In the Japanese Garden and in One’s Own Home

At dawn, the garden still slumbers, and yet something is already stirring within it. The wind, with the faintest of touches, sets the slender stalks of bamboo swaying, whispering to one another in a language of shadows and rustles, understood only by the patient ear. From the end of a bamboo spout, a drop of water falls, strikes the surface of a stone basin, and disperses into tiny, concentric ripples. In the depths of a pavilion, a furin – a wind chime – stirs, and its clear, crystalline tone cuts through the silence for a moment, only to vanish into it as though nothing had happened. These are sounds so subtle that they are easily overlooked if one lives in haste. And yet, in Japan, they are considered among the most precious of all.

At dawn, the garden still slumbers, and yet something is already stirring within it. The wind, with the faintest of touches, sets the slender stalks of bamboo swaying, whispering to one another in a language of shadows and rustles, understood only by the patient ear. From the end of a bamboo spout, a drop of water falls, strikes the surface of a stone basin, and disperses into tiny, concentric ripples. In the depths of a pavilion, a furin – a wind chime – stirs, and its clear, crystalline tone cuts through the silence for a moment, only to vanish into it as though nothing had happened. These are sounds so subtle that they are easily overlooked if one lives in haste. And yet, in Japan, they are considered among the most precious of all.

Why does Japanese culture place such value on what is fleeting, barely audible, and at times even on silence itself? In a world where noise has become the background to everyday life, these sounds are like delicate threads binding a person to the present moment. Japanese sensibility teaches that true meaning is not to be sought in what is loud and obvious, but in what demands attentiveness and an openness to “almost nothing” – for it is precisely there, in the realm of the senses, that fullness and harmony dwell. And above all – a connection with the present moment, so difficult for us to achieve, forever living as we do in plans for the future and in memories of the past.

Why does Japanese culture place such value on what is fleeting, barely audible, and at times even on silence itself? In a world where noise has become the background to everyday life, these sounds are like delicate threads binding a person to the present moment. Japanese sensibility teaches that true meaning is not to be sought in what is loud and obvious, but in what demands attentiveness and an openness to “almost nothing” – for it is precisely there, in the realm of the senses, that fullness and harmony dwell. And above all – a connection with the present moment, so difficult for us to achieve, forever living as we do in plans for the future and in memories of the past.

In today’s story, we will journey through the philosophy of sound – from Japanese gardens, spaces composed not only for the eye but also for the ear, through music in which silence can be as important as sound, to a philosophy of life in which everyday experiences can become like kaze no oto – the sound of wind, imposing nothing, yet stirring the deepest layers of the soul. It is a journey that may help us understand how listening attentively to what seemingly is not there can become a path to a fuller, calmer, and more conscious life – even if one lives far from Japan and its gardens. Perhaps here we may learn something new – for example, how to listen to the ticking of a clock, the soft crackle of wood in the fireplace, the occasional creak of the floor, or the echo of steps on a stairwell – in order to hear oneself.

The Japanese Sensitivity to Sound

The Japanese language, with its inclination toward poetic precision, possesses words that capture auditory phenomena with extraordinary subtlety. Kaze no oto (風の音) – “the sound of wind” – is not merely a sensory description but also a metaphor for impermanence, a sign that the world is in constant motion, though often imperceptibly so. Mizu no oto (水の音) – “the sound of water” – embraces everything from the gentle plash in a stone basin to a stream whose rhythm composes its own natural music. Both terms speak of a mode of listening that is mindful, almost contemplative, in which sound is not background but a gateway to a deeper experience of the moment. They are complemented by ma (間) – a concept with no exact equivalent in Western languages, meaning “the space” or “silence” between sounds. In music, in nō theatre, and even in daily conversation, ma is not an absence but a presence – a breath that allows what has already been spoken or played to fully resonate.

