A Dictionary of Delights – 15 Japanese Words for Fleeting Moments Worth Remembering

Learning Mindfulness

Words as Windows of Perception

Linguists have long observed that language is not merely a tool of communication but also a way of shaping the very world we see. The Sapir–Whorf hypothesis proposes that the structure of a language influences our perception of reality — that what we can name becomes sharper, closer, more significant. Ludwig Wittgenstein expressed it even more simply: “The limits of my language are the limits of my world.” One might take this quite literally — what we cannot describe easily slips past the gaze of our awareness.

Learning new words, then, is also a kind of learning new phenomena, new sensations, new worlds. What was once indistinct suddenly takes shape; what seemed accidental reveals itself as recurring; what was ordinary becomes marked, named, and remembered. Such is the power of the words we are about to encounter. These fifteen Japanese terms describe fleeting natural wonders we all know — and yet we often fail to notice them, or glimpse them only for an instant, because what remains unnamed so easily dissolves from memory. These words do more than teach us something about the Japanese language; they open windows of perception. They allow us to see more, feel more deeply, and recognize what was once invisible.

Why Do the Japanese Have So Many Words for Fleeting Natural Phenomena?

The first is the concept of mono no aware (物の哀れ), coined by the 18th-century scholar Motoori Norinaga. While studying Murasaki Shikibu’s Genji monogatari, Norinaga described mono no aware as “a deep stirring of the heart brought about by the awareness of impermanence.” It is a sensitivity to beauty that exists precisely because it is fragile and transient. When the first petal of a cherry blossom falls, we feel both sorrow and wonder — two feelings that cannot be separated. From this sensibility arise words like 花曇り (hanagumori) — “a cloudy day during cherry blossom season” — or 風花 (kazahana) — “snowflakes dancing in sunlight.”

- “The east wind carries the first scents of plum blossoms” (東風解凍, tōfū kaetō),

- “Frogs begin to sing” (蛙始鳴, kawazu hajimete naku),

- “The wind dries the dew upon bamboo leaves” (竹露解乾, taketsuyu hodoku kanaru).

Through this arose a language of micro-observation, training the eye to notice even changes so delicate that the West rarely named or even perceived them.

(More on the seventy-two seasons of the Japanese calendar can be found here: The 72 Japanese Seasons, Part 1 – Spring and Summer in the Calendar of Subtle Mindfulness and here: 72 Japanese Micro-Seasons, Part 2 – Autumn and Winter in the Calendar of Conscious Living).

And so the Japanese language abundantly names what elsewhere remains nameless. Each of these words is like a magnifying glass turned upon a fragment of the world, revealing nuances invisible without the knowledge of their names. Through them, the moon, the rain, the wind, the mist, and the light cease to be mere background — they become events, moments worth noticing.

