Demon Namahage: A Dark Presence on New Year's

"泣く子はいねがぁ?怠け者はいねがぁ?"

(Naku ko wa inegā? Namakemono wa inegā?)

"Are there any crying children here? Are there any slackers here?"

- Namahage, New Year

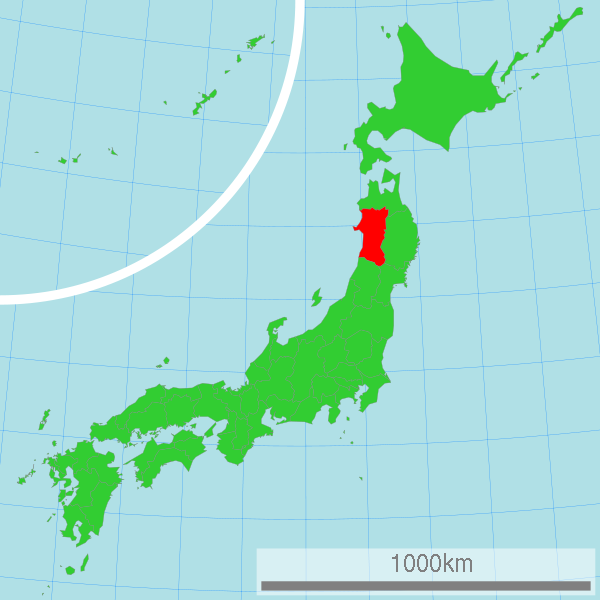

Akita, a remote prefecture in the northwest of Honshu, is known for its dense forests, harsh winters, mountainous areas, and beautiful coast along the Sea of Japan. Here, where winter snow transforms the landscape into a white, almost fairy-tale world and low temperatures give the air a crystal-clear quality, some of the more enigmatic and darker traditions of Japan are cultivated. Akita, though modern and dynamic, maintains a deep respect for its cultural heritage, of which Namahage is the most significant symbol. Amidst frozen lakes, snow-covered roofs of traditional houses, and frosty air that cuts to the bone, Namahage stand as living relics of the past, a mystical bridge connecting ancient beliefs with modernity.

In Japanese culture, Namahage act as strict teachers. Their visits are a test for residents – checking whether children have been obedient, or if household members have worked hard over the past year. They are characters both terrifying and revered, bringing warnings but also promises of protection and prosperity. Namahage are a manifestation of Japanese philosophy, where respect for tradition and social discipline is as important as the joy of living.

Who are the Namahage?

Who are the Namahage?

