Kami, islands, chaos and ocean: World Creation Vision in Japanese Mythology

Island Myth

These tales mold the landscape of the Japanese Isles, influencing perceptions of nature, natural occurrences, and human experiences. Their echoes are evident in Japanese art, literature, and festivals, which have been integral to the nation's traditions for centuries.

Though many of these legends hail from a distant past, they retain their relevance. Contemporary Japanese society remains steeped in the symbolism and rituals of these tales, bridging the chasm between antiquity and modern life in Japan.

Kojiki and Nihon Shoki: Stone Pillars of Japanese Heritage

The Kojiki, also known as "Records of Ancient Matters", is Japan's oldest extant text, penned in 712 AD by order of Empress Gemmei. It chronicles the genealogy of the imperial family and myths about the inception of the world and the birth of the Japanese archipelago. Much of the Kojiki revolves around tales of deities like Izanagi and Izanami, credited with the creation of the Japanese islands.

Conversely, the Nihon Shoki, dating back to 720 AD, stands as Japan's second-oldest historical text. Commissioned by Emperor Tenmu, it delves deeper and is more detailed than the Kojiki, encompassing not only myths but also specific histories of Japan, beginning with the legendary Emperor Jimmu. While both texts explore similar subjects, their nuances differ, making them invaluable resources in studying Japanese heritage.

Over centuries, these texts transformed from merely religious and historical knowledge sources to muses for numerous artists, poets, and writers. Works like the "Man'yōshū" - the oldest anthology of Japanese poetry, and Nō dramas drew inspiration from them, producing pieces reflecting the profound spiritual and cultural values of Japan.

Universe from Chaos: The Primordial Birth

Before the universe materialized as we know it, Japanese mythology depicted it as a wild, untamed chaos. An infinite space where a smattering of particles and light began moving, establishing the first elements of reality. This light, rising faster than the denser particles, ascended above the universe, while the lighter particles soared, forming clouds called takamagahara - the High Plain of Heaven. The heavier particles, incapable of ascension, congregated below, creating the terrestrial mass.

The Birth of the First Gods: Kotoamatsukami

In Japanese mythology, the emergence of the kotoamatsukami not only marked the universe's beginning but also laid the foundation for its further evolution. Though these five deities aren't frequently mentioned in subsequent myths, they remain essential for understanding the significance of beginnings in the Japanese worldview.

Over time, after the kotoamatsukami concealed themselves, more deities emerged, including two more hitorigami and five male-female deity pairs. These pairs, serving dual roles as couples and siblings, played a pivotal role in the ongoing evolution of Japanese cosmogony, ushering in the birth and development of the earthly realm.

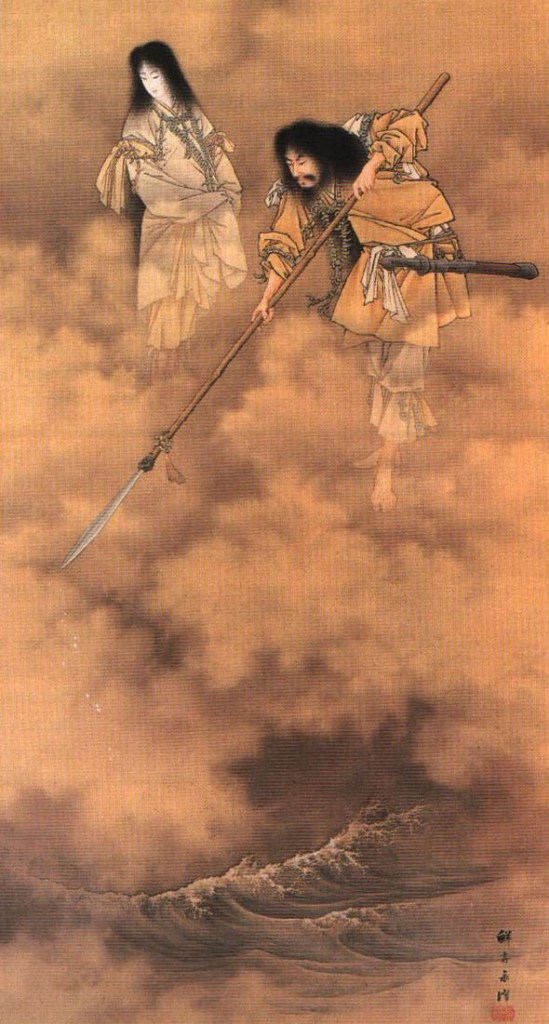

Creation of the Archipelago: Birthplace of the Sun God

According to Japanese mythology, following the birth of the primary deities came the inception of the first lands. Central to this process were Izanagi and Izanami, siblings and concurrently, a couple, who were entrusted with a celestial jewel and a spear by elder deities. When they swung this spear over the primordial ocean, droplets falling off it created Japan's first island – Onogoro. It was on this island that the romantic unions between Izanagi and Izanami became the foundation for the birth of numerous other deities and kami, as well as the archipelago itself.