The Japanese language, with its inclination toward poetic precision, possesses words that capture auditory phenomena with extraordinary subtlety. Kaze no oto (風の音) – “the sound of wind” – is not merely a sensory description but also a metaphor for impermanence, a sign that the world is in constant motion, though often imperceptibly so. Mizu no oto (水の音) – “the sound of water” – embraces everything from the gentle plash in a stone basin to a stream whose rhythm composes its own natural music. Both terms speak of a mode of listening that is mindful, almost contemplative, in which sound is not background but a gateway to a deeper experience of the moment. They are complemented by ma (間) – a concept with no exact equivalent in Western languages, meaning “the space” or “silence” between sounds. In music, in nō theatre, and even in daily conversation, ma is not an absence but a presence – a breath that allows what has already been spoken or played to fully resonate.

The history of this sensitivity reaches deep into the spirituality of Japan. In shintō, every element of nature – wind, water, trees – can be the dwelling place of a kami, a divine spirit. Sound, therefore, is a trace of the invisible’s presence. The rustle of leaves in a shrine grove, the plash of water in a chōzubachi (a stone basin for the ritual washing of hands), or the beat of a taiko drum during a matsuri are not merely acoustic impressions – they are signs that the spiritual and human worlds are, in that moment, intertwined. Zen, on the other hand, emphasises the value of silence, not as emptiness but as a space filled with potential – a place where one can “hear” the mind itself. In the practice of zazen, even the most inconspicuous sound – the drip of water from a bamboo pipe, the echo of footsteps in a corridor – becomes an object of mindfulness, allowing for full immersion in the present moment.

The history of this sensitivity reaches deep into the spirituality of Japan. In shintō, every element of nature – wind, water, trees – can be the dwelling place of a kami, a divine spirit. Sound, therefore, is a trace of the invisible’s presence. The rustle of leaves in a shrine grove, the plash of water in a chōzubachi (a stone basin for the ritual washing of hands), or the beat of a taiko drum during a matsuri are not merely acoustic impressions – they are signs that the spiritual and human worlds are, in that moment, intertwined. Zen, on the other hand, emphasises the value of silence, not as emptiness but as a space filled with potential – a place where one can “hear” the mind itself. In the practice of zazen, even the most inconspicuous sound – the drip of water from a bamboo pipe, the echo of footsteps in a corridor – becomes an object of mindfulness, allowing for full immersion in the present moment.

This sensibility rests upon two pillars of Japanese aesthetics: mujō – impermanence – and wa – harmony. Mujō teaches that every sound is unique: the sound of the wind in the morning will never be identical to that of the previous day, and the echo of a drum in the mountains resounds differently than it does in a temple courtyard. This awareness of impermanence creates the desire to fully inhabit the present. Wa, in turn, dictates that every sound must coexist with its surroundings rather than dominate them – hence in traditional gardens, one composes not only visual but also soundscapes: the placement of a stream, the distance from a bamboo shishi-odoshi, even the species of trees whose leaves rustle in distinct ways. As a result, sound in Japanese culture is not merely a sensory stimulus but a philosophical vessel – something that teaches attentiveness, humility, and coexistence with the rhythm of nature.

This sensibility rests upon two pillars of Japanese aesthetics: mujō – impermanence – and wa – harmony. Mujō teaches that every sound is unique: the sound of the wind in the morning will never be identical to that of the previous day, and the echo of a drum in the mountains resounds differently than it does in a temple courtyard. This awareness of impermanence creates the desire to fully inhabit the present. Wa, in turn, dictates that every sound must coexist with its surroundings rather than dominate them – hence in traditional gardens, one composes not only visual but also soundscapes: the placement of a stream, the distance from a bamboo shishi-odoshi, even the species of trees whose leaves rustle in distinct ways. As a result, sound in Japanese culture is not merely a sensory stimulus but a philosophical vessel – something that teaches attentiveness, humility, and coexistence with the rhythm of nature.

The Garden as an Instrument

The Japanese garden is a work of art for all the senses. It is not created solely for the eye but also for the ear, which is to find within it a space for silence and the subtle resonance of nature. In the traditional concept of landscape, the garden master is not merely a gardener – he is a composer who selects sources of sound as carefully as he selects stones, moss, and sand. In his hands, the wind becomes a string, water a percussion, and silence – the purest of tones.

