Mass Art in Japan: The Unbroken Chain from Ukiyo-e to Modern Manga

The Evolution of Japan's Visual Art

Japan, renowned for its rich artistic tradition, possesses a unique capability to intertwine ancient techniques with modern forms of expression. Two prime examples of this adaptability and transformation are Ukiyo-e and manga. Ukiyo-e, traditional Japanese woodblock prints from the Edo period, depicting scenes from the "floating world," laid the groundwork for many subsequent forms of Japanese visual art. On the other hand, manga, while deeply rooted in Japanese culture, draws inspiration from both traditional Japanese art forms and Western comics and animation.

Although these two art forms are separated by centuries and methods of creation, they share numerous similarities. Both Ukiyo-e and manga were crafted for a broad audience, reflecting the daily lives and aspirations of the Japanese during various historical epochs. Serving as mirrors to their respective times, these artistic mediums showcase the social, political, and cultural dynamics of Japan in their era.

Modern manga, while a product of contemporary times, owes much to its traditional predecessor. Ukiyo-e influences are evident in the themes, drawing styles, and storytelling techniques employed by manga creators. Through the analysis of these two art forms, one can understand how Japan, over the centuries, has melded tradition with modernity, producing unique and influential pieces of mass art.

Roots of Ukiyo-e and Manga

Since Ukiyo-e were mass-produced and relatively affordable, they became available to the wider urban population, making them the early "comics" for city dwellers. With the advent of the Meiji era (circa 1870), technologies like photography and lithography began to replace traditional woodblock print methods, but the spirit and aesthetics of Ukiyo-e persisted and evolved, influencing later art forms in Japan.

Manga, the contemporary Japanese comics, began taking shape post-World War II, with Osamu Tezuka, often dubbed the "father of manga," leading this evolution. Tezuka, inspired both by American comics and Disney animations as well as by traditional Japanese art and literature, innovated a fresh storytelling style. His works, such as "Astro Boy" and "Black Jack," have become cornerstones of modern manga.

While manga drew inspirations from Western sources, its roots delve deep into Japan's art history. Elements from emaki (Japanese scrolls from the 12th century), ezoshi (17th-century books), and satirical comics from the 1860s merge with Ukiyo-e influences, creating a rich backdrop against which modern manga unfolds. Despite the Western influences, manga remains deeply ingrained in Japanese tradition, amalgamating ancient techniques and motifs with contemporary expressions.

