Origami – A Paper Crane’s Bird-Eye View

What is Origami?

Origami, an ancient art of paper folding originating from Japan, is a field that continues to captivate and inspire across the centuries. Despite being deeply rooted in tradition and history, origami has evolved, transforming into a sophisticated form of artistic expression as well as an educational medium. In its simplest form, origami involves folding a single sheet of paper to create a three-dimensional figure, all without the use of scissors or glue. Present in Japan since the Heian period (794-1185), the art was initially reserved for religious ceremonies and rituals, eventually becoming accessible to all social classes.

Today’s origami goes beyond the physical folding of paper, extending into its digital interpretations in video games, animations, and manga. The art has become a narrative tool, a means of expressing emotions, and even an element of the plot, further enriching the tapestry of Japanese popular culture. In this article, we will delve into this fascinating evolution of origami, from its traditional roots through its role in art and culture, to its presence in the world of anime and video games.

Origami in Language

Origami in Language

The word “origami” comes from the Japanese words “ori” (折り), meaning “to fold,” and “gami” (紙), meaning “paper.” Known as origami (折り紙) in Japan, its roots extend further than Japanese culture, with the tradition of paper folding having its origins in China, where paper was invented around 105 A.D. However, it was in Japan that the art developed its unique form and significance.

Initially, due to the high cost of paper production, origami was an art form mainly accessible to the aristocracy, used in religious ceremonies and festive occasions. The term “origami” itself is a relatively new term that became popular in the 20th century. Previously, this art form was known as “orikata,” “orinuno,” or “orimono".

“Orikata” (折形): This term can be literally translated as “folded shapes” or “folded forms.” “Orikata” was one of the first terms used to describe paper folding in Japan, focusing primarily on the aesthetic and artistic aspect of the practice.

“Orinuno” (折り布): This term literally means “folded cloth,” referring to the tradition of folding fabrics, which is also an important aspect of Japanese culture.

“Orinuno” (折り布): This term literally means “folded cloth,” referring to the tradition of folding fabrics, which is also an important aspect of Japanese culture.

“Orimono” (折り物): This expression can be translated as “folded things” or “folded objects.” The term has a broader meaning and can refer not only to paper but also to the folding of other materials, such as fabrics. “Orimono” emphasized the practical aspect of folding, not just the aesthetic one.

Historical Paths of Origami

Introduction

At first glance, origami may appear to be merely a simple pastime, yet it is deeply rooted in the tradition and history of Japan. To comprehend how this art form became an integral part of Japanese culture, it is worthwhile to delve back into its origins and observe its evolution over the centuries.

The Beginnings of Origami in Japan

It is estimated that origami made its way to Japan around the 7th century, brought along with the introduction of paper by Buddhist monks. Originating from China, where paper was invented in 105 AD and the art was known as "zhezhi" (折纸), paper was a luxury item at that time, and the art of folding it was closely associated with religion and ceremonies. Folded models were used as offerings, protective amulets, and even as symbolic gifts during formal ceremonies.

The Differences between Origami and Zhezhi

The Differences between Origami and Zhezhi

While traditional Japanese origami focuses on folding a single sheet of paper without the use of scissors or glue, Chinese zhezhi often allows for cutting and gluing, which permits a greater variety and complexity in projects. Japanese origami has strong ties to culture, religion, and philosophy, playing a significant role in ceremonies and festivals, whereas Chinese zhezhi, although also rooted in tradition, has taken a more practical approach, being used to create toys, decorations, as well as in Chinese medicine and geomancy. In terms of aesthetics and style, origami often embodies simplicity and elegance, showcasing the beauty in the folding process itself, whereas zhezhi strives for more detailed and realistic representations, sometimes requiring additional techniques and materials.

The Connection with Religion and Ceremonies

Origami played a special role in Shinto, the indigenous religion of Japan. Folded paper figures, known as "shide", were often used in purification rituals, representing the spirit and power of deities. In Buddhism, folding paper had a meditative quality, helping monks to focus and achieve a state of inner peace.