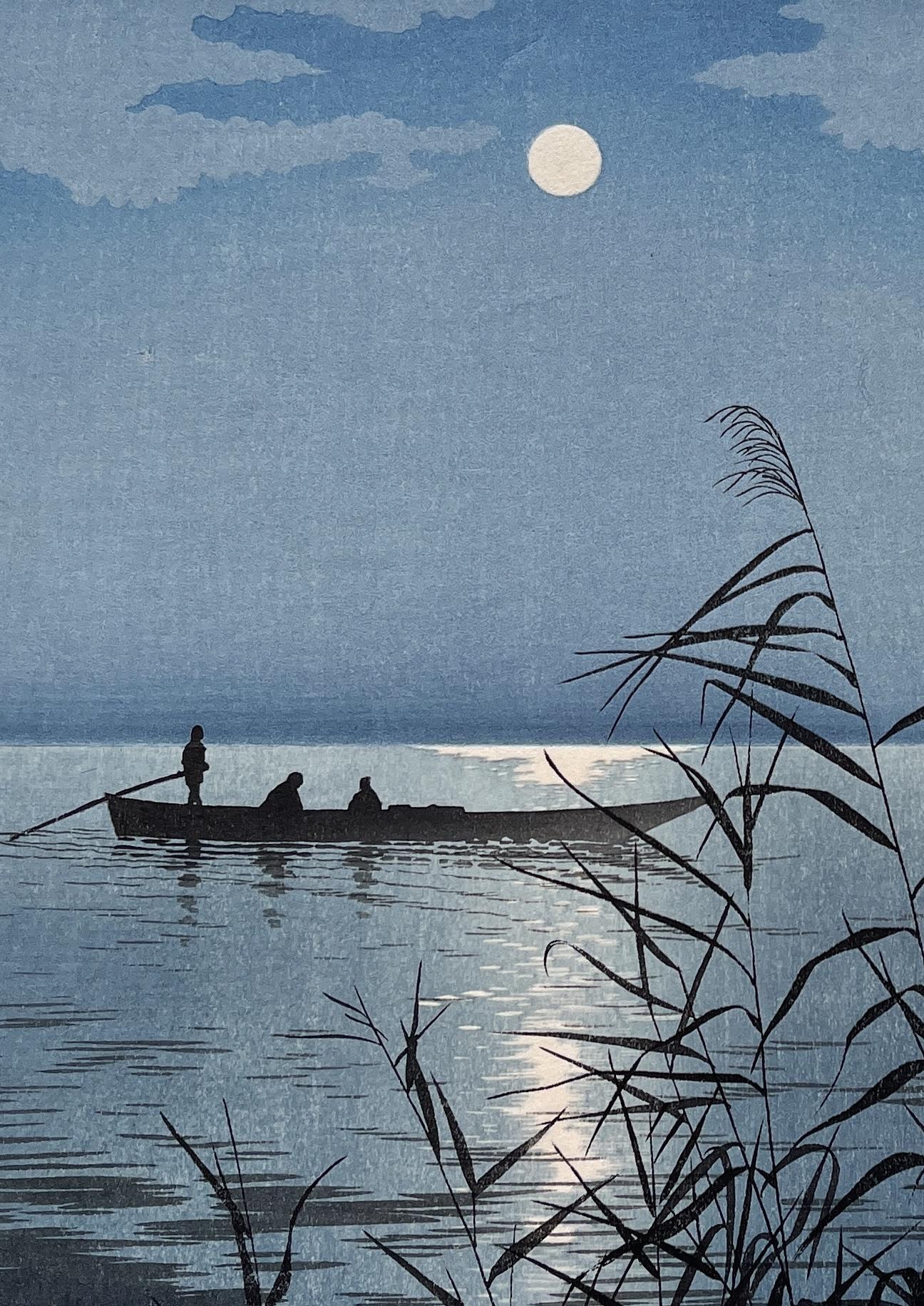

川明かり

(kawaakari)

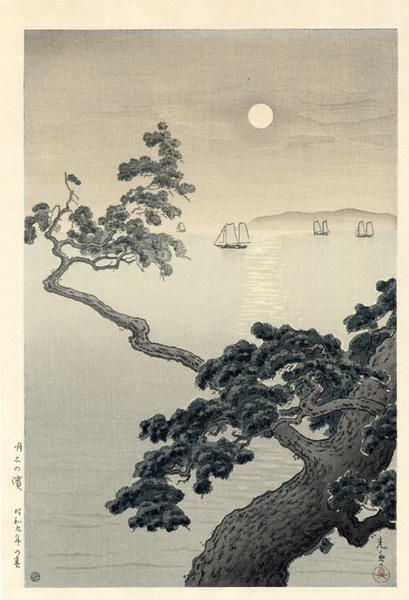

The reflection of moonlight (or lanterns) on the surface of a river at night

Kawaakari appears frequently in haiku, especially in poems from the Edo period, where it was often associated with scenes from summer night festivals along rivers such as the Sumida or Kamogawa. In ukiyo-e painting, this motif recurs often — for instance, in Hiroshige’s series “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo”, where nocturnal riverscapes are captured with exquisite sensitivity to light. Even today, the term is widely used in Japan when describing landscapes, and some riverside hotels and restaurants consciously advertise “the most beautiful kawaakari in Kyoto” as an aesthetic experience in itself.

木漏れ日

(komorebi)

Sunlight filtering through the leaves of a tree canopy, flickering as the wind stirs the branches

The word 木漏れ日 is formed from three characters: 木 (ki) — “tree,” 漏れ (more) — “to leak” or “to filter through,” and 日 (hi) — “sun” or “daylight.” Together, they create the image of “sunlight leaking through trees.” What makes this term so beautiful is the inherent dynamism: light here is not treated as static but alive, moving, changing. Unlike many European languages, which focus on “shade” or “shadow,” Japanese gives shape to the motion of light itself.