Visual similarities and differences

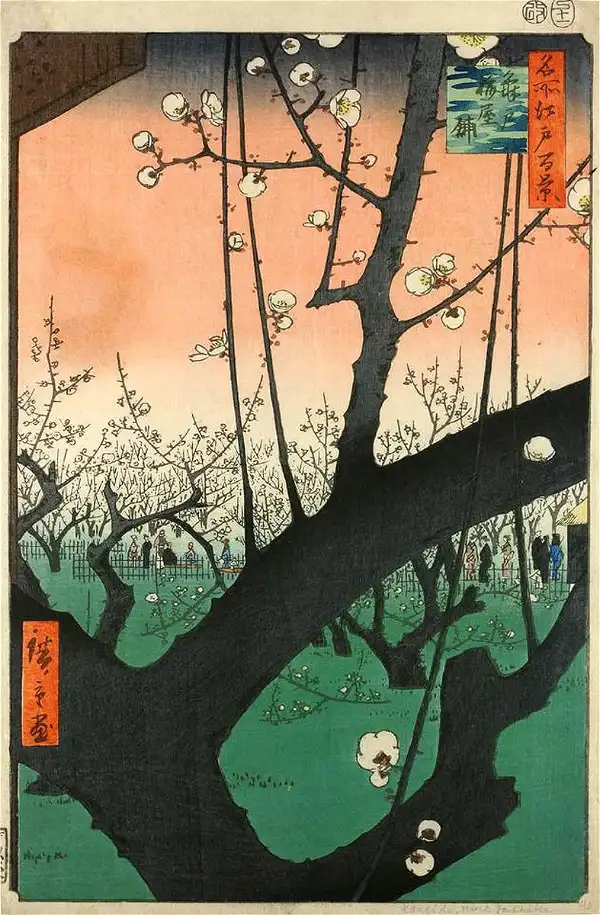

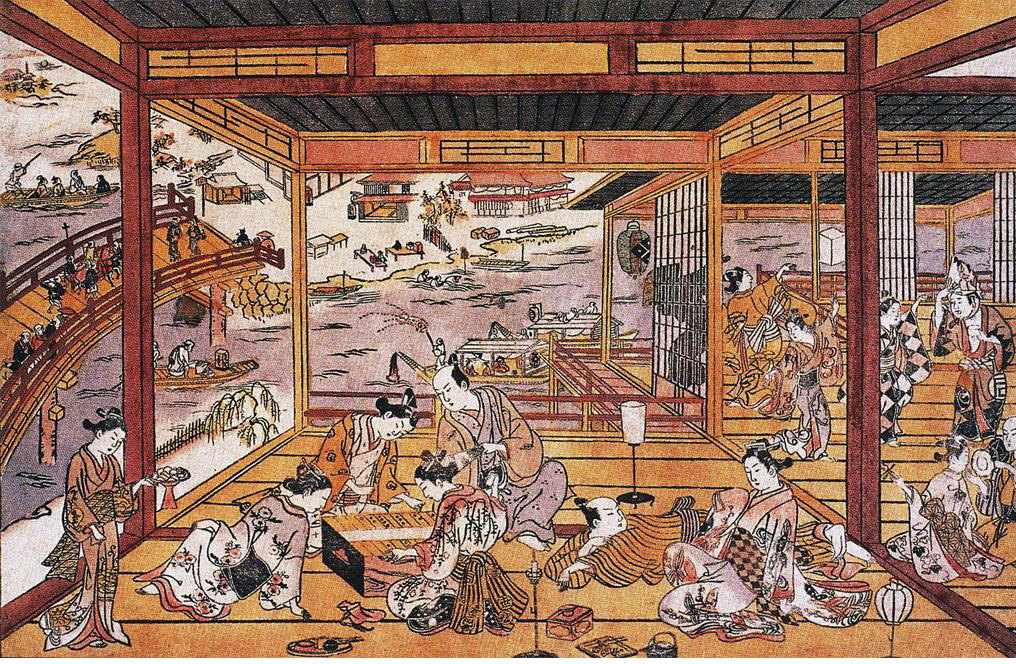

Technique and Style: Both ukiyo-e and manga are characterized by a specific, recognizable graphic style. In the case of ukiyo-e, dominant features include subtle lines, detailed backgrounds, and stark color contrasts, often using a limited color palette. Manga, on the other hand, usually employs more dynamic, exaggerated characters, especially for human figures, with their eyes being large and facial expressions distinctly outlined.

Nonetheless, both forms often utilize similar shading techniques and frame compositions. Examples of this can be seen in works like Hokusai's "The Great Wave off Kanagawa", where the dynamic composition of the wave echoes the dynamic battle scenes found in manga like Masashi Kishimoto's "Naruto".

