The Lonely House on Adachi Moor: A Few Seconds Before the Crime in Yoshitoshi’s Psychological Ukiyo-e

That silent moon...

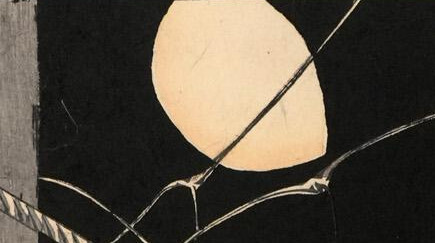

Behind this image, part of the "One Hundred Aspects of the Moon" series, lies a dark legend from the Heian period about the lonely house on the moors of Adachi-ga-hara and the woman who, in desperation, abandoned her humanity. Today, we will delve into this legend and, armed with this knowledge, immerse ourselves in Yoshitoshi’s artwork to understand how art can capture the invisible—the battle of conscience against determination, or more naively: the fight between good and evil. Ahead lies a journey into the psyche of Iwate, into the heart of her tragedy and downfall. And above it all, the moon will watch impassively—its glow illuminating the scene of the tragedy but failing to dispel the darkness that surrounds the protagonist. It is as indifferent as nature itself is to the fleeting passions, sufferings, or crimes of humankind.

Let’s take a closer look...

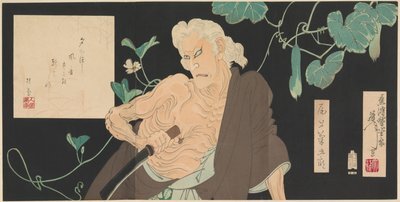

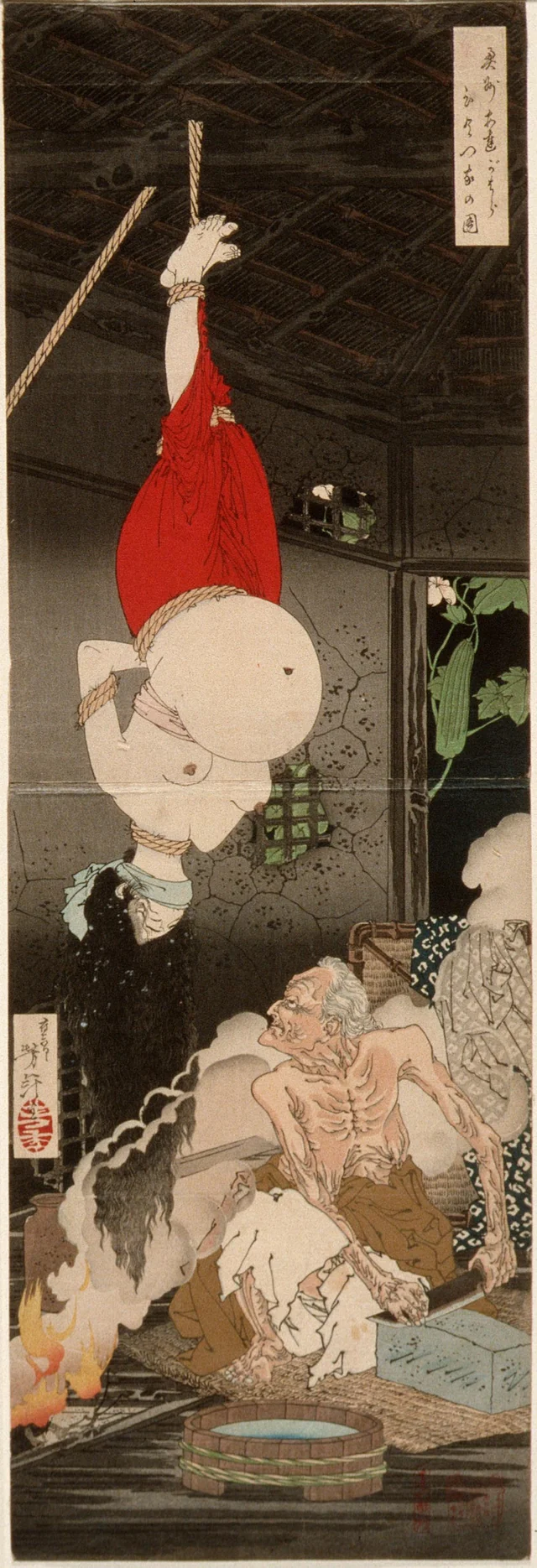

"Moon over a Lonely House on Adachi Moor"

一つ家の月

- Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (月岡芳年), 1886

100 Aspects of Moon (Tsuki Hyakushi, 月百姿)

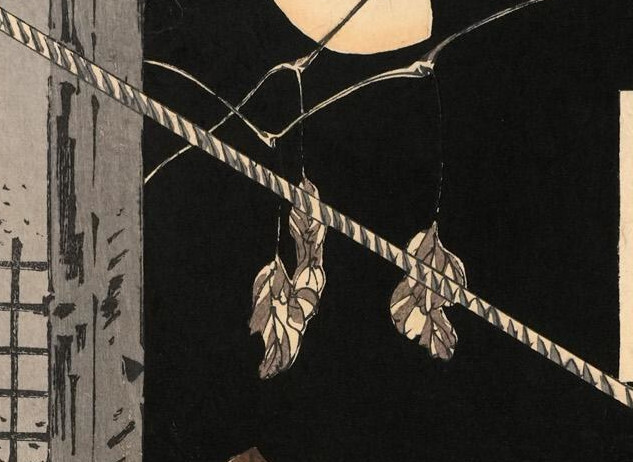

In the background, the winding vines of vegetation seem to have a life of their own, as if they want to engulf the hut. They are like the hands of nature attempting to restore harmony to a place filled with chaos and crime.