The Japanese garden is a work of art for all the senses. It is not created solely for the eye but also for the ear, which is to find within it a space for silence and the subtle resonance of nature. In the traditional concept of landscape, the garden master is not merely a gardener – he is a composer who selects sources of sound as carefully as he selects stones, moss, and sand. In his hands, the wind becomes a string, water a percussion, and silence – the purest of tones.

One of the garden’s most recognisable voices is 風鈴 (furin) – the wind chime. It originally came to Japan from China as fūtaku, a metal bell hung in Buddhist temples to ward off evil spirits. Over time, it changed shape and function, becoming a summer emblem of home verandas and gardens. Glass furin from Edo and the later Meiji period, painted with motifs of flowers or goldfish, were meant to cool the soul with their sound on hot days. In the Japanese imagination, its tone is ephemeral – as fleeting as an afternoon breeze that cannot be held. In the culture of kigo (seasonal poetic words), furin belongs to summer, and its sound often appeared in haiku as the record of a moment in which time slows down.

A more earthly yet equally rhythmic voice of the garden is 鹿威し (shishi-odoshi) – “deer-scarer.” This is a bamboo tube through which water slowly flows until, filled, it tips over, striking a stone with its characteristic clack before returning to its place to be filled again. In the mountains, it served to keep deer and wild boar away from crops, but in tea gardens it became an element of contemplation. This simple mechanism introduces into the space a regular, repeating accent – a distinct counterpoint to the unpredictable rustle of wind and the plash of water.

A more earthly yet equally rhythmic voice of the garden is 鹿威し (shishi-odoshi) – “deer-scarer.” This is a bamboo tube through which water slowly flows until, filled, it tips over, striking a stone with its characteristic clack before returning to its place to be filled again. In the mountains, it served to keep deer and wild boar away from crops, but in tea gardens it became an element of contemplation. This simple mechanism introduces into the space a regular, repeating accent – a distinct counterpoint to the unpredictable rustle of wind and the plash of water.

Even more subtle an instrument is 水琴窟 (suikinkutsu) – the “underground water koto” (koto being a stringed instrument). This is a clay vessel hidden beneath a stone basin (tsukubai, a basin for washing the hands), into which drops of water fall. Their sound, reflected and modulated by the hollow space of the vessel, emerges from the earth like the echo of an ancient song. A sensitive listener will detect in it qualities of yūgen – a mysterious depth that cannot be expressed in words – as well as ma, the silence between sounds in which the meaning of what is heard reverberates.

Even more subtle an instrument is 水琴窟 (suikinkutsu) – the “underground water koto” (koto being a stringed instrument). This is a clay vessel hidden beneath a stone basin (tsukubai, a basin for washing the hands), into which drops of water fall. Their sound, reflected and modulated by the hollow space of the vessel, emerges from the earth like the echo of an ancient song. A sensitive listener will detect in it qualities of yūgen – a mysterious depth that cannot be expressed in words – as well as ma, the silence between sounds in which the meaning of what is heard reverberates.

In the Japanese garden, sound does not always arise from what has been placed within it. It is often “borrowed” from the surroundings, in accordance with the principle of 借景 (shakkei – literally “borrowed scenery”). This is not only a visual landscape borrowed from beyond the wall – a mountain in the distance or a pine forest – but also sounds from outside the garden: the murmur of a nearby stream, the song of cicadas at midday in July, the wind rushing through the crowns of bamboo (or even the low hum of a modern, bustling station, as in Kyoto – 京都駅 空中経路 – “the garden on the roof of Kyoto Station”). The gardener can position gates, paths, and pavilions so as to amplify these distant sounds or bring them into the garden as if they were carefully chosen motifs in a composition.

