Nō, Kyōgen, and Kabuki Reimagined: Traditional Japanese Theater in Contemporary Anime

Echoes of History: Medieval Theater on Anime Screens

Echoes of History: Medieval Theater on Anime Screens

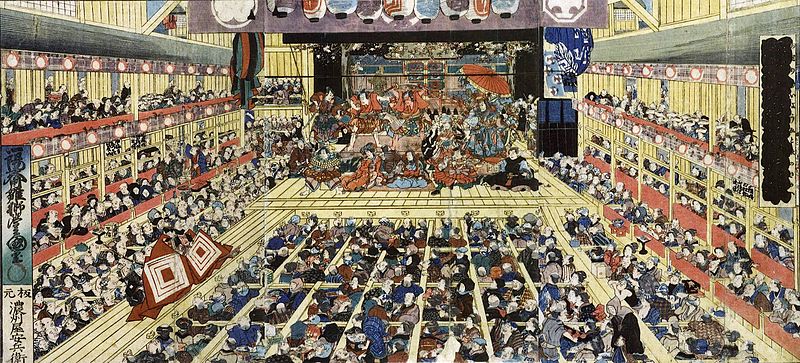

Japan offers the world a cultural heritage in which theater holds a prime position. Nō, the oldest of the sophisticated theatrical forms of the Land of the Rising Sun, represents the pinnacle of aesthetics and spirituality of the Muromachi period. Formed in the 14th century, Nō utilizes masks, gestures, and music to convey stories rich in metaphorical depth. Each performance is like a delicate dance between reality and the spirit world, giving viewers space for their interpretation. The unique symbolism and ambiance of Nō have not escaped the attention of anime creators, who draw from this theatrical form, transferring its subtlety and depth to the screen.

Kyōgen, often seen as the lighter counterpart to Nō, is a theater that laughs at everyday life. Originating from the same period as Nō, Kyōgen uses simpler language and more earthly themes, serving as a comedic interlude between the more dramatic Nō performances. It is an art of balancing sophistication with accessibility, where joke and satire become a means of conveying universal truths about human nature. In anime, the dynamism and humor of Kyōgen have found their reflection in exaggerated characters and situations, often providing a moment of relief in the tense narrative.

Anime creators adapt these traditional elements in their works, creating unique stories that speak to today's audiences as well as reflect the rich Japanese heritage. Understanding the roots of Nō, Kyōgen, and Kabuki allows for a deeper appreciation of how these timeless forms influence the aesthetics and narrative of contemporary anime films. Let's take a closer look at this.

