Karuta: When Medieval Poetry Becomes a 21st-Century Japanese Sport

Masters of Reviving Tradition

In a Japanese High School, 2025

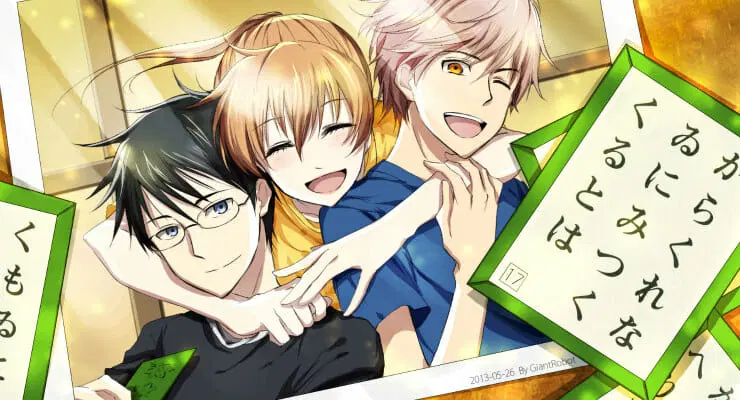

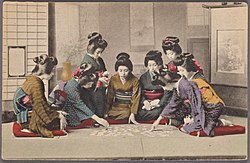

The gym smells of old varnish and tatami. Fluorescent lights buzz softly, and outside the windows, a fine October drizzle falls — as it often does in Kantō. Ten teenagers in tracksuits bearing the school emblem kneel opposite one another. Someone finishes a bottle of Pocari Sweat, another adjusts a mask already slid beneath the chin — a reflex left over from the pandemic years. On the wall hangs a poster of Ōmi Jingū drawn in anime style, alongside the black-and-red logo of the club: かるた部 (Karuta-bu).

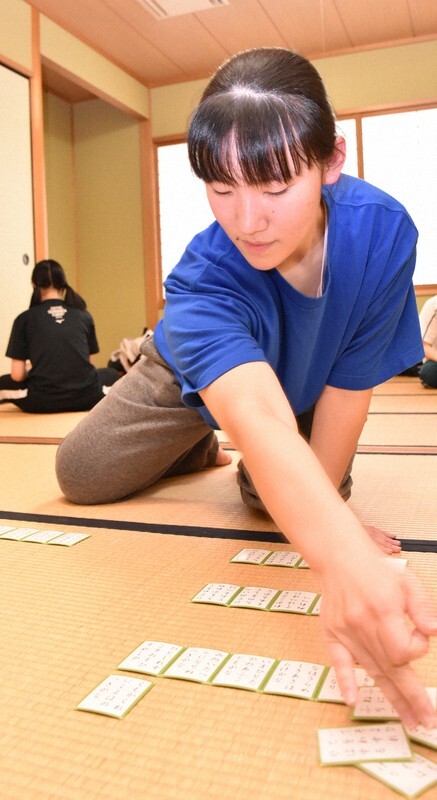

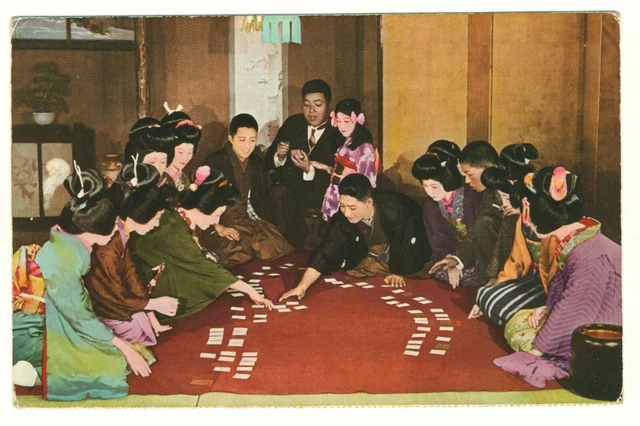

On the tatami lie rows of small, white cards. These are torifuda — “grabbing cards,” twenty-five per side. Between them runs the kūkan (空間) — a three-centimeter “corridor of air,” each row aligned as perfectly as a ruler’s edge. In the center sits the reciter — the yomite — the school’s English teacher, who chants entirely from memory. In his hand, he holds the yomifuda — “reading cards” with portraits of poets and the full text of the poems.