Komorebi is among the most frequently described phenomena in haiku poetry. In the works of Matsuo Bashō, it appears repeatedly, where sunlight between leaves symbolizes both transience and fleeting harmony. Within the aesthetics of wabi-sabi, we find the same sensibility: beauty lies in what is ephemeral, ever-shifting, impossible to hold. Today, komorebi has become a beloved motif in photography and cinema, particularly in Studio Ghibli films, where sunlight filtering through trees often plays a subtle yet powerful role in shaping atmosphere and emotion.

夕凪

(yūnagi)

The evening calm on the sea, when after sunset the wind ceases and the water becomes as smooth as glass

The word 夕凪 consists of two characters: 夕 (yū) — “evening,” and 凪 (nagi) — “calm on the sea” or “a lull in the wind.” Interestingly, the character 凪 is unique to Japanese; it does not appear in Chinese writing. It was created specifically to name this phenomenon observed along the Seto Inland Sea, where fishermen experienced this sudden evening stillness daily. Today, nagi is also used metaphorically — for example, in the phrase 心の凪 (kokoro no nagi), meaning “a calm sea within the heart,” an inner stillness of the soul.

Yūnagi frequently appears in travel journals (kikōbun) from the Edo period, where writers recorded their impressions of journeys among Japan’s islands. In modern literature, the term was often used by authors such as Shiga Naoya, a master of subtle atmospheres. In ukiyo-e painting, the motif can be seen in Hiroshige’s seascapes, especially within series depicting Edo Bay. Even today, the word yūnagi remains alive and widely used, particularly in coastal regions where people still witness this daily rhythm of nature.

時雨

(shigure)

A light, fleeting rain of late autumn or early winter, heralding the arrival of cold

Shigure is one of the most frequently occurring kigo in classical waka and haiku poetry. In the Manyōshū of the 8th century, it appears in contexts of longing and solitude. Matsuo Bashō, the master of haiku, used the word repeatedly, for instance:

初時雨猿も小蓑をほしげ也

(hatsu-shigure saru mo komino wo hoshige nari)

“The first autumn rain —

even the monkey

seems to long for a straw raincoat.”

The motif of shigure also threads through visual art. In Hiroshige’s landscapes from series such as “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo” and “The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō”, delicate diagonal lines of rain evoke a mood of passing melancholy, capturing moments poised between seasons and between emotions.

風花

(kazahana)

Snowflakes swirling in the air beneath a blue sky, when the sun shines despite winter

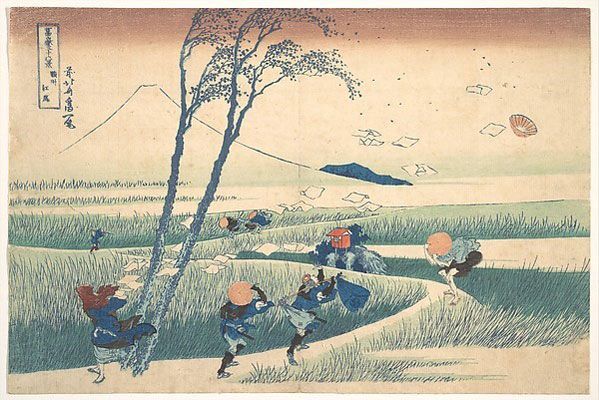

Kazahana often appears in classical literature — for example, in haiku collections by Issa and Buson — where sun and snow are contrasted as two elements coexisting in a single moment. It is also a popular motif within the aesthetics of wabi-sabi, where beauty resides in unexpected, ephemeral encounters. In ukiyo-e art, Hiroshige depicted kazahana in his winter views of Edo, creating a contrast between the bright sky and the dancing flecks of white (for instance, in “Asakusa Kinryūzan” in One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

花曇り

(hanagumori)

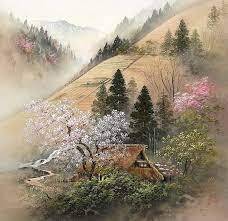

A lightly overcast day in the height of cherry-blossom season

花曇り combines 花 (hana) — “flower” (in this context it almost always means cherries; read also about hanami: Hanami – April Day of Reflection on What You Have Now, Which Will Pass and Not Return) and 曇り (kumori) — “cloudiness” or “overcast.” Together they form, quite literally, “clouded flowers” or “an overcast day of blossoms.” The word has a very precise application: it is not used for other trees or seasons — it is inseparable from the short, intense period of hanami.