According to Japanese mythology, following the birth of the primary deities came the inception of the first lands. Central to this process were Izanagi and Izanami, siblings and concurrently, a couple, who were entrusted with a celestial jewel and a spear by elder deities. When they swung this spear over the primordial ocean, droplets falling off it created Japan's first island – Onogoro. It was on this island that the romantic unions between Izanagi and Izanami became the foundation for the birth of numerous other deities and kami, as well as the archipelago itself.

Heart of Identity: Islands as a National Symbol

The islands, which formed from the love of these two deities, not only constituted the physical foundation of the country but also deeply rooted in the cultural identity of Japan. Each of the main islands – Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku – has its unique history and significance, reflecting the diversity and richness of Japanese culture and traditions. These islands have become a symbol of national unity and continuity, while simultaneously highlighting the country's uniqueness in the surrounding world.

Kami: Spirits that Shape the World

After the creation of the islands, Izanagi and Izanami continued the creation process, giving life to many kami. In Japanese tradition, kami are gods or spirits that inhabit various elements of the world, from natural formations like mountains or rivers to objects and concepts. Their omnipresence and diversity reflect the harmony and closeness between the natural world and humans in Japanese culture. As the number of kami grew, so did their influence in shaping the world. Some, such as Amaterasu, the sun deity, became central to the Japanese pantheon and played a pivotal role in the country's subsequent myths and legends. Their interactions, conflicts, and alliances directly impacted the development of the world and people, emphasizing the continuous dynamic between the gods and reality.

Origin of the Three: The Beginning of a New Era in Mythology

After performing a cleansing ritual by the river, Izanagi gave life to three new deities. From his left eye, Amaterasu, the sun goddess, was born, becoming a central figure in the Japanese pantheon. From his right eye came Tsukuyomi, the moon god, and from his nose, Susano'o, the god of storms and the sea. These three deities not only became the most crucial figures in Japanese mythology but also reflected fundamental aspects of nature and human life.

Amaterasu: The Light that Leads the Nation

Amaterasu: The Light that Leads the Nation

Amaterasu, with her bright and benevolent nature, became a symbol of unity, peace, and harmony. She is best known for the legend of hiding in a cave when her brother, Susano'o, drove her to despair with his behavior. Her return, provoked by the intrigue of other deities, brought light back to the world, symbolizing renewal and hope. Amaterasu is also the ancestor of the Japanese imperial family, making her a significant figure in the country's history and identity.

Tsukuyomi: The Mysterious Power of the Night

Tsukuyomi, while less known, is an equally significant deity. His dominion over the night and mystery contrasts the brightness and openness of his sister, Amaterasu. One of the most famous myths associated with Tsukuyomi speaks of how he killed the food goddess, Uke Mochi, leading to his permanent separation from Amaterasu, symbolizing the division of day from night.

Susano'o: Unpredictability and Transformation

Susano'o: Unpredictability and Transformation

Susano'o, the most controversial of the trio, represents aspects of storms, the sea, and other forces which, although powerful and sometimes destructive, are essential for the life cycle. While often portrayed as a problematic figure, especially in conflict with Amaterasu, Susano'o also has moments of heroism, like when he defeated the eight-headed dragon, Orochi.

Cultural Icons: The Influence of the Three on Japan

The significance of these three deities in Japanese culture cannot be overstated. Their stories, values, and symbolism are reflected in many aspects of daily life, from festivals and religious rites to literature and art. They are not only central figures in mythology but also a source of inspiration and reflection for many generations of Japanese.

Mythology in Anime

"Noragami": Gods Among Humans

One of the most striking animes based on Japanese mythology is "Noragami". The main character, a god named Yato, wishes to become more well-known and worshiped. To achieve this, he performs various small tasks for people. Although "Noragami" portrays a modern world, numerous elements of traditional Japanese mythology intertwine with the plot, introducing different gods, spirits, and rituals.

