Redaktor naczelny

Pasjonat kultury azjatyckiej z głębokim uznaniem dla różnorodnych filozofii świata. Z wykształcenia psycholog i filolog - koreanista. W sercu programista (gł. na Androida) i gorący entuzjasta technologii. W chwilach spokoju hołduje zdyscyplinowanemu stylowi życia, głęboko wierząc, że wytrwałość, nieustający rozwój osobisty i oddanie się swoim pasjom to mądra droga życia.

Osobiste motto:

"Najpotężniejszą siłą we wszechświecie jest procent składany." - Albert Einstein (prawdopodobnie)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Now We Are in the Reiwa Era Since 2019. What Does This Precisely Mean?

Breaking Tradition in Naming

Breaking Tradition in Naming

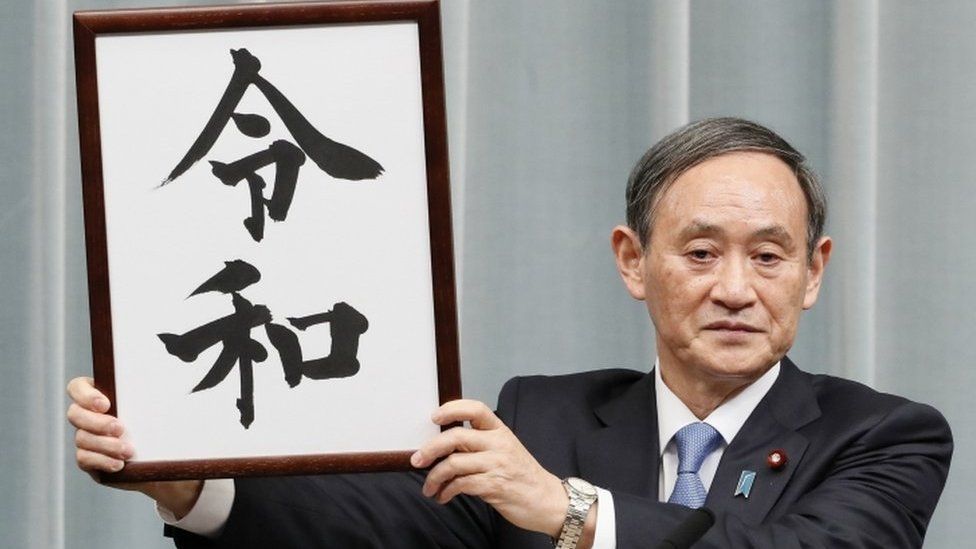

The Reiwa era, beginning on May 1, 2019, marks a significant moment in the history of naming Japanese epochs. For the first time, an era name was inspired by Japanese rather than Chinese classical literature. Characterized by the kanji "令" (rei) and "和" (wa), Reiwa draws from a poem about blooming plums in the "Man’yōshū," the oldest existing collection of Japanese poetry.

While Reiwa in a literary context signifies "fortunate" or "auspicious" harmony, some note alternate connotations of the character "令," which can mean "order" or "command." Similarly, the character "和" used in "Yamato," an old name for Japan associated with the country's military aspect, brings different connotations.

Symbolizing a New Beginning

The naming of the new era carries great significance. Like gengo throughout Japan's modern history, Reiwa is meant to symbolize a new start and direction for Japan. The Prime Minister of Japan indicated that the new era should reflect pride in the country's history and traditions along with hope for the future.

Like previous imperial eras, Reiwa will over time become closely associated with significant domestic and national events. The Meiji era (1868-1912) is remembered for modernization, the Showa era (1926-1989) for rapid economic growth but also Japanese militarism and World War II. The Heisei era (1989-2019) brought the end of the economic bubble and strained relations with China, as well as being marked by the Tokyo subway terrorist attack, the Kobe earthquake, and the Fukushima disaster in 2011.

Controversies

Although many enthusiastically embraced the new era's name, some criticize it as a return to pre-war monarchism. There is also a debate over the necessity of the era system in modern society. Hiroshi Kozen, an emeritus professor of Chinese literature at Kyoto University, notes that the era system should reflect people's desires, and a discussion about its need is essential. No such discussion has taken place to date.

The Reiwa era begins as Japan grapples with numerous challenges, such as an aging population, the need for economic reform, and adaptation to a rapidly changing technological world. In this context, the name "Reiwa," evoking nostalgia for tradition and harmony, may be seen as an incomplete representation of the reality in which modern Japan must find a balance between respect for the past and a dynamic, unpredictable future direction.