Nō Theater – From Medieval History to Anime

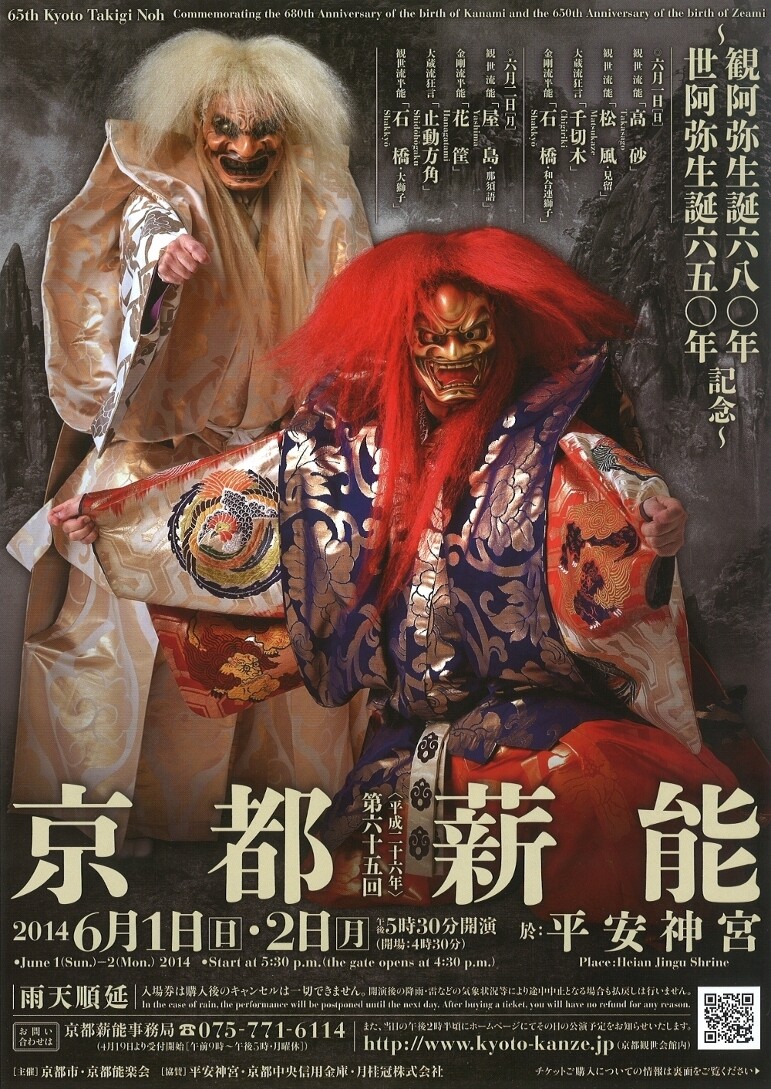

Nō theater, born from spiritual seeking and medieval rituals, is one of the most sophisticated and symbolic forms of drama in the world. The history of this art form dates back to the 14th century and is closely associated with names such as Kan'ami and his son Zeami, whose innovations and literary output ensured Nō an immortal position in the canon of Japanese art. Zeami not only introduced subtle rules of aesthetics known as "yūgen", which emphasize mysterious beauty and deep emotions, but also created many classic Nō works, like "Atsumori" or "Hagoromo", influencing Japanese culture to this day.

Transitioning to the world of anime, we see that the spirit and aesthetics of Nō are clearly present in many contemporary works. Anime like "Mononoke" utilize masks directly, drawing viewers into surreal stories full of spirits and demons that seem as if they have escaped straight from a Nō theater. The main character, a pharmacist who battles supernatural forces, often wears a mask that appears to be almost directly taken from a classic Nō performance, emphasizing his mysterious and immaterial character.

These examples show that although centuries separate Nō theatre from contemporary anime, the spirit of this classical drama form still lives on in modern adaptations and interpretations, remaining an invaluable source of inspiration for anime creators.

Kyōgen Theatre – 17th-Century Japanese Comedy and Satire in Today's Anime

Kyōgen is a Japanese theatrical form that developed as comedic interludes between serious and complex Nō dramas. They primarily served as a form of light entertainment, often with satirical elements, which were presented at feudal courts and temples. They provided a brief moment of relief and respite between the much longer and thematically heavier Nō performances. The works of creators like Izumi Kyōka and the role of renowned acting families, such as Nomura and Okura, have contributed to shaping this theatre. Kyōgen, though less known in the West than Nō, is extremely important for understanding Japanese humor and culture, focusing its themes mainly on human folly and ingenuity.

Moving to the world of anime, it is noticeable that the humor and narrative style borrowed from Kyōgen is present in many works. For example, the series "Gintama" perfectly reflects the comedic and often satirical spirit of Kyōgen. The plot frequently relies on absurd situations and exaggerated characters, which could just as well be found in a classic Kyōgen. The character of Gintoki, with his penchant for comic commentary and over-the-top reactions, is as if lifted straight from Kyōgen theatre.

"InuYasha" is another example where elements of Kyōgen can be seen in characters such as Miroku and Shippo, whose jokes and pranks are a nod to the light humor of Kyōgen amidst the more serious threads of the series. Their interactions with other characters often provide relief from the weight of conflict and drama, reminding the audience of the essence of human comedy.

Both "Gintama", "InuYasha", and "Ouran High School Host Club" show that anime draws from the tradition of Kyōgen not only through the adaptation of specific theatrical techniques but also by incorporating into the narrative the humor and lightness that can soften even the most dramatic moments. This testifies to the undiminished influence of Kyōgen on contemporary Japanese popular culture and the universality of Japanese humor.