The Development of Paper Folding Techniques

As time went on and the price of paper fell, origami became accessible to wider social classes. New folding techniques developed, and people began experimenting with different forms and styles. The first folding instructions emerged, allowing knowledge and skills to be passed down to future generations.

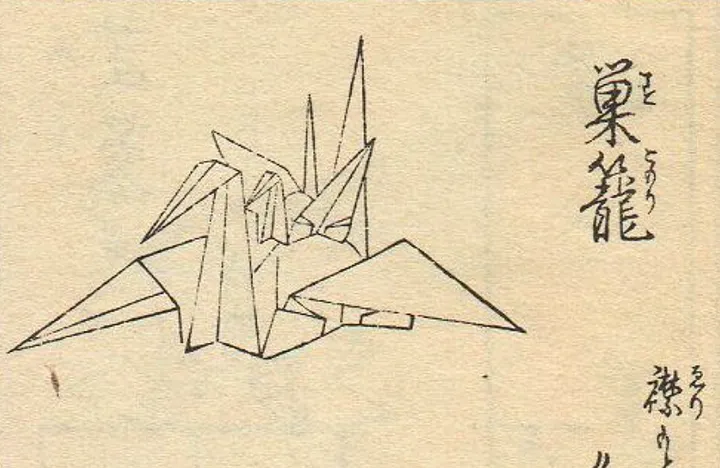

The Emergence of the First Instructions

The Emergence of the First Instructions

The first written origami instructions appeared in the 17th century, facilitating the standardization of techniques and styles. These early examples of origami literature helped transform the art into the form we know today, while also ensuring its preservation and transmission from generation to generation.

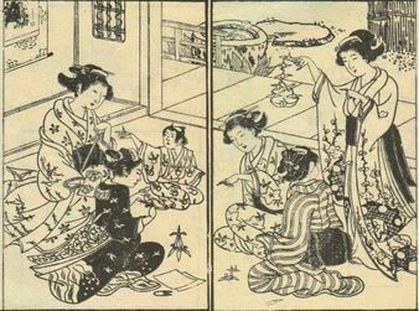

The Edo Period - The Golden Age of Origami

The Edo period (1603-1868) was a time of peace and stability in Japan, which fostered the development of art and culture. It was during this era that origami experienced its golden age. The art became popular among all social classes, from samurai to peasants, and the variety of forms and styles exploded. Many classic origami models that are still known and appreciated today were created during this period.

Breakthrough in Origami Art

The development of origami during the Edo period was crucial for its survival and subsequent flourishing. Throughout these years, origami transformed from a religious ritual and luxurious entertainment into an art form accessible to everyone, thus shaping today's Japanese culture. In this way, the foundations for future generations of origami creators were solidified, and this art form was ready to conquer the world.

Paper Spells: Applications of Paper Creations in Life

Paper Spells: Applications of Paper Creations in Life

Origami plays a significant role in education and child rearing in Japan, where it serves not only as a form of artistic expression but also as a tool aiding the development of motor skills, spatial awareness, and patience. Origami lessons are often incorporated into the curriculum in elementary schools, encouraging children to think creatively and work with precision. Additionally, the process of folding paper has a meditative quality, helping to calm the mind and increase concentration, which is particularly valuable in the fast-paced and sometimes stressful rhythm of life in Japan.