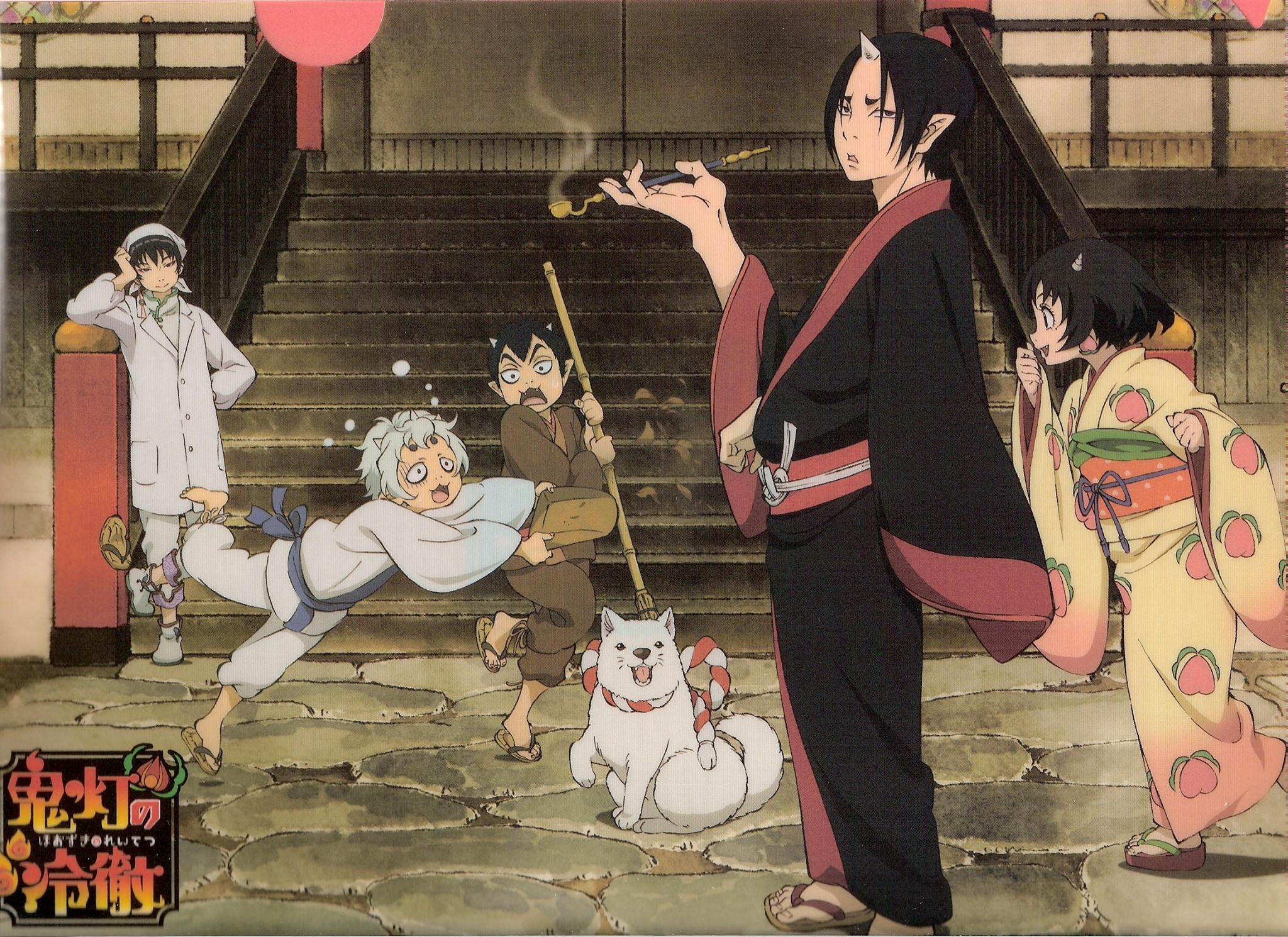

Themes: Both ukiyo-e and manga address many similar topics, ranging from everyday life and romances to supernatural phenomena. This allows both art forms to reflect the diversity of Japanese culture and history. For instance, themes of demons, spirits, and other supernatural entities are present in both traditional woodblock prints, such as the works of Yoshitoshi Tsukioka, and popular manga and anime like Yoshihiro Togashi's "Yū Yū Hakusho" or Koyoharu Gotouge's "Demon Slayer".

Themes: Both ukiyo-e and manga address many similar topics, ranging from everyday life and romances to supernatural phenomena. This allows both art forms to reflect the diversity of Japanese culture and history. For instance, themes of demons, spirits, and other supernatural entities are present in both traditional woodblock prints, such as the works of Yoshitoshi Tsukioka, and popular manga and anime like Yoshihiro Togashi's "Yū Yū Hakusho" or Koyoharu Gotouge's "Demon Slayer".

Narrative Conventions: Both art forms utilize images to tell stories, but they differ in their narrative presentation. In ukiyo-e, the story is often depicted in a single, intricate image that requires interpretation and contextual understanding. Manga, however, employs sequential frames that guide the reader through the entire story step by step. Although manga frequently uses text to complete the narrative, both forms primarily rely on visual communication. Works by Hiroshige, depicting various scenes from life during the Edo period, can be likened to epic tales portrayed in manga like Eiichiro Oda's "One Piece".

Visual Evolution: Over the years, both ukiyo-e and manga underwent many changes in style and technique. While early ukiyo-e were simple, focusing on individual figures or landscapes, later works became more intricate and layered. Similarly, manga, initially influenced by Western comics and Tezuka's simplistic style, has evolved to be more complex and diverse. An example of such evolution can be seen in the style difference between early manga like Tezuka's "Astro Boy" and modern works like Hajime Isayama's "Attack on Titan", characterized by more detailed graphics and intricate backgrounds.