Equally important is how the garden’s architecture guides sound. The arrangement of stones may direct an echo toward the tea pavilion, while clusters of bamboo can act as natural filters for the wind’s rustle. Water flowing over the smooth surface of stone sounds different from water that drips from a height onto fine gravel. In this way, the garden becomes an instrument upon which time and weather play – and the listener, if they know how to pause for a moment, becomes a co-performer in this concert.

Equally important is how the garden’s architecture guides sound. The arrangement of stones may direct an echo toward the tea pavilion, while clusters of bamboo can act as natural filters for the wind’s rustle. Water flowing over the smooth surface of stone sounds different from water that drips from a height onto fine gravel. In this way, the garden becomes an instrument upon which time and weather play – and the listener, if they know how to pause for a moment, becomes a co-performer in this concert.

Music of Wide Spaces

In the Japanese musical tradition, there is a concept that may surprise the Western listener: 間 (ma) – the space between sounds, which is just as important, and sometimes even more so, than the notes themselves. In the music of the shakuhachi – the bamboo flute used by komusō monks (虚無僧 – literally “monks of emptiness and nothingness”) – it is ma that allows breath and silence to weave themselves into the fabric of a piece. The shakuhachi never plays in an unbroken stream; phrases are interrupted by moments of respite, in which one hears only the wind, one’s own breath, or the distant rustle of leaves. These pauses carry a meditative quality – they separate and emphasise the sound, forming a complete whole with it. Similarly, in music for the 琴 (koto), the thirteen-stringed zither, and the 琵琶 (biwa), the lute used in epic storytelling, silence becomes a narrative tool, a breath between images, a way for the melody to linger in the listener’s mind before the next sound appears.

In the Japanese musical tradition, there is a concept that may surprise the Western listener: 間 (ma) – the space between sounds, which is just as important, and sometimes even more so, than the notes themselves. In the music of the shakuhachi – the bamboo flute used by komusō monks (虚無僧 – literally “monks of emptiness and nothingness”) – it is ma that allows breath and silence to weave themselves into the fabric of a piece. The shakuhachi never plays in an unbroken stream; phrases are interrupted by moments of respite, in which one hears only the wind, one’s own breath, or the distant rustle of leaves. These pauses carry a meditative quality – they separate and emphasise the sound, forming a complete whole with it. Similarly, in music for the 琴 (koto), the thirteen-stringed zither, and the 琵琶 (biwa), the lute used in epic storytelling, silence becomes a narrative tool, a breath between images, a way for the melody to linger in the listener’s mind before the next sound appears.

The same principles govern the music in nō theatre. Here ma is not limited to instruments – it also encompasses movement and gesture. The actor’s step is deliberately slow, and between one step and the next there is often a moment of stillness which, to the Western eye, seems to last longer than it should. The sound of the 小鼓 (kotsuzumi) or 大鼓 (ōtsuzumi) drums does not create a regular rhythm, but instead emerges at unpredictable intervals, often after silences so deep that the tension becomes thick, almost tangible. In nō, the point is not for music to “fill” time – rather, it opens fissures within it, through which something immaterial may enter: the echo of a step, the impression of a glance, the brush of air.

The same principles govern the music in nō theatre. Here ma is not limited to instruments – it also encompasses movement and gesture. The actor’s step is deliberately slow, and between one step and the next there is often a moment of stillness which, to the Western eye, seems to last longer than it should. The sound of the 小鼓 (kotsuzumi) or 大鼓 (ōtsuzumi) drums does not create a regular rhythm, but instead emerges at unpredictable intervals, often after silences so deep that the tension becomes thick, almost tangible. In nō, the point is not for music to “fill” time – rather, it opens fissures within it, through which something immaterial may enter: the echo of a step, the impression of a glance, the brush of air.

Many traditional composers sought to weave the rhythm of nature into their works. Pieces for shakuhachi may imitate the rustling of bamboo leaves, the sound of dripping water (mizu no oto – 水の音), or even the song of winter birds. Music here is not a closed whole but a dialogue with the surroundings – an outdoor performance becomes part of a larger symphony of the landscape. In this way, the listener is not a passive recipient but a co-creator. The emptiness of ma demands to be filled, but not with another note from an instrument – rather with what each person carries within: a memory, a breath, a sudden moment of illumination.

