance of native Japanese spirituality (shintō) and pre-Chinese language. Atsutane postulated that the name “Fuji” might not derive from abstract metaphysical concepts, but from a visual metaphor—he compared the silhouette of the mountain to a head of rice, or 穂 (ho).

In his interpretation, Fuji would be a phonetically distorted transformation of an Old Japanese expression meaning “something that stands straight and noble like a mature head of rice”—a symbol of abundance, order, and harmony with nature. In Japanese imagination, the rice head (穂) is not only part of a plant but a metaphor for maturity, fullness, and the connection between heaven and earth. Although linguistically the hypothesis is tenuous, it reflects the Edo-era tendency to create “aesthetic-symbolic etymologies,” in which the goal was not historical accuracy but harmony with an idea.

藤 as “fuji” – the wisteria that climbs toward the sky

藤 as “fuji” – the wisteria that climbs toward the sky

Another possibility, occasionally discussed and surprisingly fitting from a cultural standpoint, is the association of Mount Fuji’s name with the kanji 藤, also read fuji, which means “wisteria”—a climbing plant with drooping clusters of violet blossoms, immensely popular in Japanese aesthetics, especially during the Heian period and later in the Edo era. Wisteria is a recurring motif in poetry (waka, haiku), painting, kimono patterns, family crests (kamon)—a symbol of delicacy, elegance, dignity, and also strength.

Although there is no evidence that this particular character was originally used to write the mountain’s name, its phonetic identity and deep roots in poetic and visual language lead many scholars of Japanese art to see a kinship here—if not a historical one, then at least a symbolic one. The wisteria climbs upward—spiraling, subtly, with grace. Is it not a botanical counterpart of our volcano? Fuji as a mountain not of fire, but of growth and restrained power—a powerful and inspiring image.

Although there is no evidence that this particular character was originally used to write the mountain’s name, its phonetic identity and deep roots in poetic and visual language lead many scholars of Japanese art to see a kinship here—if not a historical one, then at least a symbolic one. The wisteria climbs upward—spiraling, subtly, with grace. Is it not a botanical counterpart of our volcano? Fuji as a mountain not of fire, but of growth and restrained power—a powerful and inspiring image.

Interestingly, during the Heian period there existed influential clans bearing the name Fujiwara (藤原), which also uses this character. Although there is no direct link between the mountain’s name and the clan’s surname, the fact that both forms are homophones contributed to additional cultural connotations in the centuries that followed.

A rainbow etymology – the forgotten word “fuji” as “niji”

There are archaic phonetic variants in which the word for “rainbow” (now written 虹 – niji) had an alternative form: fuji. In the Japanese language before modern readings were standardized, many words existed in regional or ritual variants—spelling was not fixed, and pronunciation was variable. If such a form truly existed, it might have been transferred to the mountain’s name—as a metaphor for an arc across the sky, bridging worlds, heralding hope, and appearing through the interplay of rain and light—just like Fuji rising above the mist.

There are archaic phonetic variants in which the word for “rainbow” (now written 虹 – niji) had an alternative form: fuji. In the Japanese language before modern readings were standardized, many words existed in regional or ritual variants—spelling was not fixed, and pronunciation was variable. If such a form truly existed, it might have been transferred to the mountain’s name—as a metaphor for an arc across the sky, bridging worlds, heralding hope, and appearing through the interplay of rain and light—just like Fuji rising above the mist.

Of course, from the perspective of historical linguistics, this etymology is highly speculative, but as an example of ancient poetic thought, it is compelling. In Japanese culture, the rainbow was not merely a natural phenomenon, but a bridge of spirits, a harbinger of change, a gate. Mount Fuji as a rainbow axis between worlds? Perhaps.

Toponymic arguments – Fuji beyond Fuji-san

An additional clue in our search may come from the analysis of toponyms—that is, place names containing the element “fuji.” In Japan, there are numerous geographic names that include this word—Fujiyoshida, Fujinomiya, Fujikawa, Fujioka—as well as surnames and family crests (Fujiwara, Fujimoto, Fujisaki, etc.).