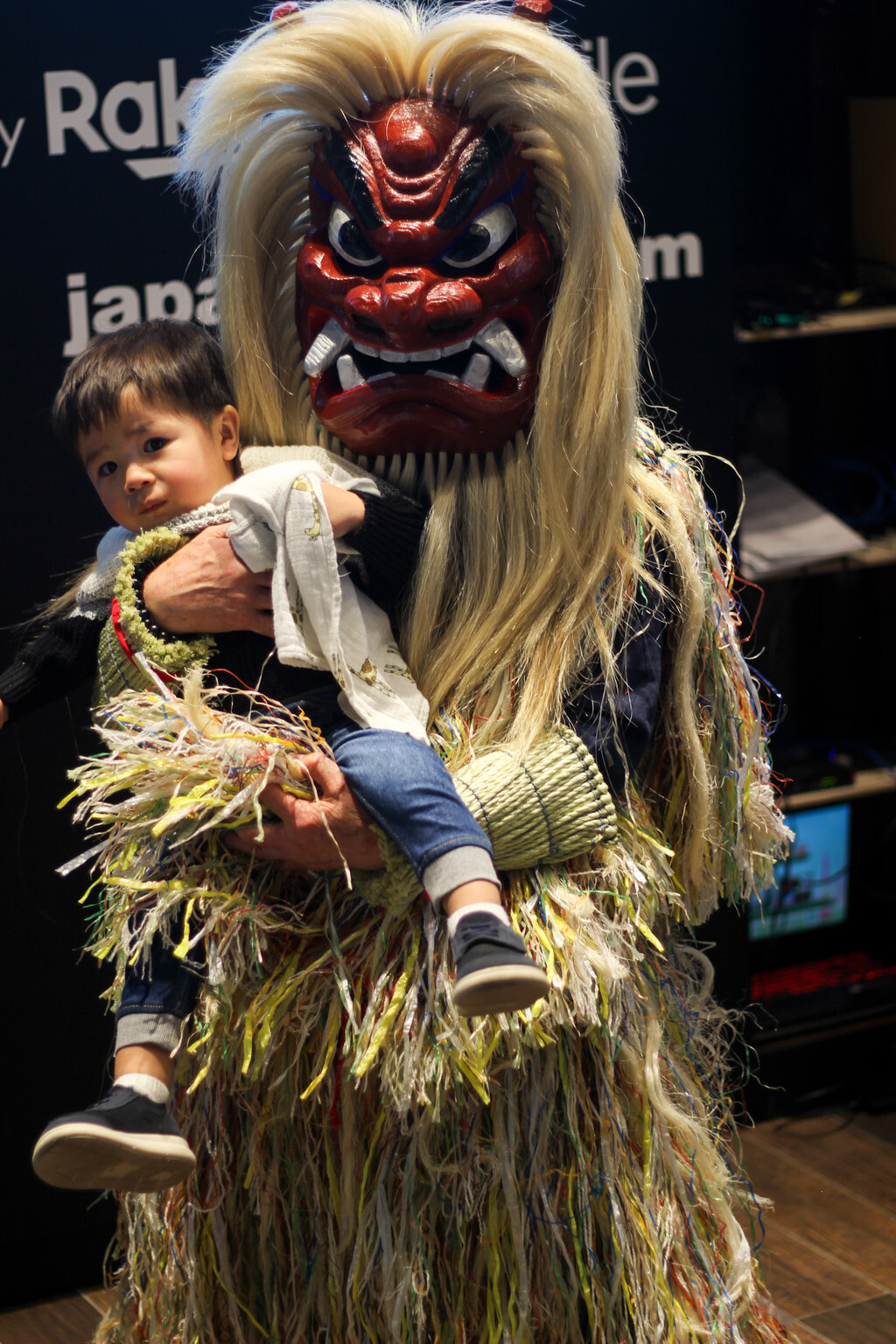

Namahage are oni demons straight out of nightmares. Their appearance is meant to be terrifying – they have huge demonic faces (those famous masks), with distinct, angry features and sometimes horns. Their attire consists of heavy, frayed straw coats that rustle and crackle with every movement. They carry knives or other bladed weapons in their hands. Their postures are dominant and intimidating, and as they traverse the snowy streets of Akita, they evoke images of a demon invasion.

Namahage instill fear not only with their appearance but also with their behavior. Their ritual of visiting homes during New Year's celebrations is both theatrical and terrifying. They enter homes with a loud roar, asking: "Are there any lazy children here?", "Has anyone neglected their duties?". Their presence is a warning – they encourage hard work and obedience and remind of the consequences of laziness and disobedience. Although they do not inflict physical harm, their symbolic threats and dramatic gestures linger long in the memory.

Over time, the word "namahage" evolved, acquiring a richer cultural and symbolic meaning. Nowadays, "removing blisters" by Namahage is seen as a New Year's ritual, intended to encourage hard work and get rid of "blisters" of laziness. Interestingly, Namahage is also associated with the word "namakemono", meaning a lazy person, further emphasizing the symbolic meaning of combating idleness and promoting hard work.

History and Evolution of Namahage

Over time, the figures of Namahage evolved in folklore, becoming more complex and multidimensional. Initially, they may have been perceived as frightening and strict, but over time they gained the status of community guardians. Their role transformed from mythical guardians of morality into cultural icons that serve as a reminder of the importance of tradition, family, and social cooperation.

The perception of Namahage has significantly changed over the centuries. Modern Japanese society sees in Namahage less of a threat and more of a cultural heritage and an important part of local identity. Namahage festivals, such as the famous Namahage Sedo Matsuri, have become important cultural events, attracting both residents and tourists eager to experience this unique aspect of Japanese culture.