“Shokugyō an…” — he pauses abruptly. The students freeze, focused, silent. The teacher smiles. “Just kidding. But I see you’re all ready. Let’s start for real.”

First comes the jōgo — the warm-up poem, one not included in the hundred. It’s there just to help everyone catch the rhythm of the voice. Then silence again, like the tense pause before the starter pistol of a 100-meter dash.

- “…ki no…” — and then an explosion: two hands launch at once, cards slide across the tatami like thin petals of plastic, and there’s a sharp hiss of air. Who will touch the right one first? A student from the blue team knocks a card out of the playing zone — allowed. With a muffled roar of triumph (hushed, because “silence in the room!”) he sends one of his own cards to the opponent — “sending.” He’s now one card closer to clearing his field.

“Aki no ta no…” — autumn rice fields;

“…kariho no io no” — the reaper’s hut;

“…toma o arami” — the sparse thatched roof.

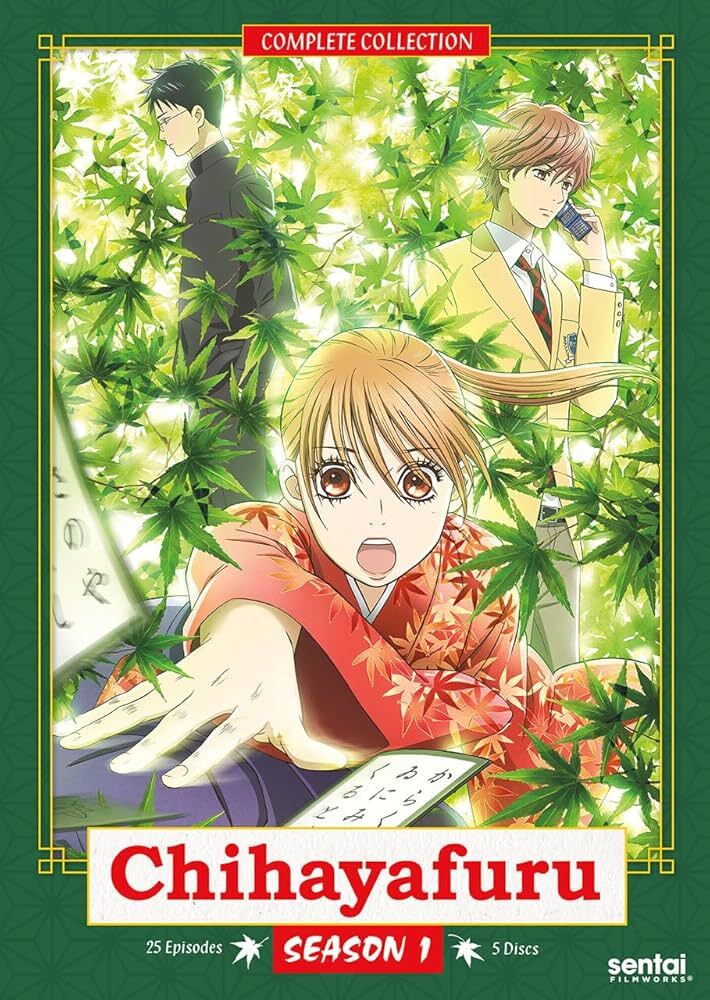

“Chihayaburu / kamiyo mo kikazu / Tatsutagawa…” — the boy in a T-shirt with “Chihaya” written on it (yes, from the anime Chihayafuru) waits for “kara-” and sweeps the card off the board in a flash. The teacher nods approvingly: good technique — a clean sweep on your own side is allowed, as long as you don’t touch an opponent’s card. The girl opposite him spreads her hands like wings over the cards — blocking with her gaze, rearranging the layout between turns (re-arrange is permitted), as though playing chess with space itself. Half a minute later comes “Hana no iro wa” — by the great poet Ono no Komachi. No one needs to hear the entire first line.