An additional clue in our search may come from the analysis of toponyms—that is, place names containing the element “fuji.” In Japan, there are numerous geographic names that include this word—Fujiyoshida, Fujinomiya, Fujikawa, Fujioka—as well as surnames and family crests (Fujiwara, Fujimoto, Fujisaki, etc.).

It is worth noting, however, that in most cases, it was Mount Fuji that served as the point of origin—these towns and surnames were derived from it, not the other way around. Moreover, toponymic research (e.g., conducted by Japanese dialectologists at Tōhoku University) suggests that the sound “fuji” in locations far from the mountain more often refers to “wisteria” (藤) than to the “volcanic mountain.” This indicates that the fuji element was highly productive both phonetically and semantically—it could mean different things in different contexts, further obscuring the original meaning of the mountain’s name.

We do not know whether Mount Fuji received its name from a head of rice, a plant, or perhaps a weather phenomenon—but we do know that all these associations lived on in language, in imagination, and in metaphor. Japan is a country where names are rarely purely functional. Fuji is not just a place name, but a word that, over the centuries, has absorbed meaning like the mist that clings to its slopes—quiet, elusive, yet dense with symbolism.

Fuji as an archetype of Japanese culture

After all the phonetic and etymological analyses, after tracing the footsteps of the Ainu and Confucian reinterpretations, we must finally ask: why this mountain in particular? Among so many peaks in Japan—taller, wilder, more inaccessible—it was Fuji that became sacred. Why is it this name, out of the thousands of toponyms on the archipelago, that has become so enshrouded in meaning, myth, and the aesthetics of entire eras?

After all the phonetic and etymological analyses, after tracing the footsteps of the Ainu and Confucian reinterpretations, we must finally ask: why this mountain in particular? Among so many peaks in Japan—taller, wilder, more inaccessible—it was Fuji that became sacred. Why is it this name, out of the thousands of toponyms on the archipelago, that has become so enshrouded in meaning, myth, and the aesthetics of entire eras?

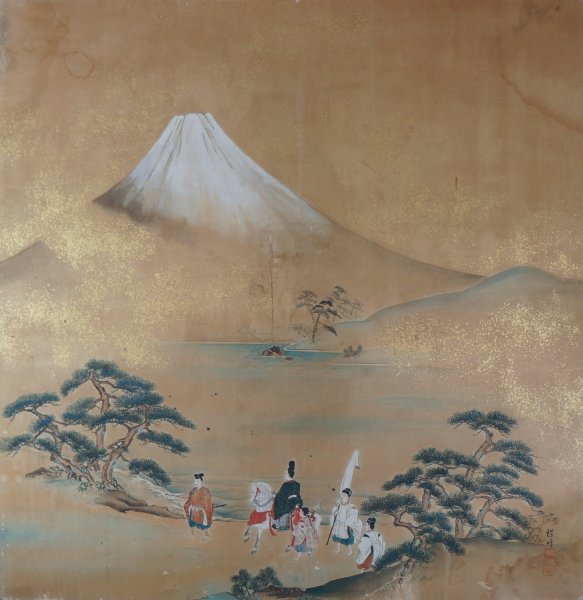

Perhaps the answer lies not in language but in the archetype. The conical silhouette of Fuji—perfect, solitary, almost geometric—fits universal human ideas of the mountain as axis of the world, point of contact between heaven and earth, matter and spirit. In Japan, it was Fuji that came to be seen as the axis mundi—the central point of the landscape, but also of the spiritual cosmos. In shintō tradition, it served as a yorishiro, a place capable of receiving the presence of kami. In Buddhism, especially in esoteric forms (such as shingon), the mountain took on the dimension of a mandala—a spiritual map of the universe through which the pilgrim journeys toward enlightenment. Fuji not only connected heaven and earth—it became the path itself, a vertical route of transformation.