Evolution of the Image

Evolution of the Image

Namahage in Japanese history present a fascinating example of how ancient beliefs and traditions can be transformed and adapted over the centuries. One of the most well-known aspects of Namahage is their connection with the "999 Steps" legend. This story tells of demons that were supposed to build a thousand steps to a temple at the top of a mountain in one night. When they were close to completing the task, the villagers tricked them by imitating the crowing of a rooster to announce a false sunrise. The demons, thinking dawn had come, abandoned their task at 999 steps and retreated to the mountains forever, leaving the stairs unfinished. According to this story, the demons, which failed to complete their task, were transformed into the figures of Namahage. They became symbolic guardians who return to the villages every year to remind the inhabitants of the consequences of laziness and the importance of hard work.

Another interesting story is that according to which Namahage had their beginnings as people from other countries who arrived on the shores of the Oga Peninsula. Their incomprehensible language and foreign appearance made the locals consider them as demons. Perhaps they were merchants, explorers, or even castaways from distant regions of Asia or even further corners of the world. Their unusual appearance, different from traditional Japanese dress and physical features, aroused curiosity, but also fear and uncertainty among the local population. Equally foreign and incomprehensible to the residents of Oga was their language. The inability to communicate and unfamiliarity with local customs could lead to misunderstandings and fears. For these reasons, the newcomers were transformed into the figures of Namahage in legend. In Japanese folklore, the transformation into demonic beings often symbolizes not only fear of the unknown but also the process of assimilation and understanding of foreign cultures.

In more recent times, Namahage have been officially recognized as an important element of Japan's intangible cultural heritage. This recognition highlights their significance not only as an element of folklore but as an important part of Japanese cultural identity. Namahage festivals have become popular tourist attractions, attracting people from all over the country, which testifies to their lasting impact on Japanese culture.

Namahage Today

During the Namahage festival, which mainly takes place during the New Year period, men from the local community dress up as Namahage, donning characteristic masks and straw outfits. They traverse the streets and visit homes in their communities, creating an atmosphere of both (theatrical) fear and excitement. Their arrival is a harbinger of important New Year's celebrations, and their task is to remind the residents of the necessity to maintain traditions, hard work, and morality.

During the festival, various shows and games often take place. In some regions, parades are organized in which Namahage march through the city streets, creating a spectacular and unforgettable spectacle. In other places, traditional dances and music shows are held, where Namahage are the main characters. Many of these events are interactive, allowing participants to have direct contact with Namahage figures.

Namahage festivals are not only an important cultural element but also a tourist attraction, attracting visitors from all over Japan and abroad. They are an opportunity to celebrate, but also to reflect on important aspects of Japanese culture and identity.

Namahage in Pop Culture

Namahage, while rooted in tradition, have also found their place in the world of contemporary Japanese pop culture. From manga to movies, these unique characters take on various forms, often retaining their cultural and symbolic weight.

Manga "GeGeGe no Kitaro" (1960, Shigeru Mizuki)

Manga "GeGeGe no Kitaro" (1960, Shigeru Mizuki)

"GeGeGe no Kitaro" is a classic manga by Shigeru Mizuki, where Namahage appear as one of the numerous yokai (spirits). In this story, Namahage serve both terrifying and comical roles, allowing Mizuki to explore the boundaries between folklore and modernity.

Manga "NonNonBa" (1977, Shigeru Mizuki)

In another manga by Mizuki, "NonNonBa", Namahage are portrayed more traditionally. Here we encounter stories from an older woman about yokai, including Namahage, presented as part of Japanese spiritual heritage.

Anime "Summer Wars" (2009, Mamoru Hosoda)

In "Summer Wars" by director Mamoru Hosoda, Namahage are portrayed as an element of a multi-generational story. Here, Namahage are integrated with modern technologies, showing how tradition has survived and adapted to the modern world.

Anime "Hanamaru Kindergarten" (2010, Seiji Mizushima)

In the "Hanamaru Kindergarten" series, Namahage appear in a humorous context. They are used to introduce children to the world of Japanese folklore, showing their more friendly side.