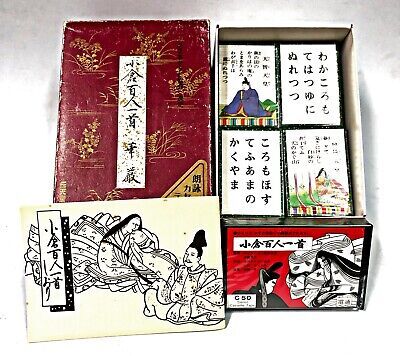

In the corner of the room sits a small Bluetooth speaker — the club’s warm-ups sometimes use the Karuta Chant or Wasuramoti apps, but during a match, the reading is always live. On the windowsill is a box from 大石天狗堂 (Ōishi Tengudō), the maker of official tournament cards. Beside it lies a stack of flashcards with kimari-ji, notebooks filled with handwritten calligraphy where someone is midway through copying out the entire hundred — just like the old-school study notebooks from Kinokuniya’s shelves. Phones are on airplane mode — no notifications to break the rhythm.

Only the Japanese can so seamlessly transform tradition into modernity: the medieval tanka becomes, all at once, a social game, a competitive sport, and a ritual of memory for 21st-century students. This isn’t an exaggeration or a literary trick — there are countless karuta clubs across Japanese schools, and after several hugely successful manga and anime series about Hyakunin Isshu, there are even more of them.

But let’s slow down. Step by step.

What exactly have we just witnessed?

“Hyakunin Isshu”

To truly understand what karuta is, we must step back nearly eight hundred years, to the beginnings of the Kamakura period, and in spirit even further — into the golden age of the Heian court. For karuta, though today a game and, in its competitive form, a dynamic contest, grows out of something much older and far more profound: poetry that for centuries has shaped the very core of Japanese sensibility.

- 百 (hyaku) — one hundred,

- 人 (nin) — people,

- 一 (i[chi]) — one,

- 首 (shu) — literally “head,” but in a poetic context meaning “poem” or “verse.”

百人一首, then, is “one hundred people, one poem each” — exactly what it is: a collection of one hundred poems written by one hundred different poets.

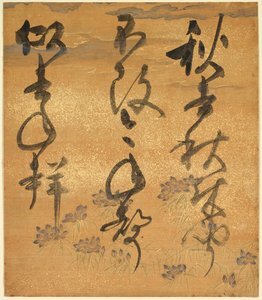

The form of every poem is uniform: each is a tanka (a type of waka), a short poem with a fixed meter of 5–7–5–7–7. Yet this selection of a hundred poems was anything but arbitrary — nor was it commissioned by imperial decree, as in the case of earlier official anthologies. Hyakunin Isshu is a representative anthology, a deeply personal selection by a master of words, not a collection assembled for the court.

The anthology spans poems from as early as the 7th century up to Teika’s own time. Side by side stand the verses of emperors, court ladies, hermit monks, warriors, and aristocratic poets. Within them lie poetic landscapes of the four seasons, intimate confessions of love and parting, reflections on impermanence, pilgrimages, temple visits, and memories of childhood.

This is not a uniform collection — it is a chest overflowing with worlds. Here are miniatures suffused with melancholy, heartrending confessions, delicate observations of nature, and subtle allusions to literature and history. It is precisely this diversity, combined with the harmony of Teika’s selection, that allowed Hyakunin Isshu to endure through the centuries as something more than just a book of poems. For the Japanese, it became a distilled image of the Heian spirit and the birth of a sensibility that, centuries later, came to be called mono no aware — an awareness of the fragility of all things, the tender sorrow of impermanence, and the fleeting beauty of the moment that is destined to vanish.

Poetry That Still Breathes

Imagine this: more than eight hundred years have passed, and Japanese high school students recite these poems from memory, competing to recognize a verse from a single syllable. The words of poets who lived at the imperial court in Kyoto (Heian-kyō) a thousand years ago become the starting signal for a 21st-century gymnasium match.