□ Reiwa Period (令和時代, Reiwa jidai)

Years: From 2019 CE to the present

The Reiwa period began with the ascension to the throne of Emperor Naruhito in 2019. It is a time for reflecting on the past and looking towards the future, with hopes for peace and progress.

Contemporary Japan faces many challenges, including further aging of the population, climate change, and the need to adapt to a rapidly changing global environment.

In the Reiwa period, Japan is focusing on technological innovations and sustainable development, striving for harmonious coexistence with nature and the rest of the world. This is a time when Japan continues to play a significant role internationally, both economically and culturally.

□ Heisei Period (平成時代, Heisei jidai)

Years: Approximately 1989 – 2019 CE

The Heisei period began following the death of Emperor Hirohito. It was a time of facing new economic challenges, including stagnation and the speculative bubble of the 90s.

The Heisei era was also a time of tremendous technological progress and further globalization. Japan strengthened its position as a leader in technological innovation.

This period also witnessed significant social changes, including an aging population and demographic shifts. Key events included natural disasters such as the Kobe earthquake in 1995 and the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami in 2011.

□ Showa Period (昭和時代, Showa jidai)

Years: Approximately 1926 – 1989 CE

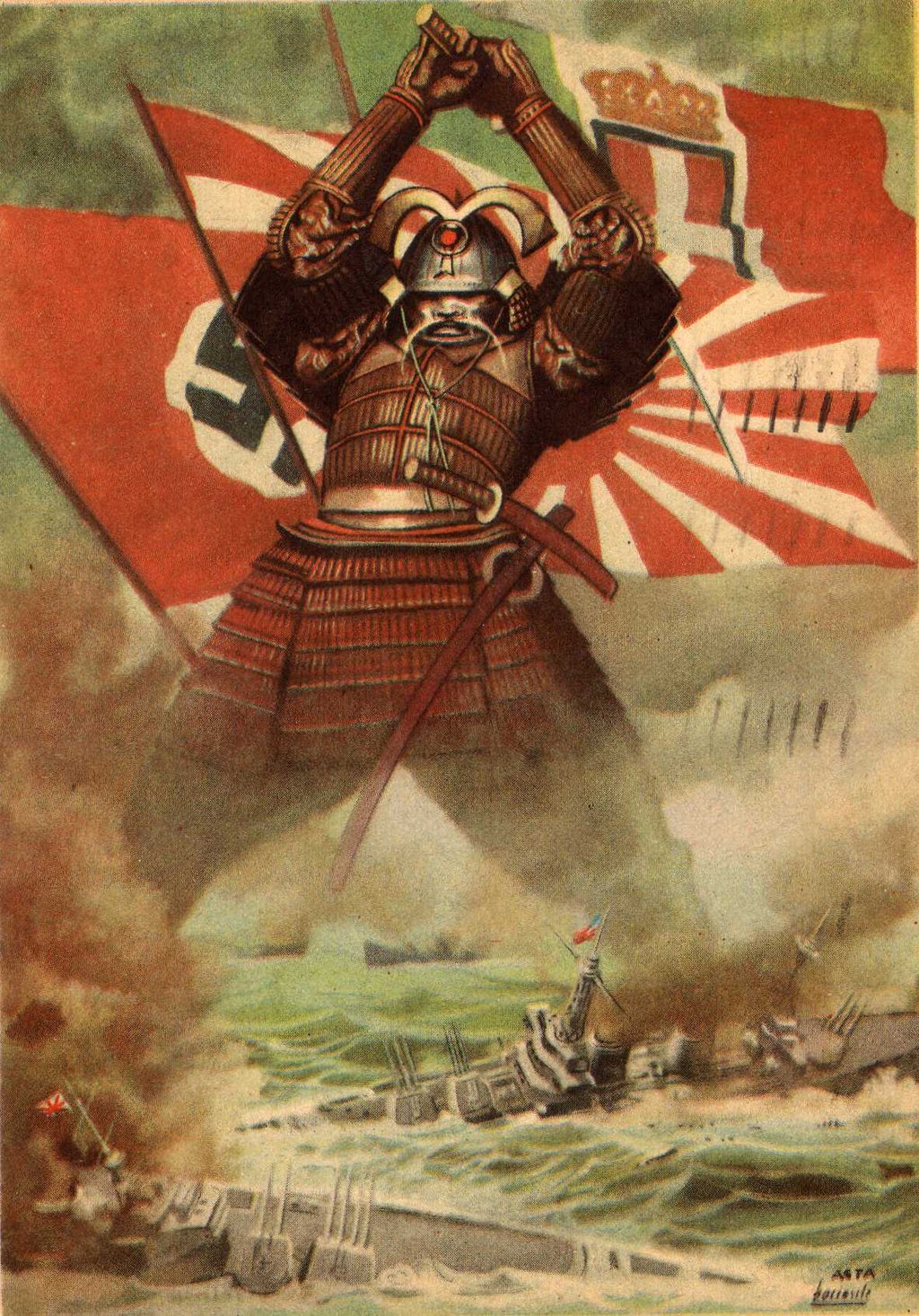

The Showa period encompasses both World War II and the post-war economic boom. It was a period of dramatic changes, from totalitarian expansion before and during the war to peaceful reconstruction and economic growth afterward.

After the war, Japan experienced significant economic growth, becoming one of the world's largest economies. The development of technology, industry, and exports were key elements of this success.

The Showa period was also a time of significant social and political changes, including the introduction of a new pacifist constitution and the development of democracy.

□ Taisho Period (大正時代, Taisho jidai)

Years: Approximately 1912 – 1926 CE

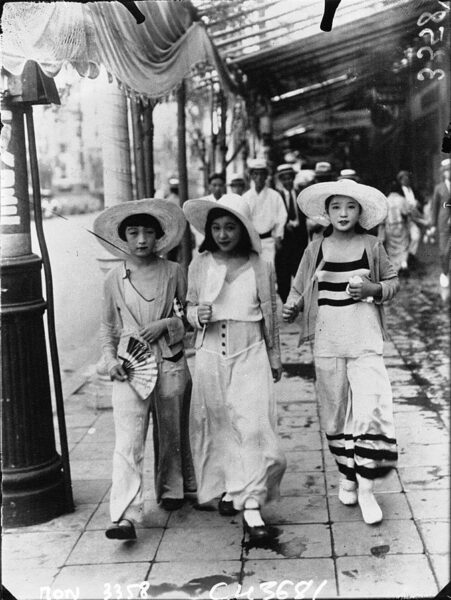

The Taisho period was a time when democratization and political liberalization progressed, partly influenced by the successes of the Meiji era and social changes following World War I.