The spatial layout of the work seems simple but is filled with subtle contrasts and symbolic shifts. The figure of the old woman occupies the central part of the composition, her movement directed toward the interior of the hut. The viewer feels like an observer of this scene, disturbed by what the woman might soon see, hidden from their gaze. Yoshitoshi deliberately avoids filling the background with details, allowing shadows and emptiness to create a sense of loneliness. This emptiness simultaneously emphasizes how small the old woman is compared to the world around her.

The entire painting is composed so that what is most important remains unseen by the viewer. The crucial moment of tension occurs outside the frame, in the space toward which the old woman moves with her torch. Yoshitoshi masterfully builds an atmosphere of dread and mystery precisely through this absence—what we cannot see seems more terrifying than any creature that could have been depicted. The viewer is left with a sense of unease, wondering what lies beyond the wall, what the old woman will see, and whether what is hidden there is more monstrous than she herself. It is this uncertainty, the boundary between what is shown and what is implied, that makes the work so extraordinarily suggestive and moving.

To fully understand what Yoshitoshi wishes to convey with this painting, we must first delve into the old legend of the Adachi house and the old woman who lived there...

First, about the Adachi legend…

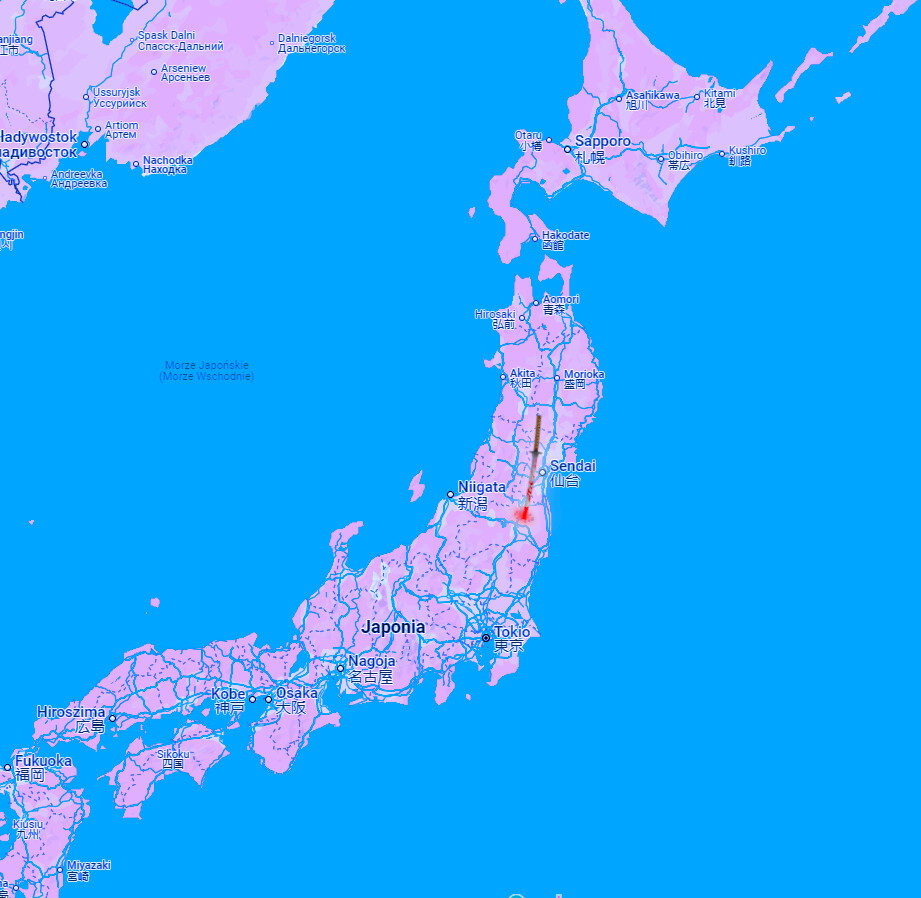

The lonely house on the moors of Adachi (足立) refers to Adachi-ga-hara (足立ヶ原)—the mythical moor (“Adachi plain”), which according to tradition was located in the vicinity of present-day Nihonmatsu in Fukushima Prefecture.