M ass Production and Accessibility: From their inception, both ukiyo-e and manga served as primary tools for disseminating culture and stories among a broad audience. Ukiyo-e, as a woodblock print technique, allowed for mass production of images, which became primarily popular among the merchant class during the Edo period. Once luxurious and only available to the elite, they eventually became more affordable. For instance, woodblock prints by Hiroshige and Hokusai were widely circulated and became a part of daily life in Japanese bourgeois homes. Similarly, manga, initially as cheap comics sold at kiosks, gained popularity in the post-war years. Works like Osamu Tezuka's "Astro Boy" or later series like Akira Toriyama's "Dragon Ball" became known worldwide.

ass Production and Accessibility: From their inception, both ukiyo-e and manga served as primary tools for disseminating culture and stories among a broad audience. Ukiyo-e, as a woodblock print technique, allowed for mass production of images, which became primarily popular among the merchant class during the Edo period. Once luxurious and only available to the elite, they eventually became more affordable. For instance, woodblock prints by Hiroshige and Hokusai were widely circulated and became a part of daily life in Japanese bourgeois homes. Similarly, manga, initially as cheap comics sold at kiosks, gained popularity in the post-war years. Works like Osamu Tezuka's "Astro Boy" or later series like Akira Toriyama's "Dragon Ball" became known worldwide.

Ukiyo-e and manga were not just entertainment forms but also mediums of expression for socially marginalized groups. Ukiyo-e, depicting everyday scenes and figures from the lower social classes, acted as a form of resistance against the prevailing culture. They featured, for instance, kabuki actors, geishas, and even everyday scenes of bourgeois life, which were overlooked in traditional art. Manga, especially those targeting youth, often addressed social issues like inequalities, discrimination, or the challenges of growing up. Examples include manga like Keiji Nakazawa's "Barefoot Gen", showing the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, or Ichigo Takano's "Orange", addressing youth suicides.

Anime Drawing from Ukiyo-e Traditions

When we think of Japanese art and culture, both ukiyo-e and anime emerge as two of the most recognizable mediums—of the past and present respectively. In fact, many anime directly draw inspiration from the techniques, motifs, and aesthetics of ukiyo-e, creating unique works that blend tradition with modernity.

Certainly, one of the most notable examples of anime drawing from ukiyo-e is "Samurai Champloo" directed by Shinichiro Watanabe. This eclectic mix of hip-hop and Japan's Edo period frequently references ukiyo-e aesthetics in its visuals. The contrast of traditional battle scenes, like those seen in the works of Utagawa Kuniyoshi, with modern hip-hop elements creates a unique ambiance.

Another significant example is Studio Ghibli's "Princess Kaguya". Its distinct visual style is directly inspired by traditional Japanese painting techniques, especially ukiyo-e.

Anime "Mononoke" (not to be confused with Studio Ghibli's "Princess Mononoke") is a prime example of how traditional ukiyo-e techniques can be adapted into animation. The use of shading and colors reminiscent of traditional woodblock prints combined with motifs of spirits and monsters from Japanese mythology echoes the works of ukiyo-e artists like Tsukioka Yoshitoshi.

One of the most striking motifs in ukiyo-e are figures such as geishas, samurais, or mythical creatures. In the anime "Geisha Assassin", we witness the story of a young geisha seeking to avenge her father's death. Her appearance, attire, and surroundings are heavily inspired by ukiyo-e depictions of geishas.

One of the most striking motifs in ukiyo-e are figures such as geishas, samurais, or mythical creatures. In the anime "Geisha Assassin", we witness the story of a young geisha seeking to avenge her father's death. Her appearance, attire, and surroundings are heavily inspired by ukiyo-e depictions of geishas.

Meanwhile, the anime "Hoozuki no Reitetsu" portrays daily life in the Japanese hell, showcasing various mythical creatures and characters often found in traditional ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

Ukiyo-e: Social and Cultural Reflection

Ukiyo-e, literally translating to "pictures of the floating world", originated in the Edo period, a time when Japan experienced peace, urban development, and the rise of the merchant class. Initially accessible to the lower classes, these woodblock prints served as a counterpoint to the elite ink paintings with prevailing Chinese and Buddhist influences. Ukiyo-e showcased everyday life scenes, kabuki actors, beautiful women, and landscapes. Over time, it became a respected medium, moving from "low" to "high" culture.