Perhaps the answer lies not in language but in the archetype. The conical silhouette of Fuji—perfect, solitary, almost geometric—fits universal human ideas of the mountain as axis of the world, point of contact between heaven and earth, matter and spirit. In Japan, it was Fuji that came to be seen as the axis mundi—the central point of the landscape, but also of the spiritual cosmos. In shintō tradition, it served as a yorishiro, a place capable of receiving the presence of kami. In Buddhism, especially in esoteric forms (such as shingon), the mountain took on the dimension of a mandala—a spiritual map of the universe through which the pilgrim journeys toward enlightenment. Fuji not only connected heaven and earth—it became the path itself, a vertical route of transformation.

Pilgrimages to Fuji were practiced as early as the classical and medieval periods, and in the Edo era this movement became almost mass-scale. Fuji-kō associations were formed, whose members pooled resources to undertake the journey to the summit together. At the heart of these journeys lay not just faith—but also a profound need for spiritual connection with something greater than the individual. Fuji became a mirror—reflecting both the divine and the human.

Pilgrimages to Fuji were practiced as early as the classical and medieval periods, and in the Edo era this movement became almost mass-scale. Fuji-kō associations were formed, whose members pooled resources to undertake the journey to the summit together. At the heart of these journeys lay not just faith—but also a profound need for spiritual connection with something greater than the individual. Fuji became a mirror—reflecting both the divine and the human.