In classical poetry, hanagumori symbolizes joy that is already passing. In the very midst of happiness comes a sudden awareness — that this is the apex, that from now on the joy will only wane, that it is already slipping away — and that is precisely the meaning of hanagumori. In the Kokin Wakashū of the 10th century there is a poem that describes an overcast April day as a metaphor for love in full bloom, which too will soon fade. In ukiyo-e painting, Hokusai and Hiroshige often portrayed cherry trees against a soft, milky sky, creating a contemplative mood. Today the word is still used in weather forecasts, especially during the sakura season, and it retains its poetic connotations.

静寂

(seijaku)

The silence of profound stillness and complete suspension in immobility

The word 静寂 consists of two characters: 静 (sei) — “calm,” “unmoving,” and 寂 (jaku) — “lonely,” “empty,” but also “imbued with quietude.” Interestingly, 寂 also appears in the term 寂寞 (sekibaku), used in classical Chinese poetry to describe a melancholic quiet. In Japanese, seijaku thus denotes not only the absence of noise but a state of inner harmony — the quiet of the soul and the surroundings at once.

The concept of seijaku is one of the pillars of Zen aesthetics and often appears in treatises on the tea ceremony, such as the Nanpōroku attributed to Sen no Rikyū. In sumi-e painting, silence was conveyed through expanses of untouched ink (read more about sumi-e: Spiritual Landscapes in Japanese Sumi-e Art), and in Zen gardens through the arrangement of stones, gravel, and moss (on karesansui gardens: Japanese Karesansui Garden is a Mirror in Which You Can See Yourself). Bashō wrote of this quality in his famous haiku:

閑さや岩にしみ入る蝉の声

shizukesa ya iwa ni shimiiru semi no koe

“Silence…

until into the rocks

the song of cicadas sinks.”

In contemporary usage, seijaku has become a key term in Japanese design, especially in minimalist architecture — it describes the atmosphere of a space where quietude becomes an aesthetic experience.