Origami in Art and Design

Origami in Art and Design

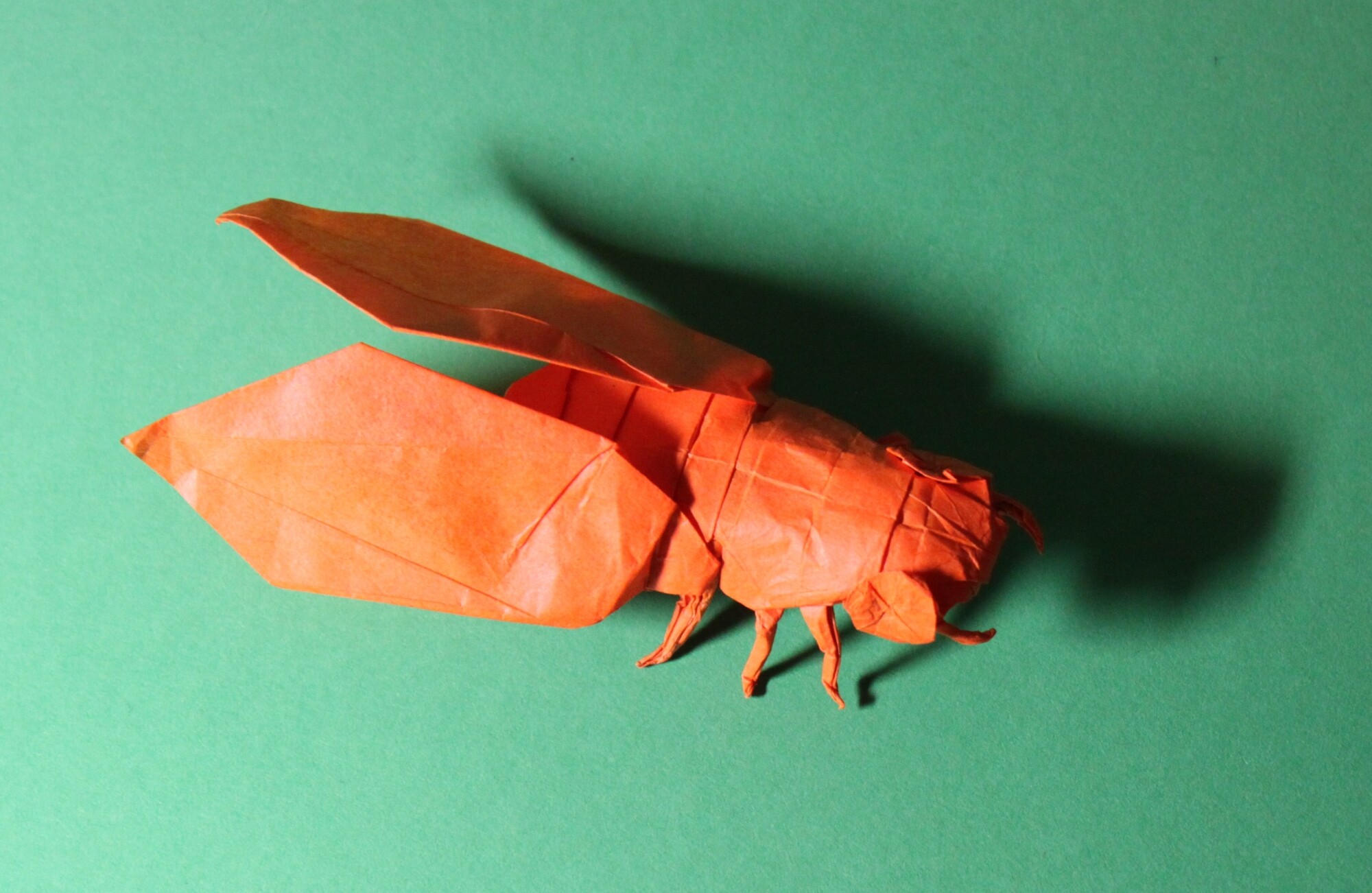

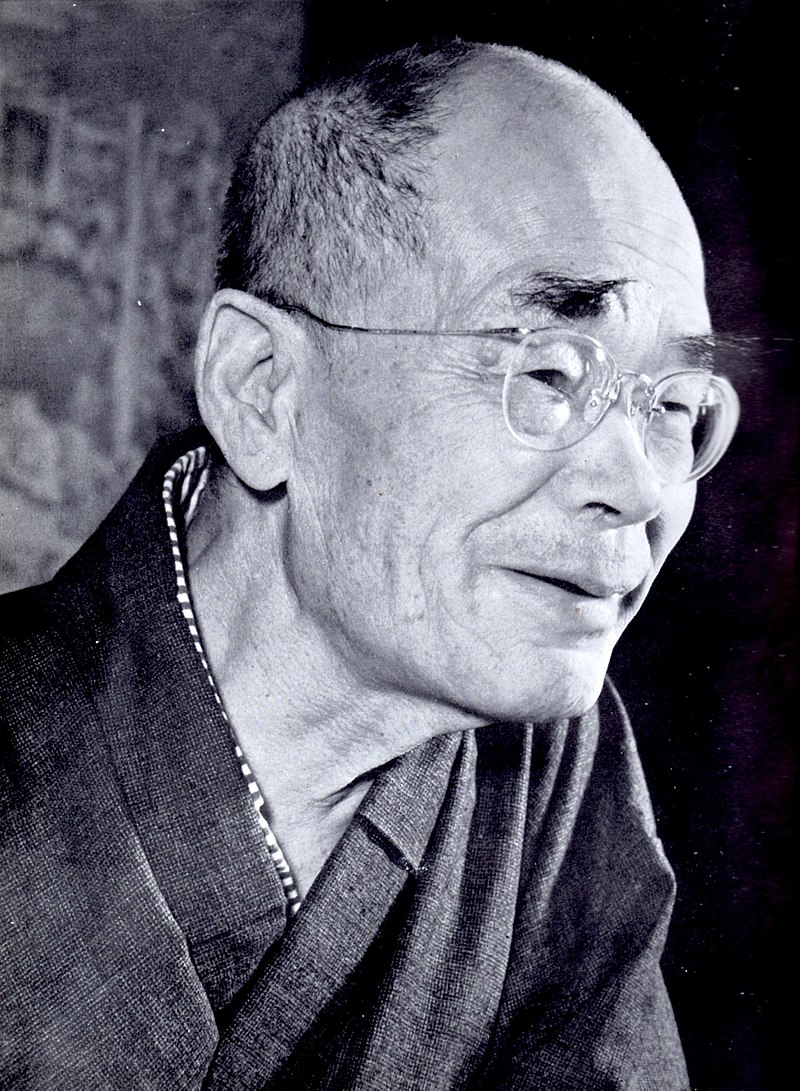

In the world of art, origami has gained recognition thanks to the work of artists like Akira Yoshizawa, considered the father of modern origami, who created over 50,000 models, introducing innovative folding techniques and notation. Another well-known creator is Satoshi Kamiya, famous for his complex and incredibly detailed models, such as his renowned dragon Ryu-Zin, requiring dozens of hours of work. Origami artist Robert J. Lang is famous for his approach that combines art with mathematics, creating intricate models based on folding theories and algorithms.

In architecture and design, origami has found application in creating innovative and functional structures that blend aesthetics with technology. Examples include the architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, which designed the "Origami" pavilion in Chicago, and the architectural office Buro Happold, which used origami techniques to create a foldable roof structure for a stadium in London. The use of origami in design is also visible in furniture projects, lamps, and other everyday items, where folded structures allow for innovative spatial and functional solutions.

Origami in Manga and Anime

Origami in Manga and Anime

Origami appears in many anime and manga, creating a unique atmosphere and adding depth to the narrative. In "Naruto," one of the main characters, Konan, uses origami as her combat technique, creating paper models capable of fighting and exploding. In "Cardcaptor Sakura," origami is used to create magical spells, and characters often fold paper figures with symbolic meaning. In "Death Note," origami is a visual element that helps build tension and a mystical mood in the series, which is a role that origami often plays in popular culture. In "Ranma ½," origami adds humor when characters fold absurdly complicated models in the middle of a fight.