The Philosophy of Listening to Fleeting Sounds

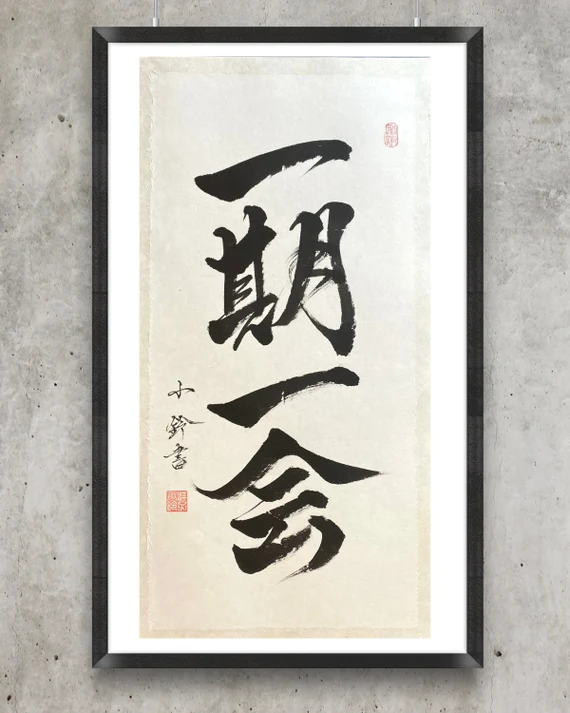

Sound is born, exists for the fraction of a moment, and disappears – leaving behind only a memory in the mind. In Japanese thought, this vanishing is the essence of its beauty, for it contains the truth of life itself. Every moment of hearing is unrepeatable, like a meeting described by the idiom ichigo ichie (一期一会) – “once in a lifetime, one meeting.” The drop that falls into the stone basin will never make the same sound again; the leaf that moved in the wind will never return to the same position. This awareness gives sound the dignity of something precious, demanding complete presence.

Sound is born, exists for the fraction of a moment, and disappears – leaving behind only a memory in the mind. In Japanese thought, this vanishing is the essence of its beauty, for it contains the truth of life itself. Every moment of hearing is unrepeatable, like a meeting described by the idiom ichigo ichie (一期一会) – “once in a lifetime, one meeting.” The drop that falls into the stone basin will never make the same sound again; the leaf that moved in the wind will never return to the same position. This awareness gives sound the dignity of something precious, demanding complete presence.

Silence in this tradition is not an absence, but a background that makes the perception of fleeting tones possible. In a zen garden, in everyday conversation, during a solitary walk through a winter forest – it is the pauses, the breaths, and the moments of suspension that create the conditions for attentive listening. The ability to be in silence is the art of allowing things to speak for themselves, without the constant need to comment or fill the space with words. In this way, hearing becomes a tool for understanding not only one’s surroundings but also oneself.

The act of hearing “silence” is one of the most subtle lessons Japanese aesthetics has to offer. It is the ability to perceive tension within stillness, to feel presence in the absence of sound, to recognise value in what is unforced and impermanent. In a world saturated with noise – both physical and informational – such an attitude can become a form of modern asceticism. By reducing the flood of stimuli, we learn to listen again: not only to the wind or the drops of water, but also to the quiet voices of our own thoughts and emotions, which in the din remain unheard.

The act of hearing “silence” is one of the most subtle lessons Japanese aesthetics has to offer. It is the ability to perceive tension within stillness, to feel presence in the absence of sound, to recognise value in what is unforced and impermanent. In a world saturated with noise – both physical and informational – such an attitude can become a form of modern asceticism. By reducing the flood of stimuli, we learn to listen again: not only to the wind or the drops of water, but also to the quiet voices of our own thoughts and emotions, which in the din remain unheard.