Let us take a closer look at one of these poems — the very first in the collection (we “heard” it earlier in our opening narrative):

秋の田の

かりほの庵の

苫をあらみ

わが衣手は

露にぬれつつ

Aki no ta no / kariho no io no / toma o arami / waga koromode wa / tsuyu ni nuretsutsu

“In the autumn fields,

in the reaper’s hut,

through the sparse thatched roof,

the sleeves of my kimono

grow damp with drops of dew.”

It is precisely at this boundary between past and present that the phenomenon of karuta unfolds. Hyakunin Isshu is not merely a book of poems; it is a living cultural heritage that the Japanese have carried from scrolls and calligraphy onto tatami mats, transforming it into a game, a sport, and a ritual of memory. We are accustomed to thinking that poetry this old belongs in dense academic treatises written by university historians of literature. Not in Japan. Here, these poems are shouted by laughing teenagers ready for “battle.”

Poems of Hyakunin Isshu — Examples

***

花の色は/移りにけりな/いたづらに/わが身世にふる/ながめせしまに

Hana no iro wa / utsurinikeri na / itazura ni / waga mi yo ni furu / nagame seshi ma ni

“The colors of the flowers

have faded — in vain,

while I, lost in my gaze at the rain,

have passed away with this transient world.”

— Ono no Komachi

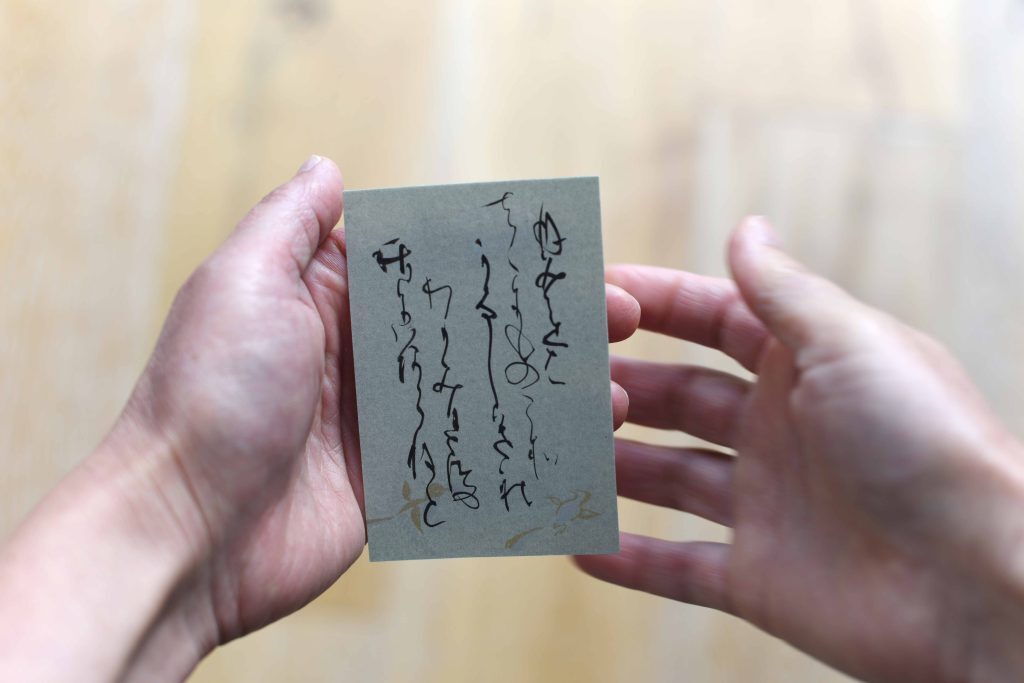

Komachi, a Heian-era poet and legendary beauty, weaves together the image of fading blossoms with the passing of her own youth. Nagame here is a kakekotoba — a poetic pivot word — meaning both “to gaze into the distance” and “to sink into wistful reverie.” In karuta, the initial “hana” is all that’s needed — and suddenly everyone hears the echo of a melancholy written over a thousand years ago.