This was also a period of cultural and artistic development, with visible Western influences in literature, painting, and theater. It was an era of increased social and cultural awareness.

The Taisho period also brought challenges such as economic disaster and rising political tensions, which eventually led to an increase in military and authoritarian approaches in the following era.

□ Meiji Period (明治時代, Meiji jidai)

Years: Approximately 1868 – 1912 CE

The Meiji period begins with the Meiji Restoration, which marked the return of power to the emperor and the end of the Tokugawa shogunate. It was a time of intense modernization and Western industrialization.

During the Meiji period, Japan underwent profound social and political changes, introducing a constitution and a parliamentary system of government. Reforms also included education, law, and the military.

The Meiji era was also a period of opening Japan to the world and active participation in international political and trade relations, significantly contributing to the rise of its status as a modern state.

□ Edo Period (Tokugawa) (江戸時代, Edo jidai)

Years: Approximately 1603 – 1868 CE

The Edo period is known for its long-lasting peace and stability, achieved through strict social and political control by the Tokugawa shogunate. It was a time of isolation of Japan from the rest of the world (sakoku policy), limiting external influences and foreign trade.

Despite the isolation, the Edo period was also a time of intense cultural development, especially among the merchant class. This was when art forms such as ukiyo-e (woodblock prints), kabuki literature, and bunraku (puppet theatre) emerged.

The Edo period saw an increase in population and urbanization, as well as the development of education and a refined urban culture. Despite its stability, this period ended with significant political and social changes, leading to the Meiji Restoration and the end of the shogunate era.

□ Azuchi-Momoyama Period (安土桃山時代, Azuchi-Momoyama jidai)

Years: Approximately 1568 – 1600 CE

This was a period of unification of Japan under the leadership of Oda Nobunaga and his successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Their actions led to the end of prolonged civil wars and the establishment of a stronger central authority.