Kabuki – The Third Pillar of Japanese Theatre

Kabuki theatre is one of the three major forms of classical Japanese theatre alongside Nō and Kyōgen. Its beginnings date back to the early 17th century, and its founder is recognized as Izumo no Okuni, a woman who created an innovative performative style combining dance with drama. Kabuki quickly gained popularity, particularly among the urban classes, becoming a form of folk theatre. Many Kabuki traditions, including the all-male cast (onnagata), were shaped by artists such as Sakata Tōjūrō I and Ichikawa Danjūrō I. Kabuki plays often explore themes related to morality, love, revenge, and duty, and their spectacular and expressive aesthetics are known worldwide.

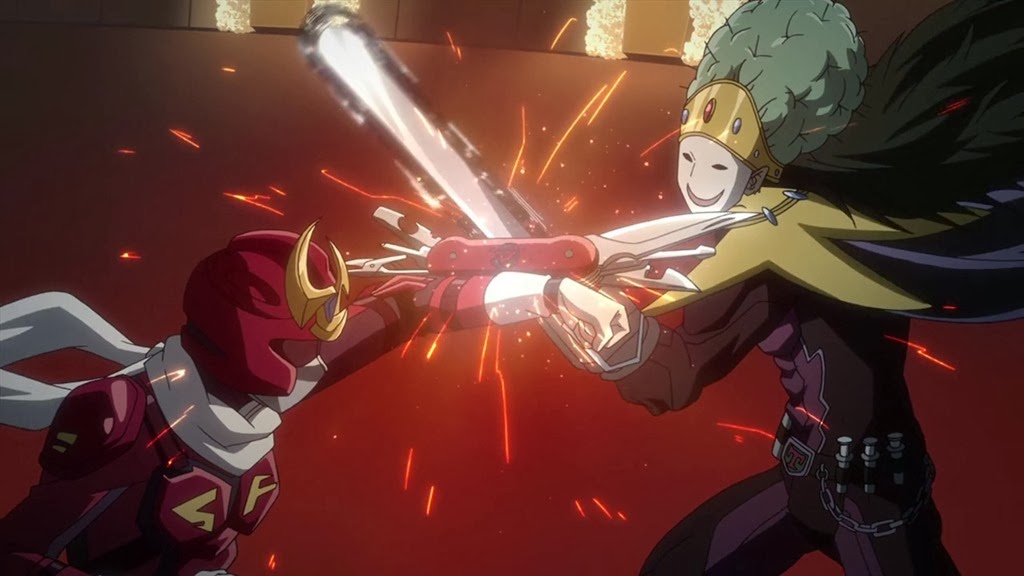

Anime, like Kabuki, often relies on distinctive characters and dynamic plots, making inspirations from this theatre readily apparent. "Katanagatari" is an anime that directly draws from the aesthetics of Kabuki, using exaggerated facial expressions and costumes that relate to traditional Kabuki attire. The dynamics of combat and the way emotions are expressed by the characters mirror the theatricality of Kabuki.

"Samurai Flamenco" is a modern interpretation of Kabuki themes, where the main character adopts the exaggerated and theatrical aesthetic of Kabuki to become a superhero. The visual styling of the characters and elements of their costumes are reminiscent of traditional Kabuki makeup and the characteristic storytelling style of the theatre, which is complex and full of twists and turns.

Inspirations from Kabuki in anime are evident not only in the visual aspect but also in character development, narrative, and the dynamics of storytelling, making it an important part of Japan's cultural heritage that continues to live on in modern media.

The Interplay of Theatrical Forms and Anime

Examples of anime narratives derived from theatrical forms

In the "Monogatari" series, dialogues and monologues are not only key to the narrative but also serve as a means of artistic expression, similar to the Noh theatre, where words carry deep metaphorical significance. "Monogatari" utilizes this technique to reveal the complex emotions and internal conflicts of characters. An example is a scene in "Bakemonogatari," where Koyomi Araragi and Hitagi Senjougahara engage in a lengthy dialogue during a meeting in a park, which holds both literal and symbolic meaning.