***

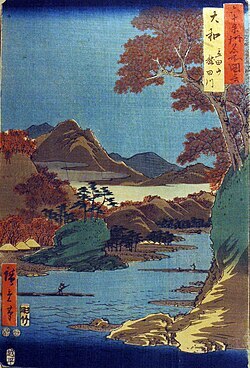

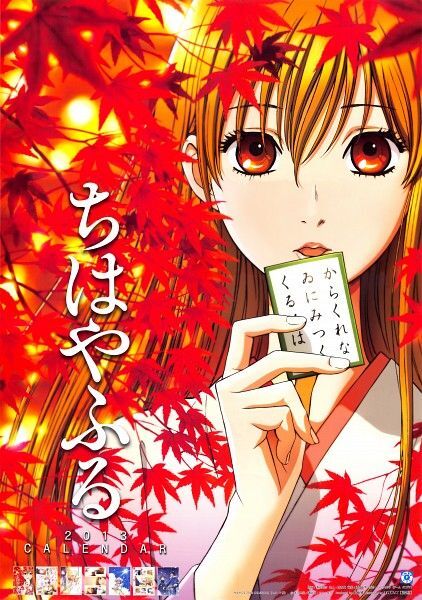

ちはやぶる/神代も聞かず/竜田川/からくれなゐに/水くくるとは

Chihayaburu / kamiyo mo kikazu / Tatsutagawa / karakurenai ni / mizu kukuru to wa

“Even in the age of the gods,

no one had ever heard

that the Tatsuta River

could bind its flowing waters

into a weave of crimson maples.”

— Ariwara no Narihira

Here, the image is almost painterly: the Tatsuta River flows among maples, its waters catching their scarlet hues, as though becoming a woven fabric itself. The epithet chihayaburu is an archaic expression denoting divine power, long unused outside poetry (until it resurfaced thanks to the popular anime Chihayafuru, whose title comes from this very poem). In karuta, this is one of the fastest cards: the opening “chi” is recognized instantly, and players’ hands shoot forward like arrows.

***

Konu hito o / Matsuho no ura no / yūnagi ni / yaku ya moshio no / mi mo kogaretsutsu

“I wait for someone

who never comes —

on the shores of Matsuho,

in the evening’s stillness,

I burn like salt upon the fire.”

— Fujiwara no Teika

The poem brims with longing and the slow burning of the heart. The speaker waits endlessly for someone who does not arrive, and this waiting is likened to salt roasting in flames, burning away to its essence. In karuta, this is a moderately challenging poem: the opening “konu” has several similar-sounding counterparts, so everything depends on a fraction of a second. It is also the closing poem of the entire anthology, written by Fujiwara no Teika himself, giving it symbolic weight — as though the compiler has bound the collection together with his own sigh of yearning.

Philosophy of the Hundred: Memory, Ephemerality, Everyday Life

Perhaps most fascinating is how these poems move from intimacy to community. Many were originally composed as private love letters, exchanged in secret among courtiers of the Heian era. They were meant to be a whisper between two people, not a national heritage. And yet over the centuries they became a foundation of education, an element of identity, and today — the very content of karuta clubs in Japanese high schools. It is a remarkable journey: from a thin sheet of paper bearing an intimate confession to the thunder of cards striking tatami in a hall full of teenagers. Hyakunin Isshu has endured because it could change its function while preserving its emotional core. Poetry that was once a whisper has become a shared ritual of memory. And perhaps that is the most beautiful thing — an intimacy that has become collective, yet has lost none of its fragility.

Karuta — How Did Medieval Poetry Become a Sport?