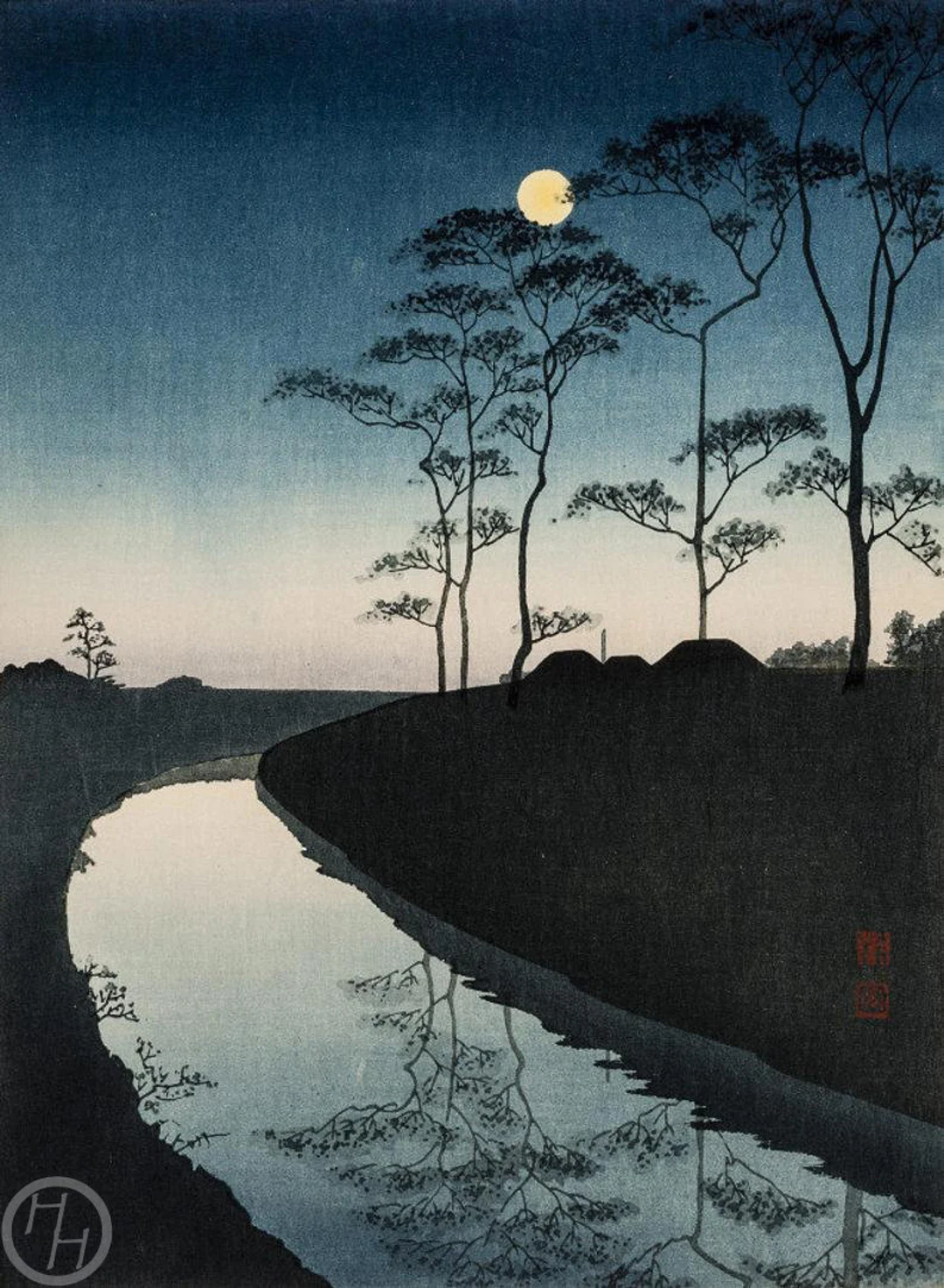

朧月夜

(oborozukiyo)

A spring night with the moon lightly veiled, when its light mingles with mist and moisture

The word 朧月夜 consists of three characters: 朧 (oboro) — “misty,” “blurred,” 月 (tsuki) — “moon,” and 夜 (yo) — “night.” Literally, it means “a night of a hazy moon.” In classical Japanese, oboro was used exclusively to describe light phenomena obscured by moisture, not mist itself. It is a subtle distinction: the focus is not on the obstacle, but on how light diffuses within it.

“Oborozukiyo” is also the title of a famous song written in 1914 by the poet Takamura Kōtarō, with music composed by Taki Rentarō. The piece became a classic of Japanese school songs and is still performed during spring ceremonies. The phenomenon appears as well in Heian literature, for example in Genji monogatari, where nocturnal landscapes of a blurred moon symbolize the transience of love and longing. In Yoshitoshi’s ukiyo-e from the series “One Hundred Aspects of the Moon" , we find many works in which the moon’s soft, hazy light lends scenes an oneiric mood — spirits, goddesses, and samurai are portrayed in half-shadow, as though they drifted in a world between waking and dream.

山笑う

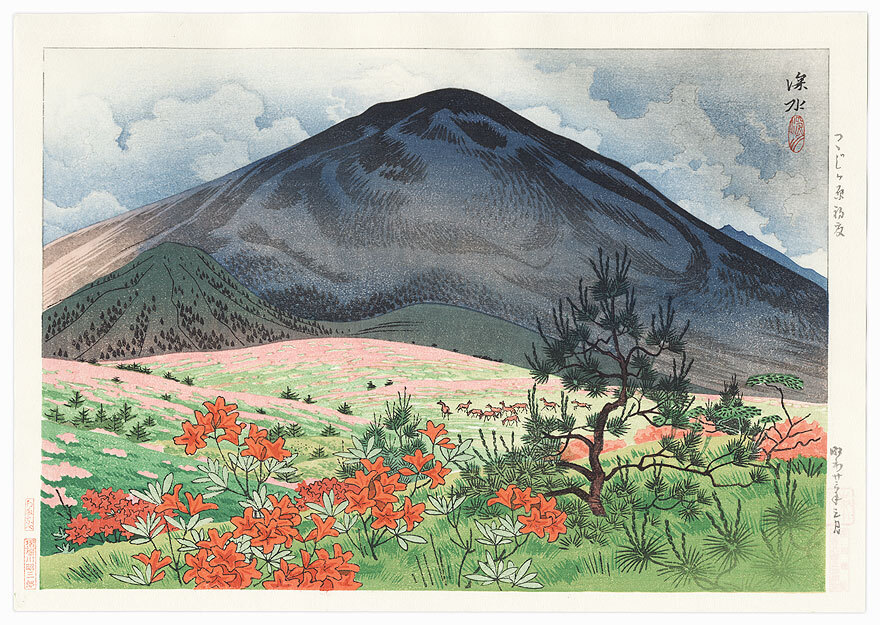

(yama warau)

“Laughing mountains” — a description of the lush colors of spring, when fresh greenery spreads across the slopes

The term 山笑う consists of two characters: 山 (yama) — “mountain,” and 笑う (warau) — “to laugh” or “to smile.” It is a metaphorical expression that first appeared in classical Chinese poetry, particularly in Su Shi’s (蘇軾) “Poem of the Four Seasons.” In Japan, the expression was adopted during the Heian period and is still used today in literature and poetic calendars as a spring kigo.