In Everyday Life

The sensitivity spoken of by Japanese gardens is not reserved for Kyoto or Kanazawa. It can be cultivated in Poland – in an apartment block, in a countryside home, on a walk through a park. All it takes is the willingness to listen to what usually remains in the background. The rustle of wind through maple leaves, the patter of rain on a windowsill, the silence after a downpour when the world seems to hold its breath – these are small experiences that become richer when we give them our full attention. They require no exotic scenery; only an open ear and mind.

The sensitivity spoken of by Japanese gardens is not reserved for Kyoto or Kanazawa. It can be cultivated in Poland – in an apartment block, in a countryside home, on a walk through a park. All it takes is the willingness to listen to what usually remains in the background. The rustle of wind through maple leaves, the patter of rain on a windowsill, the silence after a downpour when the world seems to hold its breath – these are small experiences that become richer when we give them our full attention. They require no exotic scenery; only an open ear and mind.

In daily life, so accustomed to a constant soundtrack, it is sometimes worth deliberately forgoing music, a podcast, or the television. Silence is not emptiness – it is the revealing of a backdrop in which subtle, natural sounds are hidden: the ticking of a clock, the quiet creak of wood in furniture, the echo of footsteps on a stairwell. It is the moment in which we realise that even “nothing” has its own tone.

In daily life, so accustomed to a constant soundtrack, it is sometimes worth deliberately forgoing music, a podcast, or the television. Silence is not emptiness – it is the revealing of a backdrop in which subtle, natural sounds are hidden: the ticking of a clock, the quiet creak of wood in furniture, the echo of footsteps on a stairwell. It is the moment in which we realise that even “nothing” has its own tone.

One can also create one’s own “sound gardens” at home – small arrangements that serve as sources of calm, repeating tones. A bowl of water into which a drop falls from time to time; a ceramic or metal bell hung by the window, stirred by every breeze; a simple, handmade instrument that becomes a focus for concentration. Such objects, though modest, set a mood and bring order into the chaos of the day.

The practice of listening can be an exercise inspired by zen: first, we focus on a single sound – the drops of rain, the hum of a fan, the breath. Then we move to silence, allowing it to fill the entire space. Finally, we turn our attention to the moment of transition – the boundary where sound vanishes and silence is born. This exercise teaches patience, presence, and sensitivity, which, over time, permeate all of life, helping us to hear more clearly both the world and ourselves.

Listening in the Void

Returning in thought to the image from the beginning – a leaf stirred by the wind – we now see it differently. It is no longer just a fragment of the landscape, but a point of contact between the world and ourselves. In its trembling lies the echo of all that is fleeting yet true: moments that cannot be held, yet can be accompanied. Listening to silence and to sounds that vanish in the blink of an eye is not an escape from life, but an entry into it more deeply, without the noise that blurs its outlines.

Returning in thought to the image from the beginning – a leaf stirred by the wind – we now see it differently. It is no longer just a fragment of the landscape, but a point of contact between the world and ourselves. In its trembling lies the echo of all that is fleeting yet true: moments that cannot be held, yet can be accompanied. Listening to silence and to sounds that vanish in the blink of an eye is not an escape from life, but an entry into it more deeply, without the noise that blurs its outlines.

It is a practice in which harmony arises not from excess but from renunciation; in which we learn to perceive rhythm not in the noise of events, but in the quiet pulse of existence. And though sounds will fade, and silence will change its shape, the sensitivity gained in such listening remains – like a quiet compass guiding one through everyday life.

Perhaps then, even today, wherever you are, you will hear something that until now has existed right beside you – patient, unforced, waiting for its first conscious “listening.”

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Turn off the world. Step into the water. Furo

Forest Bathing Shinrin-yoku – Breathe Among Japanese Cypress or Polish Beech Trees, and Let the World Wait

To See One’s Own Path Through the “Heavenly Bridge” in the Japanese Sumi-e Art of Master Sesshu

Japanese Karesansui Garden is a Mirror in Which You Can See Yourself

The Silence of Endless White – Winter Haiku as a Mirror of the Soul