"Kamisama Kiss": Romantic Entanglements with Kami

"Kamisama Kiss": Romantic Entanglements with Kami

The anime "Kamisama Kiss" tells the story of a high school girl, Nanami, who becomes a land deity after kissing a god named Mikage. Throughout the series, Nanami meets various figures from Japanese mythology, learning about her new role as a deity, while also grappling with feelings for her servant, Tomoe, who is a fox-demon.

"Natsume's Book of Friends" Legacy and Spirits

In "Natsume's Book of Friends," the protagonist, Takashi Natsume, inherits the ability to see spirits from his grandmother. Along with a book that contains the names of spirits who once served her, Natsume encounters various characters and entities from Japanese mythology. Each episode often focuses on individual spirit stories, showcasing the diversity and depth of traditional Japanese beliefs.

"Spice and Wolf": Deity of the Harvest

"Spice and Wolf" features a harvest deity named Holo, who decides to travel with a merchant named Kraft Lawrence. While the mythology depicted in this anime isn't purely Japanese, many elements and motifs reflect traditional beliefs in deities and nature spirits that are prevalent in Japanese culture.

"InuYasha": A Half-Demon in Medieval Japan

"InuYasha," an anime created by Rumiko Takahashi, centers on the adventures of Kagome, a girl from modern-day Tokyo, who is transported to medieval Japan. There, she meets a half-demon named InuYasha, and together they search for the shards of the shattered Shikon jewel. Throughout the series, numerous characters and motifs from Japanese mythology emerge, from demons to deities.

"Princess Mononoke": Man's Struggle with Nature

One of Hayao Miyazaki's most renowned works, "Princess Mononoke," focuses on the conflict between humans and the gods of the forest. The main character, Ashitaka, attempts to mediate the conflict between humans and the gods, including the titular character, San, who lives amongst wolves. The film is a profound reflection on humanity's relationship with nature, showcasing both the beauty and the terror of the mythological world.

"Shinsekai Yori": The Legend of a New World's Creation

"Shinsekai Yori": The Legend of a New World's Creation

Though "Shinsekai Yori" has a dystopian atmosphere, it draws inspiration from elements of Japanese mythology, especially the concept of a new world and its creation. It presents a vision of a society where humans develop telekinetic abilities, and mythology becomes a way to explain and control these abilities within the culture.

Echo of Myths: Reflections and Significance

Japanese mythology is like a mosaic made up of vibrant, profound stories full of cultural richness, reflecting the values, fears, and dreams of the island's people. By analyzing these tales, one can better understand not only Japan's historical and cultural contexts but also the universal aspirations of humanity that manifest in these legends. In many cultures worldwide, similar themes about creation, deities, and man's relationship with the world around him appear. This reminds us of the universality of certain values and thoughts that connect people regardless of their origin, while simultaneously highlighting the uniqueness and richness of each individual tradition.

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

According to Japanese mythology, following the birth of the primary deities came the inception of the first lands. Central to this process were Izanagi and Izanami, siblings and concurrently, a couple, who were entrusted with a celestial jewel and a spear by elder deities. When they swung this spear over the primordial ocean, droplets falling off it created Japan's first island – Onogoro. It was on this island that the romantic unions between Izanagi and Izanami became the foundation for the birth of numerous other deities and kami, as well as the archipelago itself.

According to Japanese mythology, following the birth of the primary deities came the inception of the first lands. Central to this process were Izanagi and Izanami, siblings and concurrently, a couple, who were entrusted with a celestial jewel and a spear by elder deities. When they swung this spear over the primordial ocean, droplets falling off it created Japan's first island – Onogoro. It was on this island that the romantic unions between Izanagi and Izanami became the foundation for the birth of numerous other deities and kami, as well as the archipelago itself. Amaterasu: The Light that Leads the Nation

Amaterasu: The Light that Leads the Nation  Susano'o: Unpredictability and Transformation

Susano'o: Unpredictability and Transformation  "Kamisama Kiss": Romantic Entanglements with Kami

"Kamisama Kiss": Romantic Entanglements with Kami  "Shinsekai Yori": The Legend of a New World's Creation

"Shinsekai Yori": The Legend of a New World's Creation