The motif of “laughing mountains” is popular in both landscape painting and literature. In Hiroshige’s ukiyo-e prints, spring views of Edo often depict hills covered with young greenery, “smiling” beneath pastel skies. In classical haiku, yama warau functions as a kigo, conjuring an image of mountains bursting with vibrant color and life. Today, the expression is sometimes used in the names of inns, hotels, and botanical gardens, chosen to evoke a lively, colorful spring atmosphere.

涼風

(ryōfū)

A cool, refreshing evening breeze in summer

Ryōfū appears in haiku and waka, where its meaning is always double-layered: the joy of relief after sweltering days mingles with a faint sorrow that summer is slipping away. In Hiroshige’s classical ukiyo-e landscapes — especially his nocturnal views of Edo — one can almost “feel” ryōfū: it stirs in the swaying willow branches, flickers in the lanterns strung above the Sumida River, and quiets the people seated along the embankments. Today the term still appears occasionally in weather forecasts, but in everyday language it retains an aesthetic nuance — describing a breeze that soothes while also carrying a sense of transition.

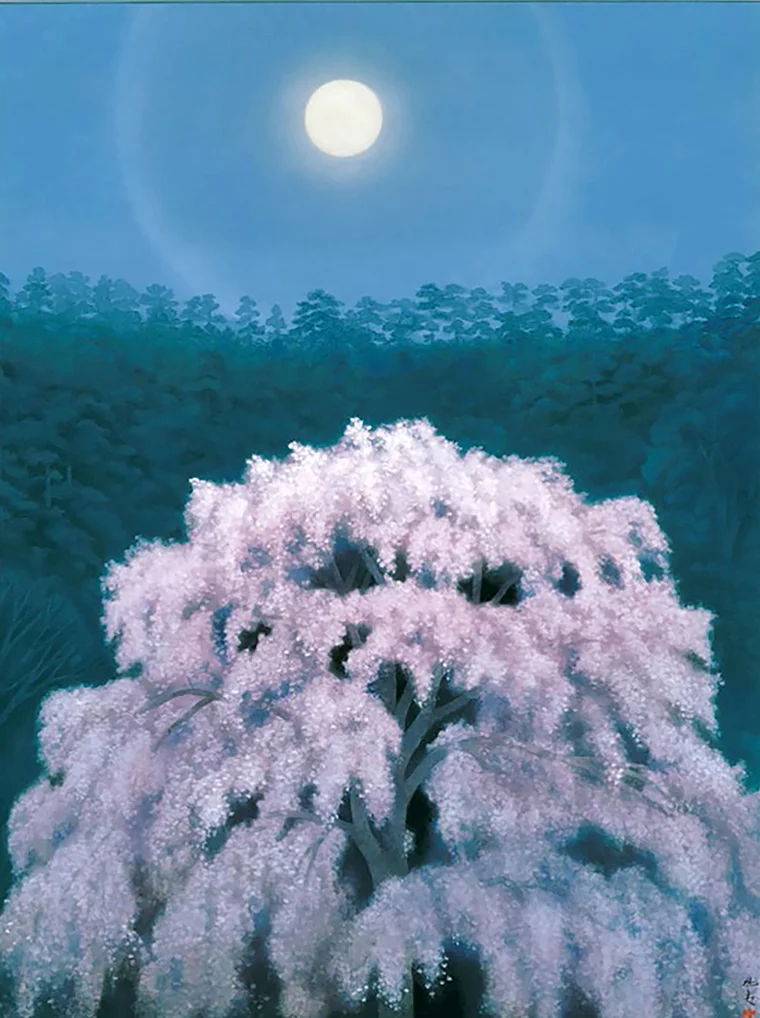

花明かり

(hanaakari)

The soft glow of cherry blossoms reflecting moonlight in a rosy haze

The word 花明かり is composed of two characters: 花 (hana) — “flower” (implicitly referring to cherry blossoms), and 明かり (akari) — “glow,” “light.” Together they create the image of flowers that shine — not with their own light, but with moonlight reflected from their petals. It is a profoundly poetic expression, uniting in a single word the experiences of light, night, spring, and the fleeting beauty of sakura.