Comparing methods of presenting characters and emotions in theatre and anime

"Kabuki-bu!" is a literal fusion of Kabuki and anime, presenting the story of a group of high school students who form a Kabuki club. In this series, expressive makeup and costumes reminiscent of Kabuki are used to exaggerate character traits and emotions, typical of this theatrical form.

In "Princess Tutu," characters often express emotions through dance – a form akin to the dances in Kabuki, which are essential for expressing the inner state of a character. Each movement is meaningful, just like the precisely choreographed sequences in Kabuki.

Influence on Plot and Character Development

How traditional theatre influences anime plots

How traditional theatre influences anime plots

"Rurouni Kenshin: Tsuioku-hen" portrays the character of Kenshin in a manner reminiscent of Noh theatre, where his silence and calmness mask a tumultuous past and inner conflicts – similar to Noh masks that hide actors' emotions, allowing the viewer to interpret the depth of character.

In "Natsume's Book of Friends," the main character, Takashi Natsume, resembles a typical Noh protagonist whose encounters with spirits and attempts to understand their intentions and feelings reflect the spirit of this theatrical form, where the world of spirits and humans often intertwines.

In "xxxHOLiC," the character Yuko Ichihara often dons extravagant, theatrical costumes and is surrounded by a mysterious aura that recalls the dramatic style and presentation of Kabuki, serving to build her enigmatic nature.

Meanwhile, the series "Mushishi" utilizes motifs from Noh to build an atmosphere of mystery and connection with nature. The main character, Ginko, resembles a wandering Noh actor, whose interactions with mushi (ancient creatures) have profound metaphysical significance.

Aesthetics and Visual Language in Anime

Medieval Theater Aesthetics in Contemporary Anime

In "Hoozuki no Reitetsu," on the other hand, the character design and their expressive appearances are inspired by the aesthetics of Kyōgen and Kabuki, where each character has distinctly outlined makeup and costumes that reflect their personality and role in the story.

The Influence of Theater on Color, Composition, and Overall Visual Style in Anime

The anime "Mononoke" (not to be confused with "Princess Mononoke") is visually unique as it combines painting techniques with the aesthetics of Kabuki. The color scheme and character design are heavily inspired by traditional Japanese painting, and the methods of scene composition are reminiscent of theatrical settings.

"House of Five Leaves" ("Saraiya Goyou") is another anime that in its color palette and visual style resembles the canvases of the Edo period. The backgrounds and shots often have a theatrical, flat composition that echoes traditional theatrical scenography, especially that of Kabuki theater.

Optimistic Outlook for the Future

Optimistic Outlook for the Future

Contemporary anime continues to search for new ways of expression, often reaching into the rich heritage of Japan's traditional theatrical forms. Series like "Shouwa Genroku Rakugo Shinjuu" boldly explore both classic and innovative elements, demonstrating how the ancient art of storytelling can find its place in the modern world of animation. This hybrid narrative underscores that theatrical arts, though rooted in history, are ever-living, adapting to contemporary media and audience expectations. The future may bring even more such experimental combinations, where traditional methods will intertwine with digital innovations, creating entirely new audiovisual experiences.

Anime and traditional Japanese theater coexist, supporting each other, creating a cultural symphony that continues to evolve and surprise. Appreciating how Noh, Kyōgen, and Kabuki have not only survived in new forms but have become an integral part of Japanese animation allows us to look optimistically at the future of these traditional arts. It is not merely a matter of preserving heritage but also transforming and adapting it into new, exciting forms that will inspire generations of creators and audiences. This continuous renewal of tradition, the intermingling of forms and genres, is a testament not only to survival but to the ongoing flourishing of art, whose potential for further transformation seems almost limitless.

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Echoes of History: Medieval Theater on Anime Screens

Echoes of History: Medieval Theater on Anime Screens

How traditional theatre influences anime plots

How traditional theatre influences anime plots Optimistic Outlook for the Future

Optimistic Outlook for the Future