Manga, like ukiyo-e, began humbly, initially perceived as entertainment for children. However, over the years, particularly post-World War II, manga blossomed, tackling mature and intricate subjects. Creators like Osamu Tezuka (often termed the "father of manga") transformed the medium, making it a critical component of Japanese pop culture.

Contemporary manga caters to various age groups and genders, from child-oriented "shoujo" and "shonen" to the more adult "seinen" and "josei". Such thematic diversity elevated manga from "low" to "high" culture status, akin to ukiyo-e.

Ukiyo-e and Manga: Two Sides of the Same Coin

Japan, a nation with deep traditions and a dynamic modern heritage, constantly seeks balance between its past and present. Ukiyo-e and manga represent two facets of the same coin. While centuries apart, both mediums encapsulate the spirit of Japanese culture: the ability to assimilate external influences while nurturing and renewing its intrinsic identity.

Ukiyo-e, with its subtlety and profound connection to nature, and manga, with its vibrancy and energy, together showcase the continuum of Japan's artistic heritage. They bridge the gap between ancient masters and modern creators, reminding us that art, regardless of its age or form, will always reflect the soul of a nation.

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Themes: Both ukiyo-e and manga address many similar topics, ranging from everyday life and romances to supernatural phenomena. This allows both art forms to reflect the diversity of Japanese culture and history. For instance, themes of demons, spirits, and other supernatural entities are present in both traditional woodblock prints, such as the works of Yoshitoshi Tsukioka, and popular manga and anime like Yoshihiro Togashi's "Yū Yū Hakusho" or Koyoharu Gotouge's "Demon Slayer".

Themes: Both ukiyo-e and manga address many similar topics, ranging from everyday life and romances to supernatural phenomena. This allows both art forms to reflect the diversity of Japanese culture and history. For instance, themes of demons, spirits, and other supernatural entities are present in both traditional woodblock prints, such as the works of Yoshitoshi Tsukioka, and popular manga and anime like Yoshihiro Togashi's "Yū Yū Hakusho" or Koyoharu Gotouge's "Demon Slayer". ass Production and Accessibility: From their inception, both ukiyo-e and manga served as primary tools for disseminating culture and stories among a broad audience. Ukiyo-e, as a woodblock print technique, allowed for mass production of images, which became primarily popular among the merchant class during the Edo period. Once luxurious and only available to the elite, they eventually became more affordable. For instance, woodblock prints by Hiroshige and Hokusai were widely circulated and became a part of daily life in Japanese bourgeois homes. Similarly, manga, initially as cheap comics sold at kiosks, gained popularity in the post-war years. Works like Osamu Tezuka's "Astro Boy" or later series like Akira Toriyama's "Dragon Ball" became known worldwide.

ass Production and Accessibility: From their inception, both ukiyo-e and manga served as primary tools for disseminating culture and stories among a broad audience. Ukiyo-e, as a woodblock print technique, allowed for mass production of images, which became primarily popular among the merchant class during the Edo period. Once luxurious and only available to the elite, they eventually became more affordable. For instance, woodblock prints by Hiroshige and Hokusai were widely circulated and became a part of daily life in Japanese bourgeois homes. Similarly, manga, initially as cheap comics sold at kiosks, gained popularity in the post-war years. Works like Osamu Tezuka's "Astro Boy" or later series like Akira Toriyama's "Dragon Ball" became known worldwide. One of the most striking motifs in ukiyo-e are figures such as geishas, samurais, or mythical creatures. In the anime "Geisha Assassin", we witness the story of a young geisha seeking to avenge her father's death. Her appearance, attire, and surroundings are heavily inspired by ukiyo-e depictions of geishas.

One of the most striking motifs in ukiyo-e are figures such as geishas, samurais, or mythical creatures. In the anime "Geisha Assassin", we witness the story of a young geisha seeking to avenge her father's death. Her appearance, attire, and surroundings are heavily inspired by ukiyo-e depictions of geishas.