Video Game "Ōkami" (2006, Clover Studio)

In the game "Ōkami," Namahage appear as adversaries. Their appearance and behavior align with traditional descriptions, allowing players to directly confront these legendary figures.

Video Game: "Yo-Kai Watch" (2013, Level-5)

Video Game: "Yo-Kai Watch" (2013, Level-5)

In "Yo-Kai Watch," Namahage is one of the many spirits that players can encounter and collect. Here, Namahage are presented in a more playful and approachable manner, encouraging younger players to explore Japanese folklore.

Video Game "Persona" (Series, Atlus)

In the "Persona" series by Atlus, Namahage appear as one of the many mythological characters that players can fight or recruit. Here, Namahage are part of a rich world where various elements of culture and mythology are interwoven.

Video Game "Nioh" (2017, Team Ninja)

Video Game "Nioh" (2017, Team Ninja)

Set in a stylized version of feudal Japan, "Nioh" features Namahage as adversaries. They are depicted as powerful, menacing entities that add elements of Japanese horror and folklore to the game.

Video Game "The Legend of Zelda" (Series, Nintendo)

In the "The Legend of Zelda" series by Nintendo, characters inspired by Namahage may appear in various installments as mysterious and sometimes terrifying figures. Their presence adds an element of mystery and depth to the rich, fantastical world of the game, drawing from the rich palette of Japanese folklore.

Video Game "Onimusha" (Series, Capcom)

In the "Onimusha" series by Capcom, set in feudal Japan, Namahage appear as demonic beings. Players fight against them in the context of a broader story about samurais and supernatural forces, adding a unique atmosphere and immersion in traditional Japanese horror.

Video Game "Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice" (2019, FromSoftware)

In "Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice" by FromSoftware, characters and motifs inspired by Namahage are present. This game, a blend of Japanese mythology and history, uses elements of folklore, including Namahage, to create a unique and challenging experience for players embodying a shinobi in a fantastical version of the Sengoku Jidai in Japan.

Namahage: Guardians of Tradition in Modern Japan

Namahage: Guardians of Tradition in Modern Japan

Over centuries, Namahage have not only preserved their important role in Japanese culture but have also become a significant symbol in modern Japan. Their presence in festivals, art, and media attests to the remarkable adaptability of this motif. Today, Namahage represent more than just fear of old ghosts; they symbolize the endurance and immutability of values that are key to Japanese identity.

Namahage also play a significant role in education and transmitting values across generations. In schools and media, Namahage are often used as a tool for teaching about the history and culture of the region. Taking various forms – from terrifying characters in video games to inspiring figures in movies, to art objects – Namahage continue to inspire and fascinate. Their evolution from folkloric ghosts to a cultural symbol shows how tradition can be dynamic and survive, adapting to a changing world.

>>SEE ALSO SIMILAR TOPICS:

Shintoism at the Heart of Manga and Anime: The Profound Mark of Tradition in Japanese Pop Culture

Kachi-kachi Yama: The Rabbit vs Tanuki, A Tale of Murder and Torture

Kojiki & Nihon Shoki: Ancient Tales in Contemporary Echoes

Japanese Folklore in Shin Megami Tensei: Playing Persona in the Rhythms of Shinto

Hokkaido Before the Japanese: The History and Culture of the Ainu

Yōkai and Kami: A Bestiary of Mythological Creatures of Japan in Anime

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Who are the Namahage?

Who are the Namahage?

Evolution of the Image

Evolution of the Image Manga "GeGeGe no Kitaro" (1960, Shigeru Mizuki)

Manga "GeGeGe no Kitaro" (1960, Shigeru Mizuki) Video Game: "Yo-Kai Watch" (2013, Level-5)

Video Game: "Yo-Kai Watch" (2013, Level-5) Video Game "Nioh" (2017, Team Ninja)

Video Game "Nioh" (2017, Team Ninja) Namahage: Guardians of Tradition in Modern Japan

Namahage: Guardians of Tradition in Modern Japan