The motif of hanaakari appears in many classical waka and haiku, where it symbolizes impermanence and passing beauty. In the Kokin Wakashū, one finds poems describing moonlit nights when blossoms and light merge into a single experience of longing, love, and transience. Many woodblock artists — especially Hiroshige — depicted night-time hanami illuminated by lanterns, but in some ukiyo-e prints one can sense the subtle essence of hanaakari, where petals seem to glow softly with reflected light. Today the term is rarely used in everyday speech, but it retains its poetic charm, appearing in the names of restaurants, inns, and traditional hanami festivals.

雪見

(yukimi)

“Snow-viewing” — the traditional contemplation of winter landscapes in Japan

The word 雪見 is made of two characters: 雪 (yuki) — “snow,” and 見 (mi) — “to look,” “to view.” Literally, it means “snow-viewing.” Yet within Japanese culture, the word carries a deeper resonance: it is not about passive observation but about contemplating snow, experiencing its quiet beauty with all the senses.

朝露

(asatsuyu)

Morning dew shimmering upon leaves and grass

Asatsuyu are those delicate, glistening droplets that settle upon blades of grass, leaves, and spiderwebs at dawn. In the rising sun they sparkle like scattered pearls, trembling with every breath of air until they vanish, absorbed into the earth. It is among the most ephemeral of natural phenomena — lasting only a few moments before the first warmth of day. In Japan, asatsuyu has long symbolized the fragility of existence and the fleeting nature of moments, making it one of the most frequent images in classical poetry.

The word 朝露 consists of two characters: 朝 (asa) — “morning,” and 露 (tsuyu) — “dew.” Literally, it means “morning dew.” The character 露 carries particular significance — in Japanese poetry since the Heian era, dew has symbolized the impermanence of life, likened to a brief presence in the world that disappears with the first touch of sunlight.

Asatsuyu appears as early as the 8th-century anthology Manyōshū, where dew is described as an emblem of passing time. In Murasaki Shikibu’s Genji monogatari, dew often serves as a metaphor for emotions — beautiful, yet transient. Bashō wrote of it in one of his haiku:

朝露や蜘蛛の糸にも命あり

asatsuyu ya / kumo no ito ni mo / inochi ari

“Morning dew —

even upon a spider’s thread

there hides a life.”

波音

(namine)

The sound of waves breaking against the shore, soothing and calming

The sound of waves is a recurring motif throughout Japanese culture. In Heian poetry, for example, in the anthology Kokin Wakashū, waves often symbolize the transience of love and the fleeting nature of emotions. Bashō wrote of the waves many times, as in this haiku:

波の音や児の声交じる秋の暮

nami no oto ya / ko no koe majiru / aki no kure

“The sound of waves —

mingling with the voices of children

at autumn’s close.”

霧雨

(kirisame)

A delicate, misty rain that settles on the skin rather than falling in drops

The motif of kirisame often appears in classical literature and haiku, symbolizing transience and the gentle shifts of time. It creates a mood of subtle suspension between time and space, a pause where the world feels softer, quieter, and momentarily detached from its own edges.

The Art of Contemplation

Japanese culture has cultivated an extraordinary ability to name what is subtle, fleeting, almost invisible. It has learned to speak of silence as though it carries weight; to describe light filtering through leaves as something alive with its own rhythm; to evoke the wind not only as a cooling presence but as a storyteller whispering of a passing summer.

Perhaps this is the lesson we can take. If we learn to listen more carefully, to see more closely, to touch more attentively — we may begin to create our own words for experiences we have not yet named. Perhaps the world will grow richer not because it has changed, but because we will finally see more of it.

Language is not only a tool for description — it is an art of contemplation.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

10 Japanese Proverbs – Inspirations and Lessons Hidden in Ages-Old Characters

10 healthy things we can learn from the Japanese and incorporate into our own lives

On Japanese Honesty: 10 Vignettes from Everyday Life in Japan, Left Without Comment

Goshin "Guardian of the Spirit" – Bonsai as a Forest in a Pot Telling of Life, Family, and Nature

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!