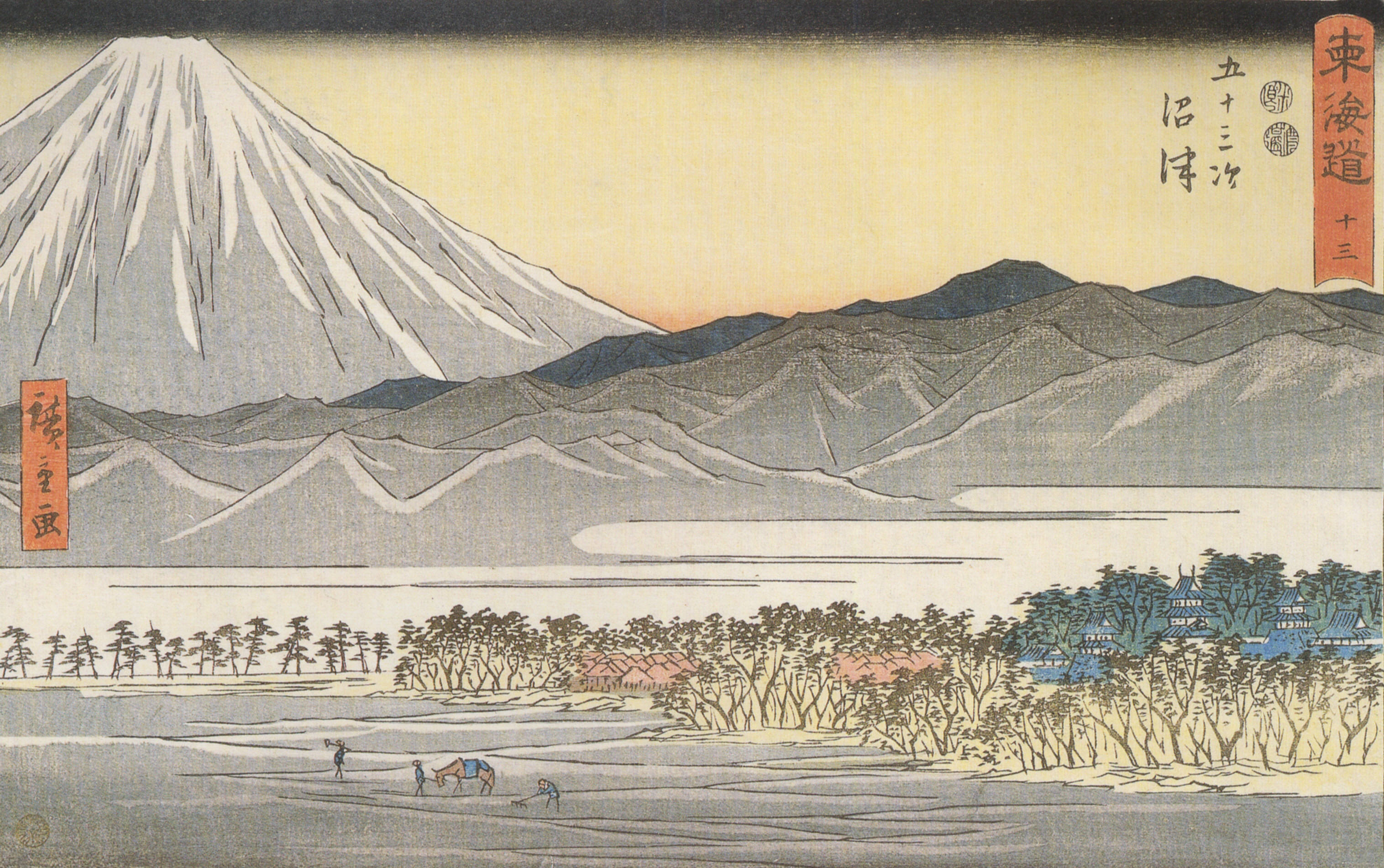

This same motif appears in art and literature. In the Man’yōshū anthology, Fuji appears as a proud, solitary, eternally beautiful mountain—and at the same time fearsome, carrying within it the power of fire. In Taketori monogatari, Fuji is the place where the emperor burns the elixir of immortality, making it a space of final parting and transcendence. Hokusai, in creating his series Fugaku Sanjūrokkei (“Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji”), depicted it at different times of day, in various weather conditions and moods—but always as the fixed point in a changing world. Hiroshige did the same in his own version of the cycle. For both artists, Fuji was what the key word is to the poet: an eternal metaphor.

This same motif appears in art and literature. In the Man’yōshū anthology, Fuji appears as a proud, solitary, eternally beautiful mountain—and at the same time fearsome, carrying within it the power of fire. In Taketori monogatari, Fuji is the place where the emperor burns the elixir of immortality, making it a space of final parting and transcendence. Hokusai, in creating his series Fugaku Sanjūrokkei (“Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji”), depicted it at different times of day, in various weather conditions and moods—but always as the fixed point in a changing world. Hiroshige did the same in his own version of the cycle. For both artists, Fuji was what the key word is to the poet: an eternal metaphor.

In modern times as well, Mount Fuji is not merely a peak—it is an icon. Its shape appears on the 1000 yen banknote, in company logos, on book covers, in pop culture, in the dreams of tourists and the meditations of artists. Even if one does not know Japanese geography, one knows Fuji—as the symbol of the entire country. In the shadow of this mountain, the history of Japan has been written—its religions, aesthetics, and national anxieties.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

The Kanji “Path” (道, dō) – On the Road to Mastery, the Message is One: Patience

Kanji 妖怪: Yōkai Are Not Demons of Legend, But a State Where a Fragile Reality Becomes Uncertain

Urami: the Silenced Wrong, All-Encompassing Grief, Fury — What Emotions Are Encoded in the Character “怨”

The Ainu Uprising on Hokkaidō 1669 – Shakushain and 19 Tribes Against the Shogun

Indigenous Inhabitants of Hokkaidō: The Ainu – Resourceful and Entrepreneurial Rulers of Ice and Waves in the Sea of Okhotsk

“A mountain like a head of rice” – the hypothesis of Hirata Atsutane

“A mountain like a head of rice” – the hypothesis of Hirata Atsutane 藤 as “fuji” – the wisteria that climbs toward the sky

藤 as “fuji” – the wisteria that climbs toward the sky

“A mountain like a head of rice” – the hypothesis of Hirata Atsutane

“A mountain like a head of rice” – the hypothesis of Hirata Atsutane 藤 as “fuji” – the wisteria that climbs toward the sky

藤 as “fuji” – the wisteria that climbs toward the sky