The Azuchi-Momoyama period saw the development of a refined court culture and impressive architectural works, including monumental castles that served both defensive and representative purposes.

This period was also characterized by greater openness to Western contacts and the introduction of new technologies, such as firearms. However, it was also a time that foreshadowed the subsequent period of isolation that occurred during the Tokugawa shogunate.

□ Muromachi Period (Ashikaga) (室町時代, Muromachi jidai)

Years: Approximately 1336 – 1573 CE

The Muromachi period begins with the establishment of the Ashikaga shogunate. It was a time of conflict and internal political struggles, and a period when the central authority of the shogunate weakened in favor of regional feudal lords, the daimyō.

Despite the political unrest, this was also a period of cultural and artistic flourishing, especially in the traditions of the tea ceremony, ink wash painting, and Noh theatre. The art of the Muromachi period was characterized by greater simplicity and subtlety, reflecting Zen influences.

The Muromachi period also saw the development of foreign trade, particularly with China and Southeast Asian countries. This was also the time of the first contacts with Europeans – the Portuguese, who arrived in Japan in 1543.

□ Kamakura Period (鎌倉時代, Kamakura jidai)

Years: Approximately 1185 – 1333 CE

The Kamakura period was a time when power shifted from the court aristocracy to the warrior classes. This marked the beginning of the era of samurai dominance in Japanese history.

Minamoto no Yoritomo established the Kamakura shogunate, the first military-feudal government in Japanese history. This was the start of a new form of governance, where the shogun was the de facto ruler of the country, despite the formal power of the emperor.

During the Kamakura period, there was a development of samurai culture, with a particular emphasis on the bushidō code. It was also a time when Zen Buddhism and Pure Land Buddhism (Jōdo) became popular among all social classes, introducing new aspects to Japanese spirituality and culture.

□ Heian Period (平安時代, Heian jidai)

Years: Approximately 794 – 1185 CE

The Heian period is considered the golden age of Japanese culture, art, and literature. It was during this time that works such as "The Tale of Genji" by Murasaki Shikibu, considered one of the world's first novels, were created.

A distinctive feature of the Heian period was the refined court culture, emphasizing aesthetics, poetry, and ceremonies. Although formal power remained in the hands of the emperor, real political power began to shift to the aristocracy and warrior clans.

The Heian period also saw the development of Japanese forms of Buddhism, such as Tendai and Shingon. The art of the period was dominated by subtlety, elegance, and detail, reflecting the refinement and taste of the Heian aristocracy.

□ Nara Period (奈良時代, Nara jidai)

Years: Approximately 710 – 794 CE

The Nara period is known for establishing the first permanent capital of Japan in Nara. It was a time of political consolidation, cultural and artistic development, mainly inspired by the Chinese model of the state. The Ritsuryō system, based on the Chinese legal system, was introduced. This system regulated aspects of political, social, and economic life, establishing a centralized, bureaucratic form of government.

Buddhism played a significant role in the cultural and religious life of the time. Numerous temples were constructed, and Buddhist art reached the height of its development. Some of the most important works of Japanese art and literature, including the first literary works written in the Japanese language, originate from the Nara period.

□ Asuka Period (飛鳥時代, Asuka jidai)

Years: Approximately 538 – 710 CE

The Asuka period was a time when further centralization of power occurred, along with the official introduction of Buddhism to Japan. Buddhism, brought from Korea, had a significant impact on Japanese culture, art, and religion.

Art during the Asuka period was characterized by strong continental influences and the development of a unique style. This era saw the construction of the first great Buddhist temples, as well as numerous sculptures and sacred art pieces.

The Asuka period witnessed key changes in the political and social structure, contributing to the formation of the classical Japanese state. It was then that the foundations for the later Ritsuryō system were laid, organizing Japanese society according to strict legal and administrative codes.

□ Kofun Period (古墳時代, Kofun jidai)

Years: Approximately 250 – 538 CE

The Kofun period is known for the development of large burial mound structures, called kofuns. These imposing constructions were intended for the elite, including clan leaders, indicating an increasing centralization of power and a growing social hierarchy.

This period saw the formation of a proto-state, with clear structures of governance. It was a time when Japan began to develop its unique identity, differentiating itself from continental influences. The Kofun period witnessed significant changes in art, religion, and society.

Despite a greater isolation from the Asian continent compared to the Yayoi period, contacts were not completely severed. Cultural influences from Korea and China continued, albeit to a lesser extent, impacting the cultural and technological development in Japan.