The legend of Adachi-ga-hara has its roots in the Nara period (710–794), when folk tales began to be written down and crystallized as part of Japan’s spiritual culture. Initially, this story was transmitted orally, and its first written accounts appeared in the context of Buddhist religious and moral teachings, which sought to warn people against sins such as murder and betrayal. During the Heian period (794–1185), the legend gained popularity through literary adaptations, and in later eras, it was also featured in Noh theater performances, such as the famous play "Kurozuka" (Black Mound).

So, what does the legend itself say?

The Legend of the Lonely House on the Adachi Moor

She traveled through villages and towns in search of a suitable “candidate”—a pregnant woman who met the onmyōji’s specific requirements. However, her journey lasted far longer than she could have ever imagined. She went from one village to the next, searching for the right woman, but her guilt and inner conflict prevented her from harming anyone. Even when she found a suitable victim, her conscience made her see the face of her beloved daughter in the woman’s features. She could not bring herself to do it—she could not kill...

Iwate’s world came to a standstill. The knife fell from her trembling hands, and the blood in her veins froze like ice. But it was too late. The wound she had inflicted was fatal and irreversible. Her daughter was dying before her eyes, and a grief-stricken Iwate descended into madness.

In the end, the lonely house on the moors of Adachi became a place cursed not only by Iwate’s tragedy but also by the fear of all who knew her story. Travelers avoided the area, having heard tales of screams and wails echoing through the night. It was said that the onibaba, now the embodiment of rage and despair, wandered the moors, hunting unfortunate wayfarers to satisfy her insatiable thirst for blood.

The legend of Adachi-ga-hara endures in Japanese tradition as a dark warning—a story of how loyalty and desperation can lead a person to lose their soul. The lonely hut, the misty plain, and the pale moon that witnessed the tragedy became eternal symbols of the irreversible consequences of human choices.

Now we know what happened at the lonely house on the moors of Adachi-ga-hara—let us return to Yoshitoshi’s painting and look at it once more.

Let us try to understand the painting…

Yoshitoshi draws the viewer deeper into this tragedy through subtle details. The torch in Iwate’s hand casts light on her silhouette but also betrays her intentions. It is both a tool for lighting her path and a symbol of destruction. Her other hand is hidden behind a wall, but we can imagine what it holds—a knife. The moon, the torch, the ropes—each element of the painting contributes to the narrative of inevitable moral downfall.

Yoshitoshi’s choice of this moment is a deliberate artistic move. Instead of depicting violence directly, the artist focuses on psychological tension. Iwate, holding the torch, symbolizes the internal battle—her movements convey determination, but her posture reveals darkness and fear. This is the moment that speaks more about her psychological state than any image of the crime itself could. The painting becomes a study of crime and what transpires in the mind of someone seconds away from committing a heinous act.

Reflections on the painting…

Yoshitoshi’s work is not just an illustration of the legend but also a universal reflection on transience, crime, repentance, and the process of dehumanization brought about by uncontrollable guilt. The figure of Iwate is a metaphor for a person who, in desperation, abandons their humanity, ultimately consumed by a new identity born the moment the knife plunges into the belly of the pregnant woman. The onibaba into which she transforms is not merely a demon—it is the embodiment of the irreversibility of human decisions. From this perspective, her story becomes a parable about the nature of crime and its destructive consequences for the perpetrator. In Yoshitoshi’s world, there is no simple redemption—there is only the cycle of life and death, observed dispassionately by the cold moon high in the sky.

Is Iwate’s transformation into a demon a form of punishment (and if so, by whom?), a tragic release from pain and guilt, or the inevitable result of overwhelming remorse over her actions? Yoshitoshi leaves the viewer in this ambiguity, forcing contemplation of the boundaries of humanity. Iwate becomes a figure of caution—a reminder of how easily one can lose oneself with a single, irreversible decision.

Yoshitoshi’s Legacy

Yoshitoshi’s influence on contemporary artists and Japanese art is undeniable. His ability to blend traditional aesthetics with psychological depth and innovative compositional techniques made him a bridge between the old ukiyo-e art form and modern modes of expression. Contemporary interpretations of his works—in literature, theater, and even pop culture—demonstrate that the themes he addressed remain relevant. Fear, morality, transience—these universal ideas resonate with every generation.

And yet this painting conceals another layer—the inevitable continuity of nature, untouched by human tragedies, crimes, or choices. The mist on the moors, the moon silently observing everything from above, and the vines slowly enveloping the hut on Adachi-ga-hara are symbols of the ceaseless rhythm of life and death beyond our control. In his genius, Yoshitoshi shows that nature does not judge or remember—it simply exists. It is we, humans, who remain forever bound to our actions and their consequences.

>> SEE ALSO SIMIAR ARTICLES:

With Master Hokusai Through Japan's Eight Waterfalls

The Painting "Ghost of Oyuki" – How One Night Three Centuries Ago Began the Yūrei of Modern Horror

The Brilliant Eccentricity of Itō Jakuchū – Discover One of the Eccentric Painters of Edo Japan

Time Stood Still When I Looked at Hiroshige’s “Evening Snow in the Village of Kanbara”

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!