Origami in anime and manga often serves to showcase the skills, character, or emotions of the characters. In "Fruits Basket," origami is used to show the delicacy and artistic sense of one of the characters, helping to build their characterization. In "Detective Conan," the ability to fold origami is used to solve criminal puzzles, highlighting the intelligence and perceptiveness of the main character. Folding paper can also serve to show calmness, patience, and sometimes even obsessiveness of the characters, adding depth to their psychological portraits.

In some anime and manga, origami serves to express symbolism and metaphor. In "Bleach," folding a paper crane is depicted as an act of mourning and remembrance for the deceased, which is deeply rooted in Japanese tradition. In "Tokyo Ghoul," origami represents the complex nature of humanity and its ability to create beauty, despite the presence of darkness and brutality.

The philosophy of origami

The philosophy of origami

The philosophy of origami is rooted in the idea of transformation and the possibilities that come with folding a flat sheet of paper into a three-dimensional object. This is a process that requires patience, precision, and an understanding of both the material and the technique. Many thinkers and artists have noted the meditative aspect of origami, emphasizing that folding paper requires concentration and calmness, which promotes achieving inner harmony. Philosopher and artist Akira Yoshizawa, considered the father of modern origami, spoke of "life in folded paper" and emphasized that every folded line or curvature has its own story and meaning.

Origami is also considered in the context of Zen philosophy, where great emphasis is placed on the creation process, rather than the final product. This is the idea that beauty and value are found in the present moment, in focus and dedication to the folding process. Such an approach to origami highlights its therapeutic and relaxing value, while also offering space for personal expression and creativity. Philosophers like Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, who popularized Zen in the West, emphasized that practices such as origami can help achieve the state of "satori," or enlightenment, through full engagement in the activity.

In the philosophy of origami, one can also see a reflection of the idea of "wabi-sabi," the Japanese aesthetic that finds beauty in impermanence, simplicity, and imperfection. Origami, being an ephemeral and delicate art, fits perfectly into these concepts, celebrating the modesty of the material and simplicity of forms. This way of perceiving origami emphasizes its role in shaping aesthetic and philosophical values, while encouraging reflection on the nature of existence and beauty.

Summary

Summary

Origami, as an art form that was born in simplicity and modesty, has survived the centuries, transforming and adapting to changing cultures and technologies. In today's world, where we are surrounded by digital media and the pace of life is accelerated, origami remains a breath of fresh air, an encouragement to slow down and find peace in the act of creation. It is an art form that not only connects generations but also builds bridges between cultures, showing that beauty and creativity can be found in the simplest forms. Origami, with its rich cultural and artistic heritage, is a living testimony that tradition and modernity can coexist in harmony, enriching each other.

Closing the journey through the world of origami, it is worth reflecting on how this ancient art of paper folding reflects the essence of the human spirit: our ability to create, adapt, and find beauty in simplicity. Origami, being both a form of meditation and artistic expression, remains an inexhaustible source of inspiration and tranquility, both in Japan and around the world. It reminds us of the strength that lies in silence, concentration, and simplicity. It is an art that teaches us that even from the simplest sheet of paper, something unique and meaningful can be created, serving as a beautiful metaphor for life itself.

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Origami in Language

Origami in Language “Orinuno” (折り布): This term literally means “folded cloth,” referring to the tradition of folding fabrics, which is also an important aspect of Japanese culture.

“Orinuno” (折り布): This term literally means “folded cloth,” referring to the tradition of folding fabrics, which is also an important aspect of Japanese culture. The Differences between Origami and Zhezhi

The Differences between Origami and Zhezhi  The Emergence of the First Instructions

The Emergence of the First Instructions  Paper Spells: Applications of Paper Creations in Life

Paper Spells: Applications of Paper Creations in Life  Origami in Art and Design

Origami in Art and Design

Origami in Manga and Anime

Origami in Manga and Anime  The philosophy of origami

The philosophy of origami Summary

Summary