□ Yayoi Period (弥生時代, Yayoi jidai)

Years: Approximately 300 BCE – 250 CE

The Yayoi period was a time of significant social and technological transformations in Japan. The most crucial change was the introduction of rice cultivation, which had a profound impact on community organization and societal structure. Larger, more organized communities began to form, alongside the development of metallurgy, particularly the processing of bronze and iron.

During the Yayoi period, preliminary forms of statehood began to take shape. Society became increasingly complex, and a hierarchy emerged, leading to the establishment of the first forms of tribal and clan governance. This time also saw the formation of power patterns and influences, which eventually led to the creation of the Japanese state.

The Yayoi period also marked a time of increased contact with the Asian continent, especially with Korea and China. These contacts introduced new technologies, ideas, and cultural patterns to Japan, significantly influencing the further development of Japanese society and culture. These influences were visible in art, crafts, as well as political and religious systems.

□ Jomon Period (縄文時代, Jōmon jidai)

Years: Approximately 14,000 – 300 BCE

The Jomon period is recognized as the beginning of permanent settlement in Japan. It was characterized by a hunter-gatherer culture, with the beginnings of agriculture and permanent settlement. The population lived in small communities, building pit dwellings, and engaging in gathering, hunting, fishing, and primitive agriculture.

The art of the Jomon period is unique for its pottery, considered among the oldest in the world. Besides pottery, the Jomon people created figurines known as "dogū," which likely had a ritual significance. It was also a period in which early forms of religious beliefs and rituals began to take shape.

The Jomon period was marked by significant environmental diversity. Climate changes and the variety of local environments led to the development of various regional cultures in Japan. Over time, towards the end of the Jomon period, the first influences from the Asian continent began to appear, heralding changes that would occur in the subsequent Yayoi period.

Understanding Japanese History: All Historical Eras in Order (from 14,000 BCE to 2024)

Historical Jigsaw Puzzle

Immersing oneself in the history of Japan is like traveling through a complex yet fascinating labyrinth of time, where every corridor and turn hides extraordinary stories and cultural treasures. The history of this unique archipelago, stretching from prehistoric times to the modern Reiwa era, is like a richly illustrated chronicle, filled with events that have shaped not only the Japanese islands but also had an impact on the entire region and the world.

However, for many, even avid history enthusiasts, understanding and organizing this vast tapestry of time can be a challenge. The key to deciphering this puzzle lies in the knowledge of Japanese historical eras, which form the foundations supporting the entire narrative. Each era, from the ancient Jomon to the golden age of Heian, and up to the dynamic contemporary times, has its unique features and significance. These temporal divisions not only help organize the chronicle of events but also provide context, allowing for a better understanding of the social, political, and cultural transformations.

Let's take a bird's-eye view of the history of Japan, through all the historical eras in order, to arrange in our minds the sequence of changes in this country and be able to more easily place individual events, battles, or turning points in the broader context of Japan's historical continuum.

Today We Are in the 15th Era

Today We Are in the 15th Era

The Concept of Era in Japanese History

In Japanese historiography, long historical periods are referred to as "jidai" (時代). The kanji "時" (ji) means "time" or "epoch," and "代" (dai) means "generation" or "period." The term "jidai" literally translates to "epoch" or "period of time." It is a key element in organizing Japan's past, allowing for the division of history into clearly defined stages, each with its unique characteristics and significance. This system differs from "nengō," which refers to specific names of years and is associated with the reigns of emperors. "Jidai" allows historians and researchers to classify and analyze long periods in Japanese history, and each of these periods reflects significant changes in society, culture, politics, and economy.

Who and How Is an Era Determined?

In Japanese history, the change of long historical periods, known as "jidai," often correlates with significant social, political, or cultural changes. These periods are not officially established by the emperor or the government but rather emerge as a result of retrospective historical analysis. For example, historians may define a period based on the dominant form of governance, significant historical events, or changes in society and culture.

Thus, the division into "jidai" is more general and based on retrospective historical analysis, while "nengō" is a specific name for a year or series of years, officially established by the emperor. In our article, we will focus on "jidai," or long historical periods, being aware that there are also other methods of classification and division of Japanese history.

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Breaking Tradition in Naming

Breaking Tradition in Naming

Today We Are in the 15th Era

Today We Are in the 15th Era