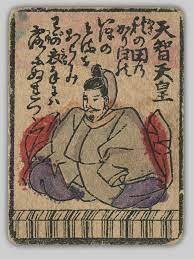

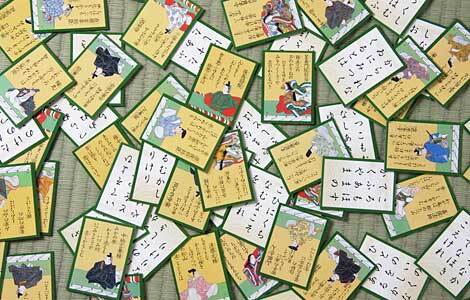

Today, if you walk into any bookstore in Japan — in Tokyo, Osaka, or Hakodate — just head to the “children and education” section and you’ll see entire shelves of uta-karuta sets. The most famous manufacturer, Ōishi Tengudō (大石天狗堂) of Kyoto, creates cards that look as if they came straight from an artist’s brush, preserving a style straight out of the Edo period. The portraits of poets on the yomifuda are pop-culture icons, repeated for centuries according to a single model that every Japanese child recognizes. And herein lies the phenomenon: thousand-year-old poems, medieval printing techniques, and the Portuguese word carta meet in the 21st century on tatami, in a junior high gym in Saitama, where someone sips Pocari Sweat and adjusts a school uniform sleeve before the next bout.

How to Play — Rules of Karuta

Karuta is a fast game that demands reflexes, memory, and concentration, yet its basic rules can be grasped in a few simple steps. The game uses two sets of 100 cards each:

- Yomifuda (読み札) — cards bearing a poet’s portrait and the full text of the tanka. These are the cards from which the poems are read.

- Torifuda (取り札) — the “cards to be taken,” containing only the last two lines of the poem.

Before the game begins, there are 15 minutes to memorize the layout. During this time, players learn the position of every card, relying on spatial memory. In the final two minutes, they may practice hand movement — the so-called “hand run-through” over the cards — preparing the body for a lightning-fast reaction.

There are also mistakes, called otetsuki:

- touching the wrong card,

- reaching for a card on the wrong side,

- reacting to a karafuda (a dead card),

- using both hands at once.

The penalties sting: for an error, your opponent “sends” you an additional card.

Though the official form, kyōgi karuta (競技かるた), is a one-on-one duel played under the rules of the All Japan Karuta Association, there are also variations. Genpei gassen is played in teams, while relay karuta introduces player substitutions during a match. For children, there are simplified games like bōzu-mekuri, where the cards are recognized by their illustrations rather than their poems. On Hokkaidō, a regional variant called shimo no ku karuta is popular, in which only the lower half of the poem is read — a system so confusing that switching to the northern version after playing on Honshū is notoriously difficult and slow.

Karuta as a Sport: Organization, Ranks, Tournaments, Heroes

A Renaissance in the 20th and 21st Centuries

The influence of Chihayafuru spread beyond Japan as well: the first karuta clubs appeared at universities in the United States, exhibition matches are held in Europe, and an active Reddit community now studies kimari-ji together.

“Sport or Culture?”

Within this unity lies an extraordinary sense of community. The poems of Hyakunin Isshu were born as intimate letters: confessions of love, reflections on impermanence, records of fleeting joys and sorrows. Their authors lived in a completely different world — ceremonial, palatial, separated from today by a thousand years of technological progress. And yet, the very same words, unchanged, now live on tatami mats, in school gymnasiums, in mobile apps, and in anime streamed on smartphones. Poetry that was once a lover’s whisper has become a shared ritual of memory, a code of recognition, and a way of connecting generations. It is one of the few examples in the world where a centuries-old language exists not just in libraries but in the hands of teenagers, listening intently for the syllables of medieval verse.

And this is the paradox of Japan — though, in truth, it’s not a paradox at all. A technologically advanced nation where children are taught to play with poetry from before the samurai era — a country where tradition pulses in step with modernity instead of fossilizing in museums. Karuta is neither a relic nor a reconstruction. It is a living practice of preserving meaning, a bridge between a world a thousand years gone and the reality of the digital age. In a country of shinkansen, omnipresent drones, artificial intelligence, and neon-drenched metropolises, high school students recite the verses of Fujiwara no Teika and Ono no Komachi as though time itself has paused.

Japan teaches us that tradition doesn’t need to be preserved like an artifact locked in a display case — you need only draw from it actively and sincerely.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Kemari – A Ball Game from Medieval Japan That Taught Self-Control Instead of Competition

Bo-Taoshi - A Japanese Team Sport That Breaks Safety Rules and Bones

Serious Snowball Fighting, Aka the Japanese Team Sport Yukigassen

Asuka – The Wild WWE Wrestler from Japan, Gamer, and